Olivier Voinnet, the disgraced former star plant scientist and professor at ETH Zürich, is apparently on extended sick leave, his lab members have been redistributed to other research groups inside the faculty. This I learned from several independent sources, which made the information sufficiently reliable to share here. Previously, Voinnet was investigated by two expert commissions, one very secret by CNRS at his former Institut de Biologie Moleculaire des Plantes (IBMP), and another, more transparent one, at ETH (report here, my overview of the Voinnet scandal here). There, the investigative team comprised of four peers, two of whom were Voinnet’s faculty colleagues, and one was Witold Filipowicz, professor at Friedrich Miescher Institute in Basel. Filipowicz had been evaluating Voinnet’s research as IBMP review board member in 2008, before he nominated him for the 2009 EMBO Gold Medal:

“Olivier Voinnet’s discoveries represent true breakthroughs in his field. He has written several illuminating reviews recently, and participated as a speaker in many prestigious meetings. I consider him to be one of the most talented, original and effective young scientists”.

Update 8.04.2016: The supposedly impartial Voinnet investigator Filipowicz was also a recipient of the 2014 Chaire Gutenberg at Voinnet’s own IBMP as well as neighbouring IBMC in Strassbourg. The Gutenberg Chair is financed by the Alsace Region and the Urban Community of Strasbourg with € 60,000 of which € 10,000 went to Filipowicz personally as ‘Gutenberg Prize’ and € 50,000 were awarded to his host, the teams of LabEx NetRNA of IBMP and IBMC. Coincidently, one of LabEx NetRNA teams is still headed by Voinnet’s IBMP lab keeper and key partner in data manipulation, Patrice Dunoyer.

Under such conditions, it is hardly surprising that the ETH investigative commission concluded that Voinnet’s research was still largely reliable, despite his inexplicably compulsive urge to manipulate his perfectly good experimental data. As ETH press release then announced, Voinnet research was “Conducted properly – published incorrectly”. Well, this depends what ETH leadership understands under proper research.

Below I will show evidence from Voinnet’s peers that the published experimental evidence for his bold discoveries was shaky even before the data manipulations were discovered. Finally, I could not find a single lab which could confirm to me that they reproduced his results.

Instead I found those, who were able to disprove them. What is left of the whole affair, are seven retractions and a large body of corrected, but very questionable literature. These zombie papers continue to pollute the research field of RNA interference (RNAi) and of the wider life sciences. The most notorious paper in this regard is Deleris et al Science, 2006, which even the ETH commission wanted to see retracted, but which the journal chose to correct instead.

An interested reader of my blog, who is also an active scientist, chose to scrutinize this paper and its correction.

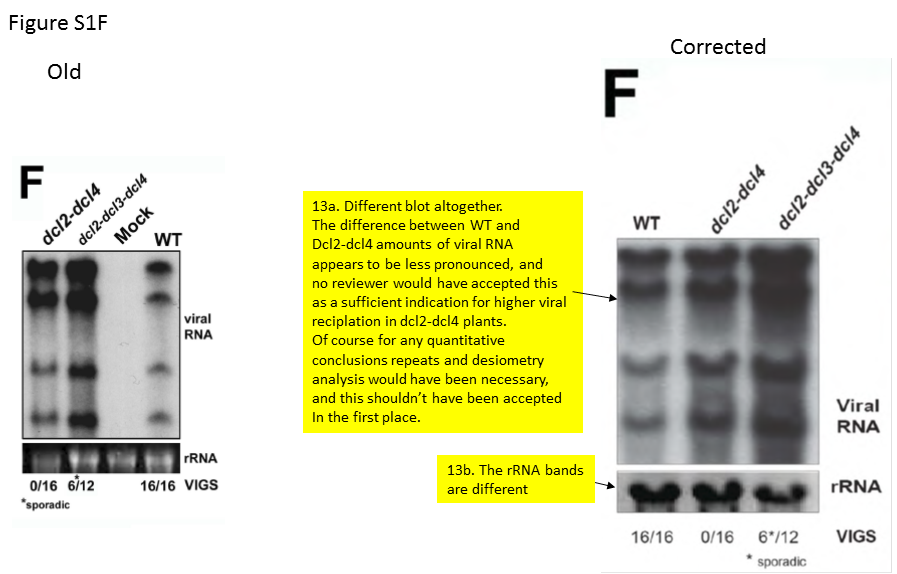

The scientist (whose image analysis and summary report are available for download), judges:

“It is a quantitative study (“hierarchical action”) in which the observed ratios of siRNAs within samples and the ratios of the amounts of viral RNA between samples were essential for making the conclusions. Regardless of the picture manipulations, it is already absurd that the experiments for the six figures were seemingly only done once, because this type of quantitative analysis requires repeats and statistical evaluation. The exchange of the correct pictures for the erroneous/manipulated ones led to differences in perceived ratios of amounts of RNA, making the figures agree better with the explanatory models postulated by the authors. At least in several cases this appears to have been done intentionally.

A recurrent reason for picture manipulations seems to have been that the authors did not include internal controls in their gel experiments, despite that such is a prerequisite for allowing quantitative comparisons. Several of the manipulations concern the inclusion of fake controls”.

James Carrington, head of Danforth Plant Science Center in USA and Voinnet’s collaborator on the Deleris et al paper, previously claimed no knowledge of the upcoming correction. He did not reply to my request to comment on the above analysis.

Update 17.04.2016. After I forwarded this article to Science senior editors and AAAS leadership, the journal’s Editor-in-Chief Marcia McNutt has commented over Twitter:

What about Voinnet’s other papers, especially those not even corrected so far?

Prior to the scandal, Voinnet used to be one of the leading scientists in the research field of plant pathogen defense and RNA interference. Voinnet’s PhD advisor, David Baulcombe, was one of the original discoverers of the RNAi mechanisms of plant defence against viruses. The Nobelist Tim Hunt expressed in a Science article his surprise that Baulcombe’s then-PhD student Voinnet did not receive the 2006 Nobel Prize for his role in the discovery of RNAi.

The science behind the discovery is such: the viral mRNA is met inside plant cells by their matching anti-sense RNA, which then together form double-stranded RNA. These RNA molecules are then degraded by DICER proteins into the short interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes. When loaded into the appropriate RISC protein complex, siRNAs help recognize and destroy the corresponding viral mRNA in a sequence-specific manner. There are different DICER-like (DCL) proteins, and different RISC complexes, which adds a wide range of diversification to the RNAi machinery. In the standard plant model organism Arabidopsis DCL3 generates siRNA fragments which are 24 nucleotides long, these are loaded into a RISC complex containing the AGO4 protein (of the Argonaute family). The 21-nt long siRNA is formed by DCL4 and is loaded onto AGO1-containing RISC complex. All these details become very important when discussing the true impact of Voinnet’s RNAi research.

Voinnet continued working on RNAi in plants. His biggest discovery as young research director at the in Strasbourg IBMP was the nature of the mobile silencing signal in plants. The phenotype, observed by plant scientists from grafting experiments (where a root from the plant of one genotype was grafted to a shoot of a different genotype), was striking: plants were able to initiate gene silencing throughout long distances, across the graft (Palauqui et al, EMBO J, 1997). When a transgene in one part of the plant becomes silenced by RNAi mechanism, this silencing can spread throughout the organism. First the signal spreads locally, from plant cell to plant cell through the plasmodesmata. Eventually, it reaches the phloem and then spreads systemically to the cells at the opposing end of the plant. There is obviously a mysterious mobile signal that spreads the silencing form one end of the plant to another. But what is it?

Until Voinnet postulated his evidence; the issue was an academic debate with many competing hypotheses (and now, it turned back to research and debating). Voinnet’s papers in Science and elsewhere proved that it was the siRNA which was the mobile signal. Now, that Voinnet’s authority is somewhat dented due to his excessive data manipulations, how reliable are his discoveries?

In fact, Voinnet’s own papers, regardless of the data manipulations therein, carry little experimental evidence for siRNA being the mobile signal. This I was told by Dacheng Liang, a former postdoctoral scientist in the lab of Peter Waterhouse at Queensland University of Technology, Australia:

“In all his early papers, e.g. his Nature Genetics papers Dunoyer et al, 2005 and Dunoyer et al, 2007 Voinnet claimed that 21-nt small RNA, rather than 24-nt long RNA, is the mobile silencing signal”.

As Voinnet himself wrote, his model of 2005 “excludes the participation of 24-nt siRNAs in movement and also predicts that, in the absence of active amplification, the extent of short-range cell-to-cell movement should correlate with the levels of primary 21-nt siRNAs accumulating at the site of silencing initiation.” Also in 2007, Voinnet insisted “neither DCL3 nor AGO4 is required for non–cell autonomous RNAi“. Also in his now corrected paper Dunoyer et al Science 2010, Voinnet reiterated the role of the 21-nt siRNA as the mobile silencing signal, yet he cautiously added in the last paragraph: “Of the 21- and 24-bp siRNA species, we studied only the former in this experiment, because AGO1-dependent RNAi generates a measurable silencing movement phenotype […]. Yet, there is no reason to exclude mobility of DCL3-dependent 24-nt siRNAs, which mediate locus-specific chromatin modifications upon loading into AGO4“.

Why did Voinnet add this clause? Because in the same Science issue, his former mentor Baulcombe published a paper presenting the 24nt siRNA is mobile silencing signal (Molnar et al., 2010). In the EMBO J paper of the same year (Dunoyer et al, 2010, now retracted due to heavy image manipulations), Voinnet suggested that both 21-nt and 24-nt siRNAs were relevant, since his “previous study more specifically identified the DCL4-dependent, 21-nt siRNA as being both necessary and sufficient to mediate non-cell autonomous RNAi, leaving open the possibility that 24-nt siRNAs also can move […] at a distance”.

So basically, Voinnet quietly reversed his original claim of the exclusivity of the 21nt siRNA as the sole mobile signal. Yet this is in comparison a minor issue with his papers, and again, even if one for the time being ignores the data manipulations. Liang explains that Voinnet et al actually never really showed that any siRNA, regardless of its size, was the mobile signal:

“All the genetic factors they found in his 2005 and 2007 Nature Genetics papers are responsible for the generation of silencing signals, or small RNAs. But as to whether these are moving or not, the authors did not show any solid evidence regarding the mobile process, movement rate, or the recipient cells responding to any of the classes of small RNAs. And also, the suc2-P19, suc2-P21 and suc2-DCL4 transgenic experiment in his 2010 Science paper is a key experiment to show the generation of 21-nt small RNAs, but unfortunately they did not give any detailed descriptions or statistic data about those transgenic plants”.

The absence of usable statistical data is apparently a recurring feature in Voinnet papers. Yet this apparently never troubled much the editors or peer reviewers at Science, even when Voinnet’s scientific claims were long disproven, by the research community and even Voinnet himself.

Instead, all Voinnet could show, is that siRNA can move between neighbouring cells though his bombardment experiments with siRNA-coated gold particles. This movement through plasmodesmata however is hardly the same as long-distance silencing though the phloem. Yet according to Liang, Voinnet’s papers never demonstrated “that the labelled siRNA can be detected e.g. in the root if it is bombarded into the leaf or vice versa in the perspective of long-distance mobile signal”.

Liang was therefore already sensitized to Voinnet’s peculiar research when he noticed that Voinnet has modified and re-used a published image in his 2010 Science paper. He then reported his criticisms on his Chinese-language blog.

But, as anyone who follows misconduct cases knows, data integrity is often deemed as a minor or even irrelevant issue, when the faked results are being claimed as reproducible otherwise. This was surely the case with ETH, who described Voinnet’s figures as mere “illustrations”, as if a scientific research paper was a children’s book. CNRS’ attitude was not really better.

So, what about Voinnet’s later discoveries on siRNA as the mobile signal in plant immunity? How reproducible are those?

Voinnet’s former PhD advisor Baulcombe is certainly the right authority to ask here. His lab proved to be the only one, aside of Voinnet’s, to have ever published on siRNA as mobile signal, and in Science no less. To me, Baucombe stated in an email in June 2015:

“I think you will find that several labs have published on movement of siRNA including Waterhouse, Lucas, Kehr, Kragler and Vaucheret is, of course, a pioneer of mobile silencing. There is no postulated concept of an exclusive siRNA signal – there may well be many forms of mobile RNA. We have made that point in our discussion sections and reviews”.

I approached all of the plant scientists Baulcombe named, and some more. If any of them ever reproduced in their labs Voinnet’s (and Baulcombe’s) claim of siRNAs as the mobile signal, they decided to keep this vital information secret from the prying public.

Julia Kehr, professor for molecular plant genetics at University of Hamburg, explained:

“We do not work with siRNAs, but with miRNAs, which can be transported over long distances. We could show that numerous miRNAs can be found in the phloem (Buhtz et al 2008, Plant J 53) and at least two nutrient-deficiency associated miRNAs (miR395 und 399) proved movable through phloem in grafting experiments […]. Voinnet always claimed that miRNAs, unlike siRNAs, are only active locally (e.g., Parizotto et al., Genes & Development 2004), yet in 2009 he admitted in regard to published results for miR399 that at least some specific miRNAs can act as systemic signals in exceptional circumstances (Voinnet, Cell, 2009)“.

Hervé Vaucharet, research director at the INRA Centre in Versailles (with whom the young student Voinnet once interviewed to do his PhD thesis, before deciding to work with Baulcombe instead) did not reply to me on this matter. Friedrich Kragler, group leader at the Max-Planck-Institute for Molecular Plant Physiology in Potsdam, ignored every single one of my emails. Same goes for William Lucas, professor for plant biology at UC Davis, USA and finally, Peter Waterhouse.

Instead, Waterhouse’s collaborators offer some insights. His former postdoc Liang stated:

“I don’t think Peter’s lab has shown that siRNA is the long-distance mobile signal. This is really hard stone to crack. And the evidence from Baulcombe’s 2010 Science looks to me weak if you carefully check the data from the whole paper. The problem is, everyone tends to believe that small RNA is the mobile signal because it’s small and also the key player in gene silencing pathway. Either to prove it or disapprove it is very time-consuming, and might not generate any results. Just as Voinnet lab, they used labelled siRNA to show its mobility, but they just showed it can move to neighbor cells”.

Rosemary White, group leader at CSIRO Black Mountain in Canberra, agreed to publicly explain the science of siRNA and the mobile signal.

White used to be a close collaborator of Peter Waterhouse (Liang’s ex-boss), and surely even Baulcombe would agree that her views on this are relevant:

“Much work, both before and after Voinnet’s published work, showed long-distance movement of a range of molecules (and now, even organelles), in the phloem. I suspect that anything that is in the phloem may be able to move long distances through plants. See, for example, a couple of recent grafting papers (Melnyk et al 2015; Lewsey et al 2015) and other recent papers showing that mitochondria and other plastids can also move across graft junctions (Thyssen et al 2012; Gurdon et al 2016). I have also seen many different GFP-tagged proteins move through phloem across graft junctions. This does not seem contentious at all. There are several other papers showing long distance spread of small RNAs.

We and others have also shown that phloem is quite capable of bidirectional transport. This has long been known for plants with both internal and external phloem, such as the various members of the tobacco and cucurbit families, popular subjects for investigation of phloem transport. But this is true even for Arabidopsis phloem, as shown by us (see Fig. 2 Liang et al 2012) and earlier by Kim et al. 2004 (see Fig. 4), and by several others using smaller fluorescent tracers.

We also showed that siRNA could spread long-distance, but only cell-to-cell (http://www.plantphysiol.org/content/159/3/984.long). We added the caveat that this may be a particular feature of siRNAs, generated from artificial hpRNA, which then target non-endogenous mRNA (GFP, in our case). The most interesting (to me) and novel aspect of our paper was that the signal appeared not to spread via the phloem. We discuss implications of this result. Considering that very many RNAs of different sizes are found in phloem exudates, it would be surprising if phloem-mobile siRNAs were not signals for at least some responses. My own suspicion is that this is only the tip of the iceberg as far as signalling molecules in the phloem”.

White concludes:

“I find it very difficult to trust anything in any of his papers. Fortunately, once the field moves on, there may be diminishing need to refer to Voinnet’s publications”.

What about other peers of Voinnet?

In 2010, the American plant scientists Dan Chitwood and Marja Timmermans wrote a review in Nature about Voinnet’s and Baulcombe’s discovery of 21-24-nt siRNAs as mobile signal: “Small RNAs are on the move”. Is the information presented in their Nature article still reliable?

Chitwood, group leader at Carrington’s Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, wrote to me:

“That a mobile silencing signal exists is not in doubt. The precise identity of that signal, and how its mobility changes in different developmental contexts and which small RNA pathways have mobile activity, is more complicated, and remains an area of active research. These two papers [Dunoyer et al, Science 2010 and Molnar et al., Science 2010 , -LS] are critical for the idea that small RNAs themselves (not precursors, for example) are the mobile silencing signal. Like all papers, the persuasiveness of the results stands on performing correct controls and faith by readers that the figures and images in the paper reflect experimental reality and have not been manipulated”.

Timmermans, formerly at CSHL and now professor for developmental genetics at the University of Tübingen in Germany, explained that her lab, just like that of her new German colleague Kehr, only works on miRNAs and not on siRNA. She however withdrew all her previous quotes to me in regard to Voinnet’s research on mobile signal and his papers.

Timmermans also advised that I contact “for additional information” Detlef Weigel, director of the Max-Planck-Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen. Weigel however admitted: “My own research group largely gave up the topic of small RNAs”, without further explanations.

But surely Shou-Wei Ding, who personally co-authored several papers with Voinnet, including the seminal Science paper on mammalian RNAi, and a review on mammalian siRNA viral defense, can confirm the discovery of siRNAs as mobile signal in plants? Not really, since Ding could only tell me:

“Unfortunately, my lab does not have funding to work on the silencing signal, and thus won’t be able to help you”.

In summary, I obtained despite my long and intensive search not a single shred of reproducibility evidence for siRNA as mobile signal, from all the plant scientists I approached. Everyone can now make their own conclusions on how reliable Voinnet’s discoveries and what exactly the point of saving his papers was.

What about that of RNAi in mammals, also published in Science (Maillard et al., 2013)? The scientist, who openly criticized this paper and the corresponding Letter in Cell Reports by Ding and Voinnet, was then accused by Voinnet of masterminding the PubPeer smear attack against him. The ETH investigative commission apparently deemed this utterly false and bizarre conspiracy claim credible enough to make it public, uncommented.

Is the nightmare finally over? Many in plant sciences and wider academia prefer to dismiss Voinnet as a case of individual dishonest scientist. To them, science has self-corrected itself, time to forget and move on. Noone involved was sacked (as it seems), yet they all are supposed to have learned their lesson.

Voinnet case is not a stand-alone incident of a dishonest scientist. It is also a failure of the entire plant science community, who even now are largely too scared to air their dirty laundry. Indeed, they have every reason to be: Voinnet and every single one of his main co-authors worldwide are still in their influential faculty positions.

What we are now witnessing is not a self-cleaning, but a chronic failure of science and of academic institutions, like:

- French research center network CNRS, who re-defined what scientific fraud was to ensure Voinnet could not have committed it, kept the entire investigation totally secret, and retained his right hand Patrice Dunoyer in his job as IBMP research group leader.

- Swiss elite university ETH Zürich, who decided to support Voinnet after their own overtly benevolent investigation and failed to even formally interview his ex-team member and presently ETH professor as well, Constance Ciaudo.

- British University of East Anglia, who already trice refused my FOIA request about their investigation into Voinnet’s manipulated PhD thesis. Since I know from reliable sources that this investigation did happen, I must assume the university either buried it, or already acquitted Voinnet against all evidence.

- Elite journals like Science, PNAS, Genes & Development, RNA and others, which unscrupulously allowed Voinnetting to happen. Their editors obviously decided that a research paper can still have its full value, despite deliberate data manipulations with the very likely intention to deceive. Yet by far the worst offender in this regard is Cell Press, which quietly keeps on ignoring all evidence for data manipulation in 3 papers in Cell (Voinnet et al, 1998: Voinnet et al, 2000, Chow et al, 2010, and one paper in Molecular Cell (Garcia et al, 2012). It seems for the Elsevier-owned Cell Press and the EiC Emilie Marcus, the Voinnet scandal either never happened or is long forgotten.

Some publishers, like PLOS and EMBO Press were brave enough to retract Voinnet papers beyond or even against the recommendations of ETH commission. Especially the European research society EMBO, initially reluctant to get involved into the Voinnet affair, acted most exemplary afterwards. Following their own investigation, EMBO withdrew the Gold Medal from this ETH professor and French Academy of Sciences member.

The way how Voinnet misconduct has been dealt with, makes a dangerous precedent. Voinnetting of manipulated papers can soon become a standard rather than exception, and zombie scientists will multiply.

Pingback: Olivier Voinnet, the new Dreyfus? – For Better Science

Pingback: Inspector Voinnet, Wollman in fraud-overdrive, and Farewell to Jessus – For Better Science