In April 2025, Csaba Szabo participated as session chair at Fostering Accountability for the Integrity of Research Studies (FAIRS), a research integrity meeting in Oxford, which was organised by Dorothy Bishop. This is his conference report, as a guest post.

The FAIRS presentations were published in PDF form on OSF, unfortunately there are no video recordings. I will provide my own opinions on what to foster at the end. Here I would like to briefly mention that I was not invited to speak at the FAIRS meeting. Moreover, although I was previously asked to fill out two long questionnaires as prerequisite for panel participation, I soon understood that any attempt of further contribution from my side would have, uhm, created tensions. Therefore, I chose not to invest money into participating as a guest, not even online.

“Unreliable” by Csaba Szabo – book review and excerpt

Csaba Szabo’s book “Unreliable: Bias, Fraud, and the Reproducibility Crisis in Biomedical Research” – review by Zoltan Ungvari and excerpt.

FAIRS: “Frustrating Attempts at Integrity Reform in Science”

By Csaba Szabo

Between the 7th and 9th of April, Prof. Dorothy Bishop and Prof. Jaideep Pandit (both Fellows of St John’s College, Oxford, UK) organized the FAIRS meeting at their own alma mater. FAIRS, of course, stands for Fostering Accountability for the Integrity of Research Studies –– as opposed to my invention in the title of this report. It attracted about 80 in-person participants and about 120 online attendees. The audience consisted of academic scientists interested in research integrity, journal editors, publisher representatives, university research integrity officers, sleuths, some students, and a few people from the media. The entire program is available on the meeting website.

Dorothy Bishop, of course, is not only a highly accomplished (now-retired) scientist specializing in developmental neuropsychology but also a long-time science integrity warrior. She is probably the most academically accomplished scientist who devotes her time to this extremely important but entirely thankless and immensely frustrating issue. She used to be a Fellow of the Royal Society (until she resigned in protest against the election of Elon Musk into this society – a fascinating story, but one that does not belong in the current article). What does belong, however, is that Dorothy has been doing all the right things for scientific integrity reform for at least the last decade, including sleuthing, blogging, vlogging, tweeting, raising the issue of scientific misconduct and the replication crisis in dozens of interviews, testifying before the UK Parliament, and now, finally, organizing a 3-day meeting.

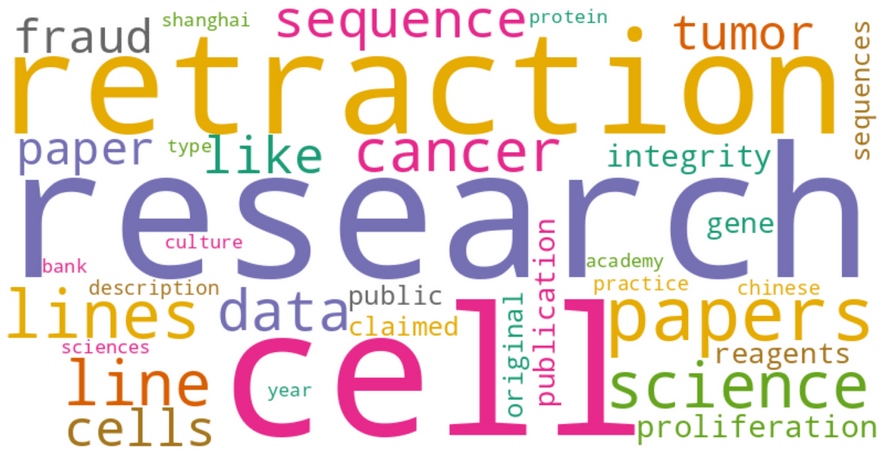

In the spirit of the day, I loaded all presentation PDFs from the meeting into ChatGPT and asked it to extract the most commonly used words to produce a Word Cloud, which can be admired here. (Each word’s font size is proportional to the frequency of the word used in the presentations.) All of these words are, of course, entirely familiar to the readers of For Better Science. Some words that are sorely missing, however, are “reform,” “policy,” “penalties,” “consequences”, and “solutions.” More on that later. First, I will try to summarize the main topics discussed at the meeting.

Preclinical Scientific Misconduct

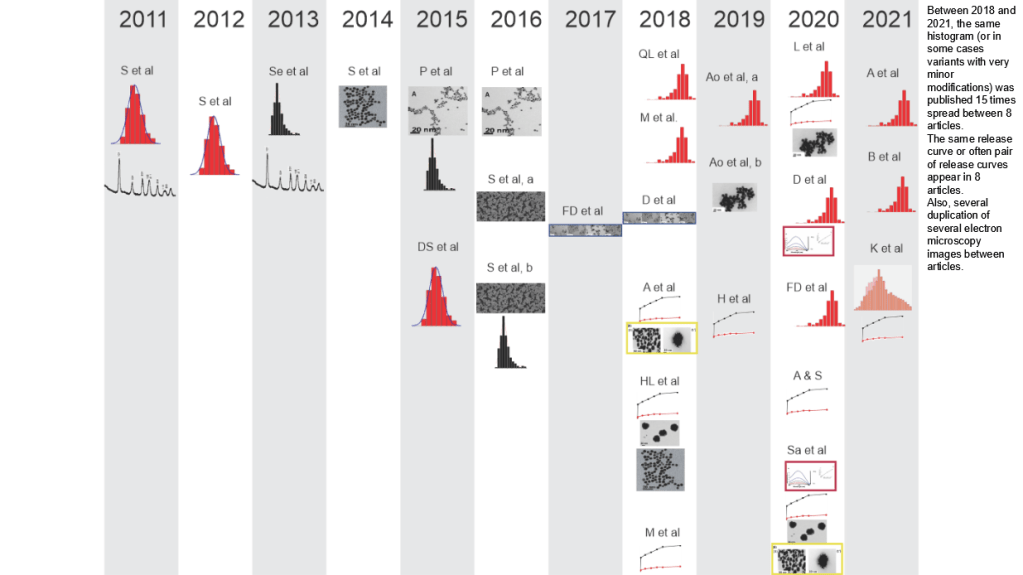

A significant portion of the talks focused on various aspects of scientific misconduct and research integrity, illustrating diverse issues including fraudulent data, problematic peer review, authorship conflicts, plagiarism, and the ethical dimensions of research practices. The topic of data fraud and manipulation was covered by several speakers, including the world’s most prominent expert (and recent Einstein Foundation awardee), Elisabeth Bik. She highlighted the extensive issues of manipulated images and falsified data that For Better Science readers know all too well, emphasizing the problem of extremely slow responses from journals and institutions.

A particularly sobering realization for me occurred when she showed AI-generated histological images that were indistinguishable from real ones. She stated that Western blots can now also be created this way. If this is indeed the case, the usual methods of fraud detection (visual observation, ImageTwin, etc.) will soon become obsolete, and nobody currently knows how AI-generated (i.e., unique) images will be detectable in the future. (At the meeting, there were many discussions and even breakout sessions on how to address the threat of AI; however, I did not hear any solutions beyond broad statements like “we ought to fight AI with AI.”)

Ivan Oransky provided further insights into the mechanisms of retractions and discussed their consequences for researchers, emphasizing that sanctions vary widely, including (usually slight) career penalties and (usually rarely enforced) legal repercussions. He also highlighted how journal practices, citation impact, and university rankings incentivize misconduct, calling for a reassessment of current publishing and ranking systems.

Nick Brown illustrated how statistical tests such as GRIM (Granularity-Related Inconsistency of Means) can detect impossible numerical values indicative of fraudulent research. He and other statistical experts who attended the meeting were adamant that truly random and “life-like” numbers are difficult to fake. They stressed that detailed statistical analysis can detect much fraud and should therefore be performed by journals at the very first step of the evaluation process, i.e., prior to sending the paper to reviewers. Such analysis can, of course, be most effective if all raw data are included as part of the submission.

The topic of institutional response and accountability was also covered by multiple speakers. For example, Raphaël Lévy presented his own horror story, conservatively titled “Inadequate Protection of Whistleblowers in France,” outlining the various retaliatory consequences he suffered for several years after exposing a set of fraudulent papers published by someone at his own institution.

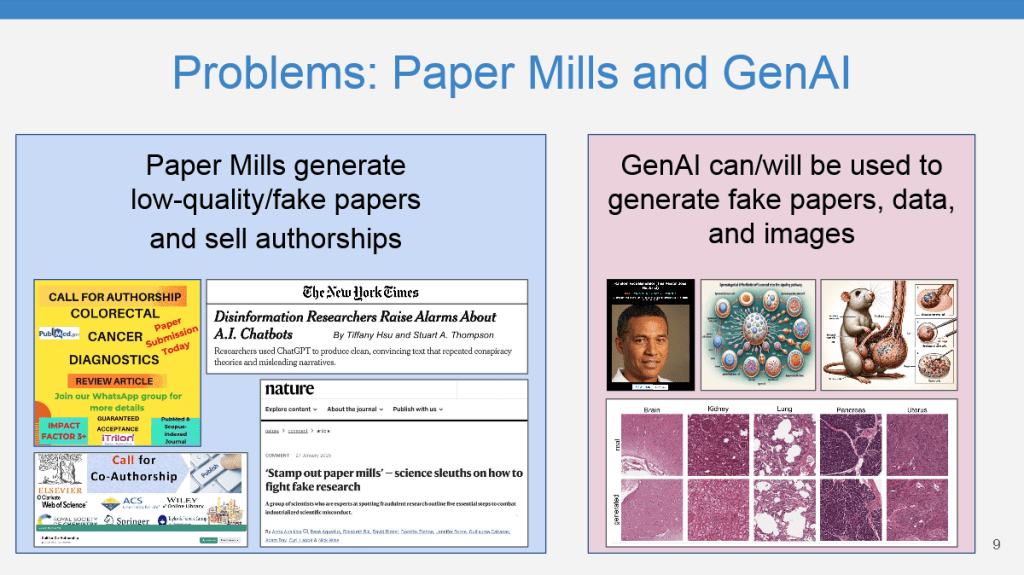

Several speakers, including Anna Abalkina and Guillaume Cabanac, discussed the rapidly growing problem of paper mills. Cabanac provided illuminating and humorous examples of the “tortured phrase” problem, which occurs when fraudsters try to bypass plagiarism detectors by mindlessly substituting synonyms.

My own take on paper mills and tortured phrases is that — while there is no question that every fake or plagiarized paper contaminates the literature — most scientists can immediately identify these paper-milled “products,” and many of them already know how to handle them (directly into the trash bin). While reading tortured phrases can also be entertaining, as soon as scientists encounter a phrase like “pinnacle flag to clamor proportion” and recognize it as a distorted version of “peak signal to noise ratio,” they — after they stop hysterically laughing — know exactly how to deal with that paper (once again, straight into the trash bin). So yes, let’s clean up the literature, but I think it is immensely more important to catch the “big fish,” i.e., high-stature investigators who serially publish problematic data. Such cases can mislead entire fields of research and lead to the waste of many millions in research funding, both in direct grant money spent on hopeless directions and in opportunity costs. I’m thinking here of fields like stem cells in myocardial infarction (Piero Anversa), beta-amyloid research in Alzheimer’s disease (Eliezer Masliah), and others. To me, this is where the real benefit lies — in preventing such “runaway trains” from leaving the station. Exposing these issues is much harder and far more challenging, both methodologically and, when the affected bigwig decides to sue the sleuth, legally as well.

UCL trachea transplants: Videregen sets lawyers on Liverpool academics Murray and Levy

Videregen, the Liverpool-based company which bought the trachea regeneration patent from UCL, deployed lawyers against the academics Patricia Murray and Raphael Levy, precisely via their employer University of Liverpool. Main issue is the parliamentary submission by Levy and Murray, subject to absolute privilege. Yet Videregen also cites from the confidential notice of suspected research misconduct…

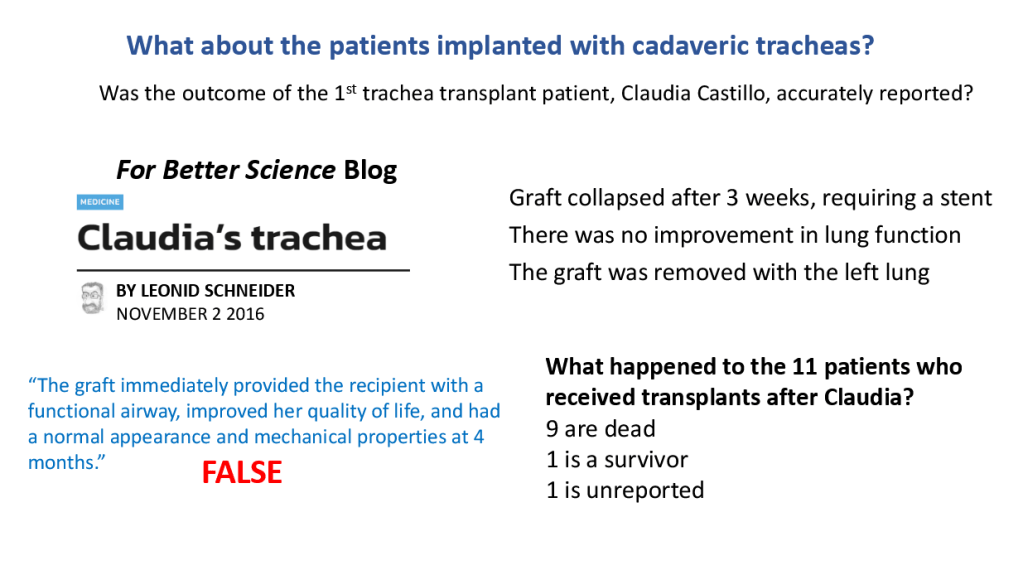

Clinical Research Misconduct

Obviously, when misconduct occurs in a clinical area, it can directly affect patient health and safety. Although the entire sad Paolo Macchiarini saga is well-known to all For Better Science readers, it was still a chilling experience to hear Patricia Murray discuss her personal involvement with the case. What I find worth stressing is that Macchiarini, of course, did not work in isolation, yet nearly all of the individuals in Sweden and the UK who played various roles in enabling, supporting, and/or protecting Macchiarini remain active and unpenalized.

In another talk, the legendary British cardiologist and whistleblower Peter Wilmshurst recounted 40 years of personal experiences investigating research misconduct, including high-profile cases involving medical fraud. Once again, his presentation highlighted the persistent lack of adequate institutional responses.

When Nancy Olivieri gave her presentation, the same themes of institutional self-protection, pharma company corruption, and retaliation against whistleblowers were re-emphasized.

Motherisk crook Gideon Koren now at Ariel University

The Israeli Ariel University recruited a doctor from hell to their newly established medical school: Gideon Koren, infamous for Motherisk and deferiprone scandals.

My immediate takeaway after the clinical session could be summarized by the following exasperated thought: “What are we all doing, getting hung up on flipped Western blots and duplicated histological images in obscure research papers, when some people are getting away with actual murder?!” (More on this later.)

Cultural, Social, and Geopolitical Dimensions

Several speakers discussed how cultural and geopolitical forces intersect with scientific integrity. Till Bruckner‘s talk on the “weaponization of integrity measures” illustrated how scientific integrity measures can be misused politically, economically, and culturally, raising the risk of collateral damage to innocent researchers. Along the same lines, Stephan Lewandowsky discussed the challenges posed by fraudulent research to the credibility of scientific literature, emphasizing the balance between rigorous accountability and overly aggressive policing. (My two cents: we are so far from overly aggressive policing that I really do not see this as a serious concern. I wish we were already at the point where we had to worry about this.)

Patricia Kingori analyzed the phenomenon of “shadow scholars,” primarily from Kenya, who are hired to produce fraudulent academic content, primarily for American and British college students. This talk made me wonder: if a significant proportion of college students become accustomed to cheating on their essays even before beginning, say, a PhD in a biomedical field, and if their experience teaches them that cheating is an effective way to get ahead without being caught—what does that teach them for the rest of their careers?

Li Tang presented an update on China’s massive investment in research and highlighted some of the country’s challenges regarding scientific integrity reform. It was clear from her talk that funding agencies are well aware of China’s severe scientific integrity problems and that systemic changes are necessary to curb research fraud. However, it was less clear to me what the necessary next steps should or will be. For what it’s worth, she insisted that the famous “cash rewards for publications” system no longer exists in China, and stressed that granting agencies now focus on the quality rather than the quantity of publications, which should have some mitigating effect on paper mill product “consumption.”

The full-service paper mill and its Chinese customers

An investigation by Elisabeth Bik, Smut Clyde, Morty and Tiger BB8 reveals the workings of a paper mill. Its customers are Chinese doctors desperate for promotion. Apparently even journal editors are part of the scam, publishing fraudulent made-up science.

The Official Consensus

As expected, there was extensive discussion around enhancing transparency, strengthening institutional accountability, protecting whistleblowers, reforming publication practices, adopting technological innovations, and recognizing the broader social and political contexts that shape scientific misconduct. However, in addressing these challenges, the conversation did not move beyond what I call the “standard solutions” in my book Unreliable — that is, ideas and initiatives which are palatable to official stakeholders but have neither worked nor will ever really work. Nevertheless, I list them below, using the solemn, official wording typically employed, which makes them appear more presentable but not one iota more implementable:

- Strengthening governance structures in academic and funding institutions.

- Developing advanced statistical and digital tools for detection and prevention.

- Advocating stronger protection mechanisms for whistleblowers.

- Promoting widespread adoption of open science practices.

- Reforming academic incentives and publishing standards to reduce misconduct opportunities.

Some Take-Aways

To be honest, I’m not sure what I expected from the meeting. I was hoping to get an update on the state of the “Research Integrity Field,” which I certainly did. I was also hoping to meet some of the main figures in the field, which I did as well—both those who are well-accepted by the establishment, like Dorothy Bishop, Ivan Oransky, and Elisabeth Bik, and many sleuths whose “official status” is less recognized. I also had the pleasure not only of meeting significant whistleblowers such as Patricia Murray, Peter Wilmshurst, and Nancy Olivieri, but even chairing their session. All of these individuals came across as serious, dedicated, and deeply concerned.

At the same time, it simply does not feel right that exposing bad science, forcing retractions, and triggering (rather sporadic and highly variable) consequences rest in the hands of private individuals — many of them working under pseudonyms and without any kind of legal protection. The mere fact that this is how the system currently operates is itself a problem. Moreover, I did not hear any plans or assurances from any stakeholder at the meeting indicating that this sorry state of affairs will change anytime soon. Academic institutions, publishers, and grant-awarding organizations remain largely uninterested in retrospectively cleaning up the literature, leaving this task to the sleuths — a real “David vs. Goliath” scenario (and, quite often, a Sholto David vs. Goliath scenario…).

Dana-Farberications at Harvard University

“Imagine what mistakes might be found in the raw data if anyone was allowed to look!” – Sholto David

At both the plenary sessions and small-group discussions, I kept asking attendees about their ideas for possible reforms and potential solutions. To my amazement, most were unprepared to discuss this matter. (It’s also possible that everyone at the meeting — except me — had long ago concluded that the system is FUBAR: there are no solutions, and they didn’t even understand why I was trying to raise the issue. But for a moment, let’s assume solutions might exist.) From the responses of those participants who did offer opinions, a few things became clear.

First, the clinical and preclinical sides of the problem should be separated. On the clinical side, there are already plenty of rules, regulations, IRBs, disciplinary boards, and legal frameworks; thus, the solutions must largely focus on better enforcement of existing processes. On the preclinical side, however, it appears that even the legal and regulatory framework is murky, down to fundamental questions like, “Is the production of fake data an illegal activity?” or “Is the attempt to publish false data a criminal offense?” or “What would happen if someone walked into a police station and reported a scientific misconduct-related matter?” Many attendees supported the idea of setting up a separate regulatory body or even a specialized police enforcement unit (by analogy with existing units for art or financial fraud). And (almost) everyone agreed that serial or severe misconduct should, at the very least, result in revocation of the individual’s academic credentials — similar to how, after repeated violations, people can lose their driver’s license.

Second, there seems to be significant disagreement among various stakeholders about the focus of reforms. “Establishment” players (representatives of funding agencies and academic integrity offices) prefer to emphasize prevention: better training, improved data collection, and better archiving practices. In contrast, the sleuth and whistleblower communities clearly advocate stronger penalties and even the introduction of new (legal) categories to clamp down on severe and repetitive scientific misconduct — even if it “only” involves preclinical/basic research.

As expected, I remained unimpressed by most members of the publishing industry I met at the meeting. Representatives of major publishing houses tried to assure me that they’re doing everything possible to improve research integrity and reject substandard or fraudulent papers. They claimed to be “totally open and eager to introduce new integrity measures,”…. provided these measures don’t affect their profit margins. I spoke with many academic journal editors who seem to have good intentions, yet many of the journals they manage still do not employ full-time statisticians, do not require the submission of raw data, and openly acknowledge that even if they catch a problematic or fraudulent paper, it will eventually end up published somewhere else.

But the group that frustrated me the most were the representatives of the “establishment.” Prior to attending this meeting, while writing the final chapter of Unreliable, I spent considerable time thinking about the various stakeholders and their roles. I concluded that, inevitably, some percentage of individual investigators will cut corners or engage in questionable research practices (or worse), given that the pressure is immense, the incentives substantial, the chance of getting caught low, and the penalties minimal even if caught. I also concluded that academic institutions have numerous conflicting interests, such as securing grants and protecting their reputations and these interest will severely limit their interest in true integrity reforms. (Indeed, many universities seem to place useful idiots into their research integrity offices.) Moreover, it is plain to see that the publishing industry, being profit-driven, remains more interested in profits than fundamental reforms. Thus, by elimination, I concluded that if reform is ever to occur, it must be driven from the funding side — imposed on the entire “system” by grant-awarding organizations and their governments.

Andrew George and the Virtues of Research Integrity

“One of the UK research system’s strengths is having established processes that allow for this review so that we maintain an accurate and robust research record. Promoting and improving this system, and encouraging more openness and transparency, is why I became involved in the UK Committee on Research Integrity.” – Andrew J T George

After the three days of the FAIRS meeting, however, I am less hopeful. Representatives from the official side offered weak guidelines, non-binding “concordats,” and — in some cases — blatant cop-outs. More “coordination is necessary”, more “meetings are necessary”, “we must act gradually”, “we are doing all we can”, “you can already see our progress on our website”, etc. One representative of a British funding agency, during a small-group discussion, engaged in striking “whataboutism,” stating, “Look around, there are all sorts of problems, cheating, and misconduct in all walks of life; for example, look what’s happening in the Catholic Church.” I never thought I’d see the day when priests’ kiddie-fiddling would be cited as an official justification for a lack of comprehensive scientific reforms. In sum, I went into the meeting believing that grant-awarding agencies might be part of the solution; after all, if anyone, they should care where their money goes. Now, I fear that instead of them being part of the solution, they might instead be part of the problem, just like the other “stakeholders”. But, to be fair, there were relatively few official representatives present at the meeting — an issue also pointed out by Ivan Oransky, who advocates incremental rather than radical approaches but still feels that government and funding agency representatives must be convinced to initiate some reform.

Little Rays of Hope

There were a few bright spots presented here and there. Nick Brown described various methods (e.g., GRIM) to detect numerically impossible research findings, and he hinted at the existence of many other such techniques. Similarly, John Carlisle explained several rigorous statistical methods for detecting fraud in clinical trial datasets. If such methods were broadly implemented by journals at the screening stage (at least by those journals that actually care about what gets published), some progress could be made; many problematic papers could be spotted and eliminated right at the outset of the refereeing process.

Lex Bouter, King of Research Integrity

My uninvited contribution to WCRI 2022

But — as mentioned earlier — if one journal rejects a problematic paper, another one, typically a lower-tier journal but quite possibly still an indexed one, could (and probably will) publish it instead. One journal editor explained to me that the publishing industry had begun creating a networked (black)list of problematic papers and bad actors, along with a warning system through which all journals could be alerted when a fraudulent submission appears. However, it seems a class-action lawsuit halted this initiative. One can only hope that this legal matter will soon be resolved, as a journal-wide warning system could significantly reduce the tsunami of bad scientific papers that we should brace ourselves for as the AI revolution advances.

Uri Simonsohn (aka one-third of “Data Colada”) explored statistical methods to detect fraudulent results and introduced a practical system (“AsCollected”) aimed at preventing misconduct by ensuring data integrity and (hopefully) reproducibility via data tracking and preregistration. He did not have enough time to explain the entire system in detail but mentioned it will be piloted by a social science journal, with the current setup mostly tailored to social science-type studies. While I can see how the system might work with formalized protocols such as clinical trials or social-science studies, I suspect it would require significant tweaking to make it similarly useful for fast-moving, rapidly changing preclinical research, where experimental designs frequently evolve based on week-by-week data collection.

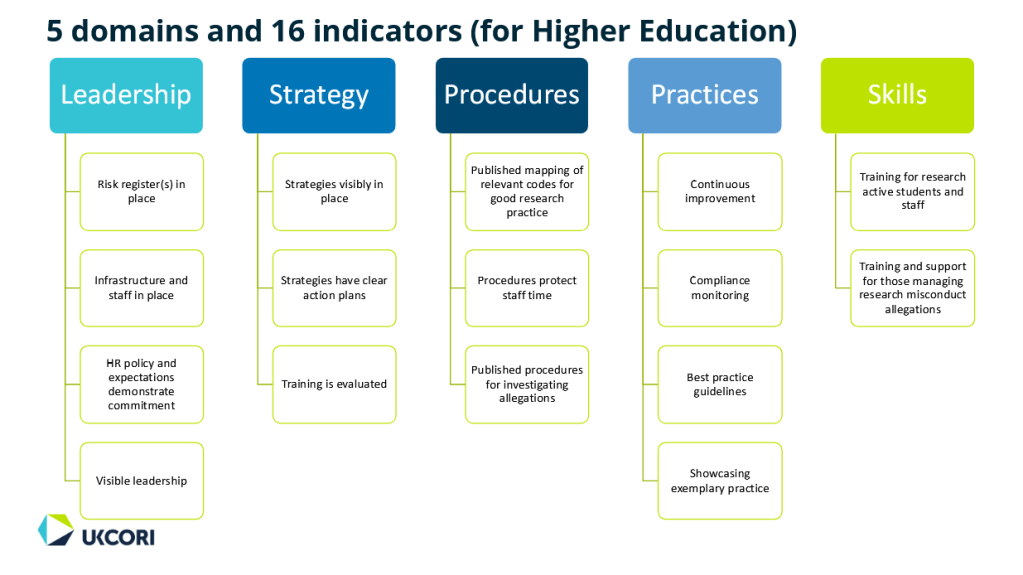

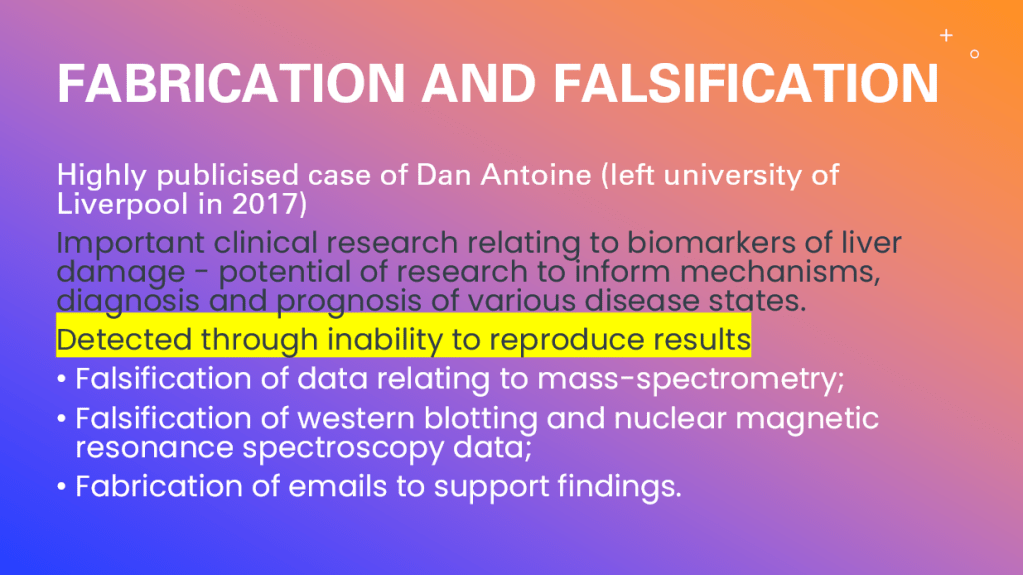

Finally, Liz Perkins (who holds the strange title of “Named Person for Research Integrity” at the University of Liverpool) presented her university’s efforts to combat research misconduct. Her talk went well beyond platitudes like better governance, accountability, and education and described concrete processes that are already in place, as her university is taking the matter extremely seriously. (Admittedly, the system in Liverpool was established in response to their infamous Dan Antoine/HMGB-1 diagnostic assay fiasco — but better late than never, I suppose.) I particularly liked their routine use of “random spot checks” of laboratory data and research practices — as opposed (or in addition) to the usual reactive processes triggered by whistleblower reports or PubPeer comments.

There was one additional bright idea mentioned during a discussion, made by Nick Brown. He suggested that funding agencies should establish and operate their own journals, mandating that their grantees publish there. Such a system, of course, would not charge APC fees, could be connected to open databases and even to pre-registration of the studies and could perhaps eliminate some of the temptation and hubris associated with publishing in “luxury journals.”

In Conclusion…

So, after spending three days at the FAIRS meeting, what have I learned? First of all, if each time somebody mentioned the “tip of an iceberg”, I would have collected 5 quid, I would have left Oxford with a wad of cash. Instead, I left Oxford with the realization that scientific integrity control feels like a never-ending game of whack-a-mole — except the moles are actually ‘crafty’ scientists, criminal publishing gangs, massive institutional blind spots and a publishing system powered by profit margins and wishful thinking. Sure, we have heroic whistleblowers and brilliant sleuths working in their free time, but real institutional accountability remains depressingly absent. I heard about some neat tools like statistical fraud detection and a few useful ideas like data audits of randomly selected research groups, but let’s face it: these are band-aids on bullet wounds while the big fish continue swimming untroubled through the system. Unless governments and funding agencies stop hiding behind toothless guidelines, non-binding concordats seeking to “support” research integrity (support? how about establish and then enforce!), and spectacularly creative excuses (“Hey, at least we’re not as bad as the Catholic Church!”), meaningful reform seems about as likely as publishers volunteering to cut their profits. Until then, the integrity crisis continues, with whistleblowers getting sued and fired and fraudsters getting promoted. The rest of us are left to laugh bitterly at tortured phrases and ridiculous excuses, while we are bracing ourselves for the upcoming tsunami of AI-generated scientific garbage.

Editors and other real papermill heroes

“Long story short, we investigated our published papers and then retracted those with data integrity issues. That is it.” – Dr Heather Smith, Editor-in-Chief

In the meantime, the “science integrity meetings” will continue. For me, this was the first one I ever attended, and I found it extremely useful: it brought together representatives from multiple sides of the issue, and the discussions were honest and stimulating. I was quite surprised to discover that there has been an entire ongoing series of meetings nominally dedicated to scientific integrity since 2007—apparently without much effect. There will also be two more “integrity” meetings this year alone, one in Croatia and another in Australia, and the “official” series will continue next year at yet another fancy location, this time in Vancouver, Canada.

I only wish future meetings would place more emphasis on policy changes and action plans rather than becoming mired in definitions, guidelines, and endless committee deliberations. I also believe the presence of more governmental representatives would be an important addition to future conferences, so they can see first-hand the state we’re in, understand what’s coming, and realize how quickly the situation could deteriorate from bad to disastrous if significant reforms are not implemented. Perhaps this would serve as a wake-up call, finally steering them in the right direction.

Coda by Leonid Schneider

Since this is my own website, I can shoehorn here my own opinions without anyone putting their foot down and showing me out.

Now, I do agree with Csaba about the pointlessness of these stakeholder discussions on research integrity. Except that their pointlessness is the actual point, similar to industry’s greenwashing of their climate and environment damaging products: everyone can continue with wasteful and destructive activities while having a good conscience.

I do disagree that the way to go is to convince scholarly publishers and academic stakeholders about the need to crack down on science fraud. They are grown-up and financially very successful people, so it is very unlikely they waited for you to educate them with your PowerPoint presentation about the right way of thinking.

Publishing executives only care about revenues and profits, and those are tied to reputation, and this is exactly where publishers can be hit and made to cooperate. In fact, they only became United2Act on Asian papermills because of the reputational damage from the scandals exposed by my sleuthing colleagues. And even there, publishers try to titrate the right amount of retractions vs inaction, because of course their industry would immediately collapse without the papermills.

Academic stakeholders, i.e. executives of universities, research institutions and funding agencies, also know which side their bread is buttered. Even if they are not research fraudsters themselves – they arrived into their top jobs only because of professional networks. Which quite often include science cheaters, academic bullies and harassers, and their abettors. Let me remind you of just two members of the Senate of the German Research Council, DFG:

Fulda & Debatin: Reproducibility of Results in Medical and Biomedical Research

“Basic and advanced training for researchers should focus much more on self-reflection, openness and a culture of error acceptance.”

If you wants something to be done against smoking, you don’t preach to Philip Morris, no matter how clever and science-proof your arguments are. You will only succeed by appealing to the public and its elected representatives, directly and via the mass media. It is the same for science fraud.

Sleuths I work with do the most important task: they find fraud, and record it on that immensely revolutionary website, PubPeer. You can help make their findings reach the public and politics. If you are a university professor, your status elevates you and your opinion will be heard, all you have to do is to try contacting the media or elected MPs, and to alert them to the true state of science in your home country.

Most (if not all) high profile research fraud scandals only exploded with the consequences to perpetrators because of the coverage in mass media. Once it’s in the news, universities and journals have no other choice but to act on fraud. If as a journalist you want to wait out for academic “due process” to run its course (to the predictable whitewash), there will be very little or more likely nothing at all for you to write about.

Even though my website reaches all the right people, it alone cannot generate the required impact from the society and politics, for that the PubPeer evidence needs to be picked up by mass media. And the journalists will only report about science issues when professors advise them. Again, ask Simone Fulda.

Too often instead, journalists, especially science journalists, see themselves as cheerleaders for science and will never write a bad word about a scientist, certainly not about an elite scientist, because this is what the antivaxxers and fascists do, right? Actually, even antivaxxers and fascists listen to scientists, it’s just that they have their own “scientists” to follow.

The Dead Geier Sketch, RFK Jr version

“David Geier is the ideal fit to the purposes of RFK Jr. For the only reliably loyal underlings are incompetent ones who know they have no future anywhere else. ” – Smut Clyde

Others report about retractions, For Better Science causes them. By the way, why don’t we have an automatic retraction database still? The Retraction Watch Database is still compiled entirely manually, despite having been sold to Crossref. Maybe YOU, dear reader, can code something?

Every one of you has much more talent, power and influence than you think you have. If you need a role model, look up to Patricia Murray or Elisabeth Bik.

Research integrity is a grass-root effort, a bottom-up approach where all of us can contribute, one way or another. No change, however incremental, will happen because some senior exec saw the light after attending a research integrity lecture.

It’s up to YOU, do something.

Donate!

If you are interested to support my work, you can leave here a small tip of $5. Or several of small tips, just increase the amount as you like (2x=€10; 5x=€25). Your generous patronage of my journalism will be most appreciated!

€5.00

Thanks for the write-up.

I’d like to see more research about how and why academic fraud typically occurs. From what I can tell in my field, a common scenario is a researcher jumping to conclusions and building a ‘story’ based on questionable foundations, then later performing poor-quality experiments, or outright fabricating data, to justify their earlier assumptions. The steps needed to identify and stop this behaviour are distinct to the steps needed to prevent different types of misconduct.

Complicating things further, the norms and practices seem to vary widely between sub-fields, even closely related ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wrote a whole book about that; the first 70-80 pages are pretty much about what you are asking: inappropriate academic pressures, motivations, perverse incentives, unhealthy competition, etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What I really would like to know is was it ALWAYS this bad? In other words, was it true than in 1970 that 50% of the data was irreproducible by other labs? In 1940?

Maybe so, but less due to fraud?

Great book, by the way. Really enjoyed it. Interesting to read that between lab variability may due to stuff like lipopolysaccharide and estrogens. yikes!

LikeLike

Nice read.

My two cents of what should be done right away:

LikeLike

My old blog post on this topic:

LikeLike

Seems like the Electrochemical Society already tried something like that, almost 10 years ago. See here:

https://www.electrochem.org/for-science-or-for-profit

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1149/2.011164if

If it would have been wildly successful, we probably have heard about it by now. Nevertheless, I think it would be worth trying something similar in biomedical sciences. Elsevier, Springer etc have had plenty of time to use some of their profits to improve their ways, if they wanted to. Cleary they do not want to. So they should be replaced. I will write a ‘manifesto’ and try to get some big name signatories.

LikeLike

The problem is metrics. Scientists and admin need measuring tools to assess scientific performance. Which is the number of papers and impact factor.

Worked great for generations. Never change the running system.

Look at those research integrity losers how little they published, no wonder they grind axes.

LikeLike

Scientists and admin need measuring tools to assess scientific performance, just like Pharma needs measuring tools to assess scientific performance. But somehow pharma manages to do this assessment quite effectively (at least better than academia where people climb the ladders with guest authorships) without authorships/counting number of papers published. There are several ways to assess productivity.

1- Authorships needs to be removed from academic publishing all together. Many fields share knowledge under an institution/company name without naming contributors. Employees gain credit by getting a salary to live a decent life. Many write eg. due diligence reports in a firm and submit it with the firm’s name or partners’ name on it only. When they apply to their next job, they are not asked to count and list how many reports they wrote/have contributed to. Nor a physician is asked to write down how many patients s/he treated in her/his job application. Removal of authorship will solve authorship disputes, create collaboration over competition (also competition over who is better at getting his/her name included in papers as guest author, something that got out of control), eliminate paper mills, prevent researchers accepting to do unpaid work just to have their name on a paper and institutions benefiting from human capital withouting spending a cent, by substituting financial compensation with authorship compensation.

2- Many in research focus solely on publishing the next paper and they forget why they do what they do. It’s human nature so it happens. Pharma companies invite patients to tell their stories, remind their scientists the meaning of their work, its end point. When one is reminded that the photoshopped blots are affecting an individual’s life, they may think twice and also feel more motivated to do real science when their focus shifts from paper to patient. Even in university hospitals, it’s very unusual for a research lab to invite a patient from next door (clinic) and remind its team why their work matters.

3- In no tech/pharma that I’m aware of, one can be the CEO or manager, and consult to 5 other companies or be in their advisory boards, and have her/his own two start-ups running on the side, where he is an acting Chief Technology Officer or Chief Medical Officer. However in academia, many physician/scientist faculties teach clinical trainees, treat patients, do research, train/supervise their research trainees, write grants, write grant progress reports, serve as Editor in Chiefs, take leadership roles in medical associations, presumably ‘substantially’ contribute to countless papers a year that all meet authorship criteria, and one day is only 24 hours (including bed time) ! There should be regulations that set realistic expectations and limit outside work. Nobody is superwoman or superman and adults should be able to grasp that. In addition, if a PI is allowed to consult only a few companies, younger experienced scientists/junior faculty can also be given a chance to consult the remaining ones – their input can also valuable.

Sorry this was too long, but sometimes there are very easy solutions to complex problems that were not supposed to exist in the first place. If we can at least start with those, that’s already a step forward. Somehow I don’t see enough people in academia discussing these topics even among each other, it seems that many accepted it as is. And I’m not sure if these obvious ones even need big conferences and hours of panel discussions. If senior faculties cannot (do not want to) understand it, I’m sure public who puts so much trust on the scientists and who pay their reagents and salaries, can.

LikeLike

I think research integrity was always the exception, and not the rule, at least in my experience of academic research across 6 labs in various biomedical fields (in the past 20 – 25 years). The system is based on trust, not transparency, and the ends are furtherance of funding, not truth. It’s a hydra–there are no “big players” and misconduct happens from bottom to top. I see high-profile (and low) publications in my field(s) and think “that’s fake, that’s fake, there’s another one.” It’s not an exception–it’s endemic.

LikeLike

Thanks Csaba this was an enjoyable read. I don’t really have in my mind anything that would remedy the situation beyond the platitudes usually trotted out that you noted. I do feel strongly that punishing people who commit research fraud would be cheerful to watch, but a lot of people find that distasteful… Surely we punish the whistleblowers enough already, so wouldn’t it only be fair?

Other than that, I would just suggest spending the money earmarked for research on more useful things where it won’t be wasted. I’d happily divert half of cancer research funding into gorilla preservation instead 😂 Although I suppose most people actually want to do the same amount of science, just without the fraud. Surely it’s time to ask how many PhDs are too many though?

Finally, a note on preclinical research… Many Phase I clinical trials are initiated on the back of hype papers with flipped western blots and duplicate histology. Such trials are often missing control groups too. Off the top of my head I think it’s the case that most cancer drugs approved through the FDA’s fast lanes don’t work. So I think attacking the flowing torrent of “promising molecules” and “targeted therapies” really does help patients who otherwise might be exposed to potential side effects in these trials, and continued harm when the ideas are waved through on promising mechanisms and cherry picked endpoints.

Thanks for the write up and coffee ☕

LikeLiked by 1 person

I 100% agree with all of this. And please don’t think that many of us working in biomedical research don’t appreciate what you sleuths are doing. Privately, almost all people love it. Publicly, to speak about it, let alone stand by the sleuths or try to secure some legal status or protection or recognition for you… that is another matter, unfortunately.

And yes cancer research and the approval path (on biomarkers or on non-significant ‘life extensions’ – coupled with immorally high drug prices – is highly problematic (one of many topics I have put already aside for my next book…)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, the field of “life extension” is particularly rife with horeshit. I’ve had a front-row seat at it for years.

LikeLike

Thank you for this great read Csaba.

Regarding the rejection of a problematic paper by one journal and its subsequent publication by a lower-tier but still indexed journal – I believe it is unfortunate that when ‘some’ reviewers invest significant time carefully reviewing a paper and writing detailed concerns, all the time and expertise of reviewers is often thrown away when the paper is rejected – because the same paper generally bounces from one journal to another until it finds crack in the review process and gets accepted. This is not only a questionable form of gate keeping but also not an efficient use of human capital, thus scholarly resources. The very same publishing industry, which is building a networked blacklist of problematic papers and back actors, could easily build a centralized system where all previous and current reviewer comments of a manuscript are posted anonymously with each submission/re-submission, thus the next reviewers could be made aware of the previous comments/potential errors detected, instead of wasting time to re-detect the same errors (if they were to detect them at all) and doing redundant work. When all these review comments are publicly accessible/transparent and possibly linked to the published article, also after publication, the subsequent reviewers may be more alert during their review process and editors may also think twice before accepting a paper. Some publishers already started doing some of it and now it just needs to be centralized for all. Of course, some authors may change eg. the title to show it as first submissions but one can come up with solutions to track perviously submitted articles.

Leonid, what a piece of art ! One of the best that you have ever written. Every researcher should print it out, highlight the last two words in yellow (do something) and hang it on their walls.

In this context, I can’t help mentioning these new Science Guardians, also established in November 2024:

https://toarumajutsunoindex.fandom.com/wiki/Science_Guardian

https://x.com/yenpress/status/1905698474789630460

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words!

But once again: the publishers, both commercial as well as “non-profit” are not interested in preventing bad papers from publication and thus losing revenue.

That’s why all big publishers have a system of downhill submission, where a rejected paper and its peer review are forwarded house-internally down the impact factor chain until one downstream journal accepts it.

Authors eagerly participate, since it saves them time and effort.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks alot for your report. Any idea if the participants have discussed the current policy of LOWI and of all at LOWI https://lowi.nl/over-lowi/#samenstelling-LOWI to advice Dutch universities to throw away research integrity complaints when the complainer has published his complaint on a public part of the internet?

LikeLike

There was one person from the Netherlands who seemed to have some connection to their research integrity system or offices. He did not say much during the plenaries or the breakout sessions. As far as I know the acronym LOWI was never mentioned nor were any specifics of how the Dutch handle complaints were discussed.

LikeLike

Thanks for the response. I hope someone is able to remember the name of this person from The Netherlands.

A recent advice by LOWI also reveals that it is no problem for LOWI and for all at LOWI that Dutch researchers publish their findings in the IJVTPR https://ijvtpr.com/index.php/IJVTPR/about/editorialTeam and that Erasmus MC is listed as (single) affiliation of the author in question.

The case in question refers to a paper by a.o. Rogier Louwen, an antivaxxer who was sacked by Erasmus MC for already quite a while when this paper was submitted to the IJVTPR. Apparently, LOWI and all at LOWI were not aware of the backgrounds of people like for example Brian Hooker and Richard Fleming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just to get it exactly right, can we say that if the frauds in a study are shown on Pubpeer, it ceases to be evidence for the Dutch authorities and they don’t care? I hope I misunderstood. If this is really the case, I can understand why so many Iranian papermillers and citation gang members prefer to cluster in Dutch universities. Too bad. Too sad.

LikeLike

Very high quality report and comments. Keep fighting the good fight. One suggestion I would add is that Publons credits should be conditional on the editor’s approval. I am sick of other reviewers – these days often only one – submitting a matador’s wave paragraph that could be used for almost any paper. You know they are accepting everything that comes their way just for the credits.

LikeLike

Wrong, wrong, wrong.

Since even I started to receive business offers to get client papers published in special issues in return for $500-100 per paper, rest assured those reviewers don’t do it for credits but for money.

LikeLike

I was talking more about established journals, where editors presumably still have some sense of responsibility. Not that I have anything against outright vanity publishing.

LikeLike

Just for context. Many people have no idea what an extraordinary business ‘scientific publushing’ is.

The global scientific publishing market is substantial and continues to grow, though it’s dominated by a few major players. As of recent estimates:

LikeLike

All good, but how do all these fraudulent papers pass through peer review? Who wrote these reviews and what is written in them?

I am not naive to expect that a reviewer (or even 2-3 of them) can detect fraud during peer review every time but still some of the described here misdeeds are quite obvious. We desperately need full transparency in peer review for all and especially for the retracted papers, and of course including reviewers identities. Editors communication should be unveiled in the same way, too.

This of course will not solve the problem but at least will reveal the mean practices of publishers, editors and reviewers. After that my imagination is poor to envision how to proceed next.

LikeLike

There are several levels to this. As Leonid writes, sometimes, there is no peer review or the review is fake. I have not experienced this however.

What I mostly see is that the reviews are worthless, in both directions. Several of my friends have gotten “this is no contribution to science” on obviously OK manuscripts. We got “the applicant has no expertise in the field” on a grant application, after having tens of good papers in the field. And the opposite, I write a very careful 2-3 page review, with justified “reject” while the other reviewer(s) offer “the manuscript is generally well-written and can be accepted, fix a typo on p.3, l. 25”. One time I got a very poor manuscript to review and wrote a lengthy text on how to improve it (it was a strong reject, no intro, no discussion, poor data presentation). The journal published the text without any changes from the original submission. I certainly wouldn’t want to be listed as a reviewer on that one.

I did not get any fake stuff for review (yet) but one time I noticed the paper was a copy of previous work – intro was verbatim copy, work was done but with less quality. It was a reject because of text plagiarism. But most of the stuff I see for review are apparently honest works of (very) low quality. Needless to say, it is much easier to review a good manuscript than to provide justification on why you suggest a reject.

Our own reviews are hit or miss, a good review is rare, you hope for the lazy reviewer and fear the vitriolic one, who will spend pages on minor detail of your work, sometimes even clearly misunderstood, perhaps for lack of experience (i.e. not qualified for review, not a peer).

I think that publishing the reviews, with names, alongside the text is an interesting idea, as is an option to express concern that the reviewer is not a peer or did a very poor job. But there is a serious lack of good reviewers nowadays. Certainly one of the problems in the industry. And we all want+need to publish.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. What do we have now: mostly worthless reviews with fraudulent papers.

From a personal experience, I have already been accused of autoplagiarism twice in order a manuscript to be rejected after lengthy reviewer process. The first time it was by an editor from the arXiv version of the same manuscript, the second time very recently by a reviewer comparing a previous published study whose review lead to a reject. Both came from Elsevier journals and even the lead editor of the second journal has taken part in revealing fraud and commented here.

Nothing personal, just business.

LikeLike

A lot of the (paper mill) fraudulent papers is not just about ‘fake’ papers, it is also corrupt editors and corrupt reviewers. They are all in on it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a great write-up. I love the reused histogram.

As for the solution, it’d clearly need to be multi-level. One thing I do not see much is pressure from funding agencies. I have seen frauds getting great funding (ERC, look in the mirror!), sometimes even repeatedly. Even when exposed, there are no repercussions for the fake scientist or the institution itself. Besides, with their inflated h-indices, do they review grant proposals? Do they review manuscripts? Do they serve on scientific boards? Of course, the best cheaters are often likeable, excellent self-promoters, great bullsh*tters loved by the media and PR depts. of research institutions (“highly-cited researcher”). If you’re not excellent in the field, you’ll never figure out that anything is wrong. Even if you are and do, there’s often no clear proof and there’s nothing you can do about it, just perhaps tell friends at the coffee break. The best cheaters will not be caught copy-pasting blot spots or hand-drawing spectra (some will though, can we get rid at least of those?).

What I’ve met with is an attitude that “he’s made some mistakes in the past, we think he’s clean now” and “most of his work is clean”. Which translates as “he gets us lots of money and prestige”. Personally, I do not know where the boundary is, but science is based on trust. Once you lose trust in someone’s results, is that reversible?

LikeLike

This is one of the most enlightening articles I have read recently, thank you. It’s a bit sad that despite so many valuable actions, there is still no idea of taking organized action against scammers. You mentioned it too. I guess a deus ex machina is expected. He will come and clean everything. That’s a bit disappointing…

I agree with Dr. Schneider on two points. First, there has never been overly aggressive policing. Positions in universities, administrators, decision makers, ethics committee members, publishers and many others would not be so comfortable. In addition, I think the most useful thing at this stage would be a firm and swift overly aggressive policing. The tens of thousands of problematic researchers whose fraud has already been exposed and proven, but who continue to exploit legal loopholes and carry on as if nothing has happened, should be fired if necessary, prosecuted for misuse of public funds, and deported if necessary. This is how we can most clearly protect the future of academia and the labor and virtue of the many new PhD students entering academia.

Secondly, I fully agree with this approach “It’s up to YOU, do something.” On some of the works shown on Pubpeer, the authors of those works write mocking comments under the name of an anonymous user, saying that nothing will happen and nobody cares about them except only you. But I think the opposite, that it will definitely grow and grow, first individually and then collectively, and eventually purge the academy of the narcissists who are not only scammers but also mock those who expose them. Maybe not today, but definitely one day.

Publishers, university administrators who benefit from these scams and many more… The people we report to are thinking about how to professionally siphon off the evidence put in front of them instead of evaluating it. In the current situation, it would be unrealistic to expect a solution from these profiles. We truly do need to move from the bottom up.

LikeLike

Folks, there ALWAYS was aggressive policing in universities!

Against whistleblowers, those who refuse faking data or having sex with the boss, and other troublemakers.

Universities have no qualms about sacking people and making sure they never get a job again.

It’s just their priorities are money and loyalty.

LikeLike

It’s impressive how the FAIRS meeting brought together so many leading voices in research integrity.

LikeLike