A scientist from Portugal contributes this anonymous guest post about the precarious position of non-tenured researchers in Portugese academia, and why the government and the ruling academic elites want these masses to be in such miserable situation, where they can be easily exploited. A situation you might recognise from your own country.

The author is also a sleuth, under the PubPeer pseudonym Orthopyxis integra they previously contributed this article about papermill fraud:

Pest Management

” I have been receiving too much of these types of papers lately and I think we all are wasting our time with made up science” = Orthopyxis integra

Even Sonia Melo failed to obtain a professorship in Porto, so tough is the situation in Portugal. Although in her case, the reason is public shame due to massive fraud, a retraction, and a revoked EMBO award. Peter Jordan almost reached retirement age without having made it to full professor in Lisbon, his other handicap is being a foreigner. Patricia Madureira, the wife and coauthor of the sacked fraudster Richard Hill, and PhD mentee of another sacked fraudster, Eric Lam, managed to hold on to her job as group leader at University of Algarve. But also she didn’t make it to proper professor, only to an “invited” one.

I added several Boxes with examples of other successful scientists in Portugal. For your inspiration!

Academic precarity in Portugal

by Orthopyxis integra

In Portugal more than 95% of all research activities are carried out under precarious labour conditions, by undergraduate and PhD researchers employed under a variety of temporary contracts, often with limited or no benefits, and no access to a career. Several mechanisms are used to maintain this situation, including never-ending “highly competitive” national calls for temporary research positions, the creation of university-affiliated public foundations operating under private management and umbrella research centres that hire researchers on the margins of the public sector. Regarding teaching staff in higher education, over 40% of professors hold non-permanent contracts. Those with permanent positions are often stuck at the rank of assistant professor, with little or no prospect of promotion, with full professors, who represent less than 10 % of permanent positions, holding most of the institutional power. This is compounded by the fact that higher education institutions are kept chronically underfunded and understaffed, with researchers expected, or compelled, to teach under the threat of contract termination or non-renewal. This is the story of how we get here.

Zombie scientist Sonia Melo awarded by AstraZeneca

Sonia Melo is back, and not to be messed with. The Portuguese zombie scientist is responsible for a number of papers with manipulated data (only one was retracted, Melo et al, Nature Genetics, 2009), saw her EMBO Young Investigator funding withdrawn in 2016, but was whitewashed and reinstalled by her employing institute Instituto de Investigação e…

The making of the system

The start of this story can be situated in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the preceding decade, Portugal’s public higher education system underwent a massive expansion alongside the country’s democratization. A system that had been limited to universities in Coimbra, Lisbon, and Porto (four to five over time) rapidly expanded to around forty public higher education institutions (IES, Instituições de Ensino Superior), including universities and polytechnics, spread throughout the country. This expansion was accompanied by a strong push to democratize academia. Under the toppled dictatorship, the government exercised strict control over pedagogical and administrative matters, including the appointment and dismissal of rectors, and there was broad consensus in the early democratic period that this had to change. The 1988 University Autonomy Law (Lei da Autonomia das Universidades, LAU) institutionalized participatory governance by creating assemblies and senates and granting IESs administrative, financial, pedagogical, and scientific autonomy, while establishing internal accountability. The rector remained the highest authority, but was now elected by the University Assembly, which included students and non-teaching staff, though dominated by professors, while the University Senate retained key decision-making powers.

Portugal joined the European Economic Community in 1986, accelerating its integration into European political, economic, and educational frameworks and making alignment with European scientific standards a priority. At the time, R&D was largely confined to about a dozen State Laboratories (Laboratórios do Estado, LEs), focused on applied research for national needs, with limited investment on fundamental research. This had to change. Academic careers also required modernization. The system followed a hierarchical chair model in which academics typically began as Monitores (Teaching assistants), often while still students, then progressed to Assistentes (Lectures) after the Licenciatura, then to Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and finally Professor Catedrático (Full Professor), usually within the same institution. Advancement depended on formal public examinations (provas): teaching aptitude (PAP), doctorate, and habilitation (agregação). Because vacancies were tightly controlled, most academics remained in lower ranks all their careers, while Catedráticos wielded disproportionate power. Proposed reforms included abolishing the Monitor and Assistente stages, replacing PAP with Master’s degrees, redefining the doctorate as a genuine academic qualification, and requiring PhD completion and demonstrated research independence for entry into an academic career.

A German in Lisbon

Peter Jordan is exactly the kind of scientist Portugal needs.

The 1980ies were also a time of growing neoliberalism, and these reforms unfolded just as the state began to step back from long-term commitments to funding and employment stability in higher education. In this context, the 1988 LAU, while consolidating democratization and openness, also worked as something of a “poisoned gift.” Universities were given financial autonomy at a time of shrinking public funding. State transfers soon became insufficient even to cover salaries, forcing institutions to figure things out on their own. Attempts to shift costs onto students through tuition fees in the early 1990s did not go well, triggering massive nationwide protests. As a result, while public higher education in Portugal is not free, tuition fees remain far from sufficient to cover the real costs of education.

It was in this context that the Scientific Research Fellowship Statute (Estatuto do Bolseiro de Investigação Científica, EBIC; Law 40/89) was approved in 1989. EBIC formalized research fellowships that had long existed as maintenance subsidies for students and graduates but lacked a legal framework. It was presented as a way to protect fellows’ interests, but from the outset, it functioned as a mechanism to bypass the country’s labour laws. As nationally and European-funded research expanded, projects required labour, and the legal status of bolseiro supplied essential workers without employment rights. Because fellowships were legally defined as “scientific training” rather than work, host institutions were not considered employers and bore none of the obligations of employment law. Fellows were covered only by a voluntary, low-level social security regime calculated at the minimum wage, received no unemployment benefits, paid leave, holiday or Christmas pay, and had very limited sick and parental rights. Still, contracts demanded exclusivity, creating bound serfs for the emerging national R&D system.

Richard Hill, the man even gels are afraid of

Get ready to meet Dr Richard Hill and his amazing jumping blots. Just don’t stare, or you’ll get hurt.

From the early 1990s on, IESs and even the old LEs became increasingly populated by bolseiros working on research projects under different fellowship schemes. Regular annual calls for Master’s and PhD fellowships were introduced at this time. The pay was not bad, enough to cover rent, live reasonably well, and often fund research stays abroad. Mobility, mainly within Europe, was strongly encouraged, and many fellowships fully supported completing graduate degrees outside Portugal. These opportunities for internationalisation and participation in research networks were exciting for many young people who had the chance to pursue research they were passionate about, often in leading institutions abroad. In your twenties you do not worry much about illness or retirement anyway, and fellows were led to believe that if they were good enough, an academic career would follow. Carrot and stick: the bolsa was the stick, and the carrot was the promise of future security and a decent career.

During the 1990ies science gained such prominence in Portugal that it was assigned its own ministry, with Catedratico José Mariano Gago as its first minister, the evil genius considered to be the architect of the modern Portuguese R&D system. Gago would go on to serve a total of 13 years in government (1995–2002 and 2005–2011), longer than any other minister in democratic Portugal, moving straight from the top ranks of academia into government, and later back to academia. A new funding agency – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) was created in line with EU research policy, emphasizing competitive funding. To access this funding, IESs were required to organize Research Units (Unidades de I&D, UIDs), which would then be subject to external evaluation and ranking. FCT also became the sole manager of national competitive PhD fellowship calls, which were scaled up to boost the country’s number of PhD graduates, in line with EU targets.

Meanwhile, many of the early bolseiros were finishing their PhDs and IESs, and LEs were not opening permanent positions. To keep the party going, FCT’s solution was to start a program of postdoctoral fellowships – bolsas, not contracts. After all, if in other countries researchers pursued postdoc positions after PhD, it was assumed that Portugal should replicate this model. And after you’ve finished a three-year postdoc? Another three-year post-doc, and then another one…

BOX 1

João Conde made it to full professor, at Universidade NOVA de Lisboa. He was seen on Rahimi et al 2021 together with the Ukrainian cheater Taras Kavetskyy and other papermill customers from all over the world.

Taras Persidskyy and Arik of Negev, Shahed Hunters

“He has embarked on a path of unacceptable slander, not only against me, but also against my colleagues (Prof. Oleg Smutok, Prof. Arnold Kiv, Prof. Vladimir Solovyov). We have all the necessary evidence to bring Leonid Schneider to justice for slander and moral turpitude.” – Taras Kavetskyy.

Here is Professor Conde using Iranian papermills, where cell lines have signed informed consent:

Hamed Nosrati , Farzad Seidi, Ali Hosseinmirzaei , Navid Mousazadeh , Ali Mohammadi , Mohammadreza Ghaffarlou , Hossein Danafar , João Conde, Ali Sharafi Prodrug Polymeric Nanoconjugates Encapsulating Gold Nanoparticles for Enhanced X‐Ray Radiation Therapy in Breast Cancer Advanced Healthcare Materials (2022) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202102321

Conde is working with real papermill professionals – Michael Hamblin, Milad Ashrafizadeh and Pooyan Makvandi:

Joana Lopes , Daniela Lopes , Miguel Pereira‐Silva , Diana Peixoto , Francisco Veiga , Michael R. Hamblin , João Conde , Claudia Corbo , Ehsan Nazarzadeh Zare , Milad Ashrafizadeh , Franklin R. Tay , Chengshui Chen , Ryan F. Donnelly , Xiangdong Wang , Pooyan Makvandi , Ana Cláudia Paiva‐Santos Macrophage Cell Membrane‐Cloaked Nanoplatforms for Biomedical Applications Small Methods (2022) doi: 10.1002/smtd.202200289

The last author Ana Cláudia Paiva‐Santos is now assistant professor at University of Coimbra, also thanks to papermilling (see PubPeer), and she knows all he right providers. This, with Navid Rabiee and Ehsan Nazarzadeh Zare (whom you met above), was retracted, it contained massive forgeries and purchased citations:

Roham Ghanbari , Ehsan Nazarzadeh Zare, Ana Cláudia Paiva-Santos, Navid Rabiee Ti3C2Tx MXene@MOF decorated polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for the remediation of heavy metals ions and desalination Chemosphere (2023) doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137191

The retraction from September 2025 mentioned “an unauthorised authorship change […] with two authors being deleted“. Previously, Paiva-Santos’s paper with Indian fraudsters, Corrie et al 2024, was retracted in November 2024 for “several image duplications“. Paiva-Santos also orders from Pakistani papermills, this was corrected:

Mariam Aslam, Kashif Barkat , Nadia Shamshad Malik, Mohammed S. Alqahtani , Irfan Anjum, Ikrima Khalid, Ume Ruqia Tulain, Nitasha Gohar, Hajra Zafar, Ana Cláudia Paiva-Santos, Faisal Raza pH Sensitive Pluronic Acid/Agarose-Hydrogels as Controlled Drug Delivery Carriers: Design, Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation Pharmaceutics (2022) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14061218

Kashif Barkat, Mahmood Ahmad, Muhammad Usman Minhas, Ikrima Khalid, Nadia Shamshad Malik Chondroitin sulfate-based smart hydrogels for targeted delivery of oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer: preparation, characterization and toxicity evaluation Polymer Bulletin (2020) doi: 10.1007/s00289-019-03062-w

Kashif Barkat , Mahmood Ahmad, Muhammad Usman Minhas, Ikrima Khalid , Bushra Nasir Development and characterization of pH‐responsive polyethylene glycol‐co‐poly(methacrylic acid) polymeric network system for colon target delivery of oxaliplatin: Its acute oral toxicity study Advances in Polymer Technology (2018) doi: 10.1002/adv.21840

The MDPI correction from December 2024 informed that “Due to a technical error during the preparation of the manuscript, images from a different study conducted by the same research group were mistakenly included“. You can read about Muhammad Usman Minhas here:

Queen’s University Belfast fights Welsh Terrorism

“your scatter gun approach has undermind a process that is undertaken confidentially […] It is sad that you are determined to undermine people’s reputations in the way you do.” – Queen’s University of Belfast to Sholto David.

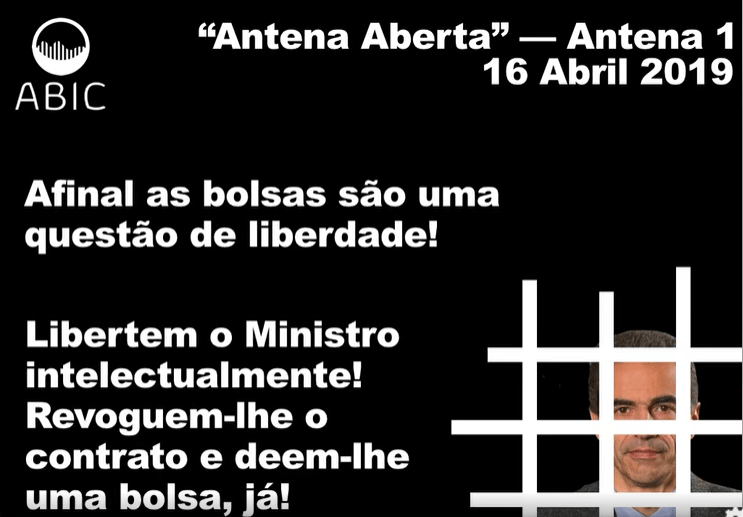

By the mid-2000s, several waves of PhD graduates had piled up in the system as postdocs. Fellowships were no longer as attractive as they had been. Opportunities for research stays abroad were becoming harder, and stipends had lost much of their value after years without updates, inflation, and the economic adjustments that followed Portugal’s entry into the Eurozone. Protests began to emerge, along with increasing public awareness of the precarious situation faced by these researchers. In 2003, bolseiros even created their own association – Associação dos Bolseiros de Investigação Científica (ABIC)- to make their voices heard. FCT responded according to its modus operandi, it opened a new competitive call for temporary research positions.

The Ciência 2007 program offered just over a thousand fixed-term contracts with full employment benefits. It was marketed as an opportunity for the “best and brightest” to run independent projects in Portuguese institutions, with salaries roughly at assistant-professor level. Thousands of postdocs applied, a few obtained a contract, most did not. The program also attracted Portuguese PhDs living abroad and even some foreign researchers. These awardees were led to believe that the contracts would open the door to permanent positions. And what happened when the contracts ended? Right! Nothing happened.

However, the initiative was so effective in gaslighting the academic precariat that FCT institutionalized it, launching in 2012 the Investigador FCT program. These calls offered 300–400 fixed-term contracts per year across three levels –Auxiliar, Principal, and Coordenador– based on the applicant’s experience. FCT also pushed for a legal framework (Law 28/2013), formalizing a precarious, competition-based research career structure. This created an annual ritual in which thousands of postdocs competed for a few hundred contracts. The vast majority remained dependent on bolsas, but now the blame was on them for not being “good enough” to secure a contract. FCT had effectively become a temp agency, placing both bolseiros and fixed-term researchers in IESs and LEs to cover gaps institutions were not allowed to fill with regular employment.

Box 2

The associate Professor with a habilitation, José M.F. Ferreira “did his entire academic career at University of Aveiro“, as his CV informs. Sadly, his “collaboration” with people like the Egyptian papermiller fraudster Essam R. Shaaban came way too late to make the 75 year old Ferreira a full professor!

Ashutosh Goel, Essam R. Shaaban , J.B. Oliveira , M.A. Sá , Maria J. Pascual, José M.F. Ferreira Sintering behavior and devitrification kinetics of iron containing clinopyroxene based magnetic glass-ceramics Solid State Ionics (2011) doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2011.01.009

Here the papermill mistyped his name, poor “Joés”:

Essam R. Shaaban , Ishu Kansal , S.H. Mohamed , Joés M.F. Ferreira Microstructural parameters and optical constants of ZnTe thin films with various thicknesses Physica B: Condensed Matter (2009) doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2009.06.002

Dysdera arabisenen “Fig 1. 331, 415, 508, 605, 695 traces have near-identical noises”

It is clear by now that two systems had been coexisting for some time within Portuguese IESs and LEs. One consisted of a shrinking core of permanent staff, who had never experienced job insecurity. They typically entered as assistants or junior researchers, completed a PhD, and gained automatic promotion to assistant professor, but further career progression had largely stalled due to budget cuts. The other system consisted of an ever-growing precariat, surviving on successive bolsas, temporary contracts, and short-term teaching assignments, often interspersed with unprotected unemployment. This precariat conducted not only research, but often informal teaching and administrative work, and institutions could not function without them. A perverse relationship developed between the two groups. Permanent staff relied on the precariat to maintain research output and improve the former’s CVs, while fearing that the highly qualified temps might eventually secure permanent positions, which would threaten their dwindling prospects of career progression. Precarious researchers, in turn, had to remain in good terms with the permanent staff, because they really did not have any power or autonomy within the institutions, performing informal labour in the hope of one day entering the official academic ranks. In this crazy dysfunctional arrangement, a small number of Associate Professors, and especially Catedráticos, accumulated multiple top managerial positions and concentrated their power, frequently demanding authorship credit in publications and asserting dominance over research output. Some effectively became proper despots of their research centres and IES departments.

Meanwhile, Mariano Gago (yes, that guy again), in his relentless pursuit of a neoliberal, scientific autocracy, quietly pushed a legal framework that finished off with what remained of democratic governance in the IESs. Under the RJIES (Regime Jurídico das Instituições de Ensino Superior – Legal Framework for Higher Education Institutions, approved in 2007), rectors and faculty presidents were no longer directly elected by school assemblies but chosen by newly created General Councils (Conselhos Gerais, CGs). About two-thirds of CG members are elected representatives of professors, researchers, staff, and students (in uneven proportions); the remaining third are “external personalities of recognized merit”, whatever that means. These illustrious outsiders are selected by the internally elected members, in processes that have long been criticized for their opacity and dependence of personal and political patronage. CGs then elect the rector (or faculty president), who will appoint the executive team: vice-rectors, vice-presidents, and the management council. Afterwards, CGs are left with supervisory and advisory roles, meaning the only formal check on executive power is the body that elected it. Senates and assemblies were downgraded to consultative status, or abolished entirely. The Portuguese government continued to invoke academic “autonomy” to justify non-interference while effectively eliminating internal democratic regulation. RJIES also pushed IESs to adopt strategic plans, performance indicators, efficiency targets, and managerial evaluation systems. It allowed IESs to become public foundations under private law (fundações públicas com direito privado), create private institutes, or establish hybrid semi-private units, moves widely seen as backdoor privatization of higher education.

It is an understatement to say that the RJIES has been widely hated and protested since its approval. Yet all attempts to revise or revoke it have so far been unsuccessful. Still, the life’s work of Mariano Gago was considered so astonishing that after his death in 2015 the government declared his birthday, 16 May, as the National Day of Scientists. No kidding, the man is still considered almost like a saint.

The debacle and descent into madness

Since schemes meant to sidestep labour laws always tend to be abused, IESs and LEs, perpetually short on staff and budget, began using the EBIC to fill non-academic positions with bolseiros. Because EBIC covered a wide variety of grant types, requiring different education levels, from secondary-school diploma to university degrees, the sky was the limit. If a research plan could be drafted, a supervisor appointed, and some sort of “research project” funds allocated, administrative workers, technicians, and all kinds of support staff, ranging from bricklayers to gardeners, could be hired as bolseiros. Soon, the practice expanded beyond academia. Several governmental departments, exploiting similar loopholes, also began hiring bolseiros, and eventually, even private companies joined in. The country became so enthusiastic about science that everybody could end up a researcher.

This went on for years until it caused a somewhat national scandal after an investigation by the public broadcaster RTP was aired in 2016, forcing the government to address the issue. PREVPAP (“Programa de Regularização Extraordinária dos Vínculos Precários na Administração Pública” or “Extraordinary Program for the Regularization of Precarious Employment in the Public Administration”, Law 112/2017) was approved to convert precarious public-sector employment, including bolseiros, into stable contracts in line with national labour laws. In most areas of the public sector, including LEs, where staff had not been replenished for years, the initiative was welcomed because these workers were clearly needed. The program ultimately regularized more than 17,000 positions across several sectors. However, when it came to the IESs it was a totally different story.

By this time, ten years after the RJIES came into force, the council of rectors (CRUP), who had basically turned themselves into totalitarian lords of their academic fiefdoms, were absolutely outraged by the imposition of PREVPAP. According to these entitled creatures, PREVPAP didn’t safeguard “merit-based recruitment,” which they claimed was essential for academic and research careers. They kept insisting that precarious researchers and professors didn’t fit the definition of “permanent needs of the institution” required for regularization, because in their minds these workers should be precarious anyway. High turnover, they argued, is necessary to keep the system running. All this would be laughable if it weren’t so infuriating, considering that most of these high achievers had entered academia under the old system and had never had a single day of job insecurity in their lives, while most of the precariat had spent decades jumping from one competitive call to the next. The government went along with this circus, largely thanks to their scheming science minister, the catedrático Manuel Heitor, always ready to do the bidding of his rector buddies. As a result, within the science and higher-education sector, of the roughly six thousand PREVPAP applications submitted, only about 22 percent were approved. For teaching staff and researchers, things were even worse, with just about 13 percent obtaining stable contracts through the program.

These exclusions led to a wave of legal challenges, with many applicants filing court cases alleging violations of PREVPAP and national labour laws. Precise national figures for these court actions are difficult to obtain, but news reports often mention dozens or even hundreds per institution. Courts mostly ruled in favour of the workers, forcing institutions to integrate many PREVPAP candidates they had previously rejected, including researchers and professors, and in some cases to restore full salary and seniority rights. This likely cost the IESs millions and demonstrated that, although rectors could manoeuvre the government, they could not override the independent courts of the Portuguese Republic.

FCT reacted to this mess in its usual way, immediately rolling out a framework to keep the precariat hooked. It pushed for the approval of Law 57/2016 (commonly known as DL57), which placed all active postdocs with more than three years of FCT funding -the bulk of Portugal’s PhD precariat- under temporary contracts, rather than granting them permanent positions in institutions, as PREVPAP had demanded. Most researchers who had previously held contracts through the Ciência 2007 and Investigador FCT programs were eventually integrated into their host institutions, often after lengthy court proceedings. On paper, DL57 stated that these new contracts should convert into permanent positions after six years, giving researchers hope and discouraging litigation. In practice, however, IESs interpreted DL57 as they saw fit, deploying a range of strategies to avoid creating the required permanent positions, including dubious performance evaluations timed to terminate contracts early, and exploitation of legislative loopholes.

Box 3

Meet the catedrático Armando J. L. Pombeiro, Full Professor Jubilado at Universiyt of Lisbon. Even today, this old rascist prides himself being “Distant Director at the RUDN University (Moscow)“, a job he obtained thanks to the Spanish papermilling ork Rafael Luque. In 2022, after russia attacked Ukraine in a full scale genocidal war, Pombiero travelled to Moscow to support his dear friends at a conference (read April 2023 Shorts, and see archived announcement). He still sits on the editorial board of a russian journal.

But Pombeiro has other contacts to provide him with papers. For example with the Polish Photoshop artist Tomasz Sliwinski, read about the latter here:

Would you in Lodz?

“Forgeries of this calibre make me think anything ever published by Sliwinski, Skorski and their associates is made up. In an ideal world, hundreds of articles by these people showing just tables and graphs should get retracted ” – Aneurus Inconstans

Here a common study:

Luís M T Frija, Epole Ntungwe, Przemysław Sitarek, Joana M Andrade, Monika Toma, Tomasz Śliwiński, Lília Cabral, M Lurdes S Cristiano, Patrícia Rijo, Armando J L Pombeiro In Vitro Assessment of Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Cytotoxic Properties of Saccharin-Tetrazolyl and -Thiadiazolyl Derivatives: The Simple Dependence of the pH Value on Antimicrobial Activity Pharmaceuticals (2019) doi: 10.3390/ph12040167

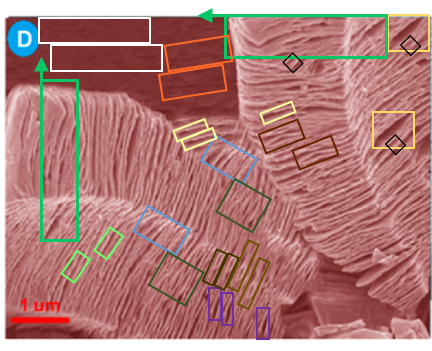

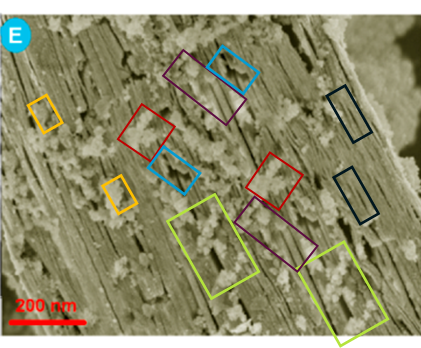

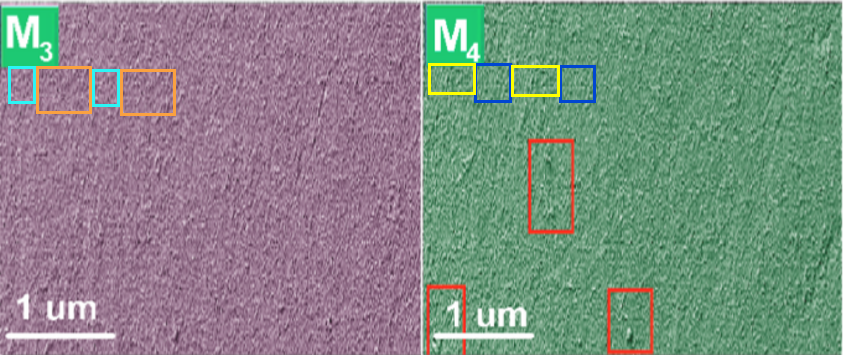

I labelled most of them with boxes of same color, but there are many more.”

As the first wave of DL57 contracts began to expire, pressure from researchers and several unions mounted on the government to enforce the law. The new science minister succeeding Manuel Heitor, Elvira Fortunato -another catedrática and a science celebrity in Portugal, apparently perfect prerequisites for a government job- infamously declared, “If we integrate everyone into the permanent staff, we kill science.” This outrageous remark quickly became a symbol of the struggle against scientific precarity and was reclaimed in protests under the slogan “it is precarity that kills science.” Fortunato responded to the pressure – you can guess how – with yet another competitive call, FCT Tenure, offering 1,000 positions to more than 5,000 researchers about to lose their jobs. Of course, the call was not specifically for these soon-to-be-unemployed researchers who had been in the system for ages. Instead, it was opened internationally to “hire the best and the brightest,” with a deliberately painfully complicated funding model, leaving it unclear what career path these contracts correspond to or whether they are genuinely permanent positions, or just another reincarnation of extended precarity.

This drama is presently unfolding. Some IESs appear to have learned a lesson from earlier litigation and are choosing to open permanent positions for DL57 researchers. Many others, however, continue to resist, and a new wave of court cases is happening right now with the support of several unions. This time, the claims go beyond violations of labour law: researchers are alleging discrimination and violations of their civil rights due to the denial of access to public employment, a right that is explicitly protected under the Portuguese Constitution. These cases are now moving through the lower courts and beginning to reach the Supreme Court.

With the scandals surrounding the misuse of EBIC, pressure mounted to revoke this dreadful piece of legislation. This, of course, has been unsuccessful so far.

In 2019, the sulky and petulant Manuel Heitor argued on several occasions that “research fellows should not have employment contracts,” and that grants were the best instrument to guarantee “intellectual freedom”, unlike employment contracts such as those held by faculty members. In response, ABIC made a funny video where they called for Manuel Heitor to be liberated from his own secure, cushy professorship and placed on a bolsa, so that he too could experience such enlightened freedoms.

FCT did end its programme of postdoctoral grants, but PhD candidates have continued to be funded under the EBIC. Bolseiros still exist, including postdoctoral fellows, although in smaller numbers and mostly tied to research-project funding. Meanwhile, FCT has been ramping up the numbers of PhD fellowships, which now exceed 7,000, with IESs pushing hard to increase it even further. A growing number of cases has been reported in which IESs use these PhD fellows to cover teaching gaps.

To replace its now-defunct postdoctoral grants, FCT introduced a new, lower-paid “Junior Researcher” category within its call for researchers, now renamed CEEC — Concurso Estímulo ao Emprego Científico, which can be translated as “Competition / Incentive for Individual Scientific Employment.” Yes, they don’t exactly provide scientific employment; they “stimulate” it. The call runs annually as an international competition, with candidates applying for six-year contracts individually, just like the old FCT schemes. It awards roughly 300–400 contracts per year to around 5,000 applicants, turning it more into a lottery than a selective hiring process. Because awardees could technically claim employment rights after the six-year contract, many IESs began imposing limitations on hosting applicants. In response, FCT created new schemes in which institutions, not individual candidates, apply for hiring slots. Once quotas are awarded, institutions open international calls, select candidates, and manage the contracts. To prevent these hires from claiming permanent positions in the IESs, these contracts are mostly channelled through legally separate “umbrella” foundations, associations, or institutes operating under private-law rules, on the margins of the public sector.

These sort-of-private entities have been a feature of the IESs ecosystem for some time, even more so since the RJIES came into force, but their numbers have absolutely exploded since 2017, with FCT’s enthusiastic blessing. Currently, on top of 8 LEs and 40 IESs, the Portuguese R&D system includes 313 UIDs, and in a tangled mix of UIDs, there are 41 Associated Laboratories (LAs), 41 Collaborative Laboratories (CoLabs), and 26 Technological Interface Centres, and various other types of public-private enterprises and non-profit private institutions, all supposedly participating in research, technological development, or science communication. It’s such a complex and convoluted system, it makes your head hurt. These entities almost never correspond to any new physical infrastructure; they’re basically administrative mash-ups of pre-existing units.

For example, LAs usually combine 2, 3, or 4 UIDs, housed in their respective old university departments. When an LA is created, it automatically includes all PhDs of those UIDs, with permanent contracts or not, consent or not, capitalizing on their CVs for FCT evaluation. These members are then required to add the LA to their affiliation and acknowledge its funding, which often never benefits them directly. Nothing new is created; everything is just rebranded and recycled. Why? To tap FCT funding, boost metrics for project applications, and serve as vanity projects for high-ranking faculty, all while depriving many researchers and teaching staff of a career. Researchers hired in these fantasy entities with FCT funding, will work at the IES, doing both teaching and research. Which career path these hires correspond to is uncertain, as is their long-term stability. The calls for applications are so murky and misleading that some researchers believe they were being hired for permanent positions at the IES, only to discover, after signing, that their contracts are tied to an LA or CoLab, which itself has an expiration date dependent on governmental/FCT renewal. When this entire house of cards collapses, and it inevitably will, we can expect a renewed era of chaos and litigation in Portuguese science.

Box 4

Natália Cruz-Martins, affiliated professor at University of Porto and University of Minho, also managed to stay employed in Portuguese academia, thanks to papermilling. Her dealers are Abhijit Dey and Javad Sharifi-Rad, some of that is evidenced on PubPeer. Read about Dey’s and Sharafi-Rad’s papermill business here:

I have almost 100 manpower with me at any time

“WE DONT PAY FOR PAPERS. YOU MUST KNOW THAT THESE BEST IN THE PLANET JOURNALS GO THROUGH RIGOROUS PEER REVIEW” – Abhijit Dey, papermiller

But not just Dey whose services Cruz-Martins uses, this here suffers from tortured phrases, according to Alexander Magazinov:

Gitishree Das , Han-Seung Shin , Gerardo Leyva-Gómez , María L. Del Prado-Audelo , Hernán Cortes , Yengkhom Disco Singh , Manasa Kumar Panda , Abhay Prakash Mishra , Manisha Nigam , Sarla Saklani , Praveen Kumar Chaturi , Miquel Martorell , Natália Cruz-Martins , Vineet Sharma , Neha Garg , Rohit Sharma , Jayanta Kumar Patra Cordyceps spp.: A Review on Its Immune-Stimulatory and Other Biological Potentials Frontiers in Pharmacology (2020) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.602364

“The presence of cordycepin (3′-deoxyadenosine) and 2′-deoxyadenosine in C. sinensis was characterized by using atomic attractive reverberation (NMR) and infrared spectroscopy (IR) (Shunzhi and Jingzhi, 1996).”

In 2023, Cruz-Martins and a fellow papermill user, Christophe Hano, acted as editors of an MDPI special issue of Plants, where they contributed 3 out of 9 papers (the rest was papermill trash also).

Epilogue

Why is there such an obsession with keeping most of scientific workers and educators in the Portuguese R&D and higher‐education system in a permanent precarity? Why were so many thousands pushed into a callous and exploitative system, doomed to a lifetime of precarity, jumping from one competitive call to the next, only to be treated as expendable and replaceable, without consideration for their skills or the millions the country invested in their training? In my view (an opinion shared by many), it comes down to power and control: maintaining power in the hands of those who already hold it.

Portuguese academia is rooted in a deeply hierarchical tradition in which catedráticos historically held an almost feudal level of authority. Despite the democratizing efforts of the 1970ies and 1980ies, this structure never really changed. There is also a deeply rooted culture of deference toward catedráticos and a long-standing tradition of cozy relationships between academia and political power. Portugal’s former dictator, António Salazar, was a catedrático; our current President, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, is also a catedrático. The country has a long history of pulling politicians, and despots, from the upper ranks of academia. It is common for top academics to move in and out of government, switching between ministerial roles and comfortably sliding back into their senior academic posts. This revolving door is especially visible in the ministries and agencies responsible for higher education and science policy, whose leaders almost always come straight from top positions on universities or polytechnics. Former rectors, deans, polytechnic presidents, and research-unit directors routinely step into positions where they are expected to regulate the very institutions and colleagues they were working with the week before. Meanwhile, Portugal’s democratically elected government has very limited direct control over the internal governance of IESs, which have become little autocratic fiefdoms, all while costing taxpayers billions every year. And let’s be clear, despite all the talk about “private governance” or “competitive funding” Portuguese higher education and R&D would collapse without sustained public funding. Precarity ensures that most researchers and professors remain dependent, replaceable, and politically weak, and that, in turn, allows a small group of senior academics, who in practice operate in a mafia-style network, to retain control over funding, careers, governance, and the entire direction of the system.

And don’t think this is happening without protests. The precariat initially took some time to mobilize, convinced that with harder work they might eventually reach a permanent position. But over time, they did organize, and the struggle over the past ten years has been relentless. Every time there is an event meant to showcase the wonders of Portuguese science, often attended by ministers and other government officials, groups of researchers and union representatives gather outside to protest precarious working conditions. These demonstrations frequently attract more media attention than the supposed “wonders” of science being celebrated inside. There have been a few large-scale protests involving thousands of researchers. Unions have dedicated departments and even teams of lawyers to support precarious researchers through multiple waves of litigation. Some precarious researchers have even become union leaders themselves. There have been victories: some researchers have secured permanent positions or at least more stable contracts. However, the essence of the system itself remains largely unreformed. Every success is quickly offset as the system finds new ways to maintain the status quo.

Box 5

This is how Portugese catedráticos spend their time. Below on the left is Carlos Nieto de Castro, emeritus professor at University of Lisbon. On the right is the infamous Ashutosh Tiwari, owner of the scamference business IAAM:

Source IAAM“ (University of Lisbon)

The picture is from the now deleted February 2023 press release by University of Lisbon (archived here), which was full of praise for IAAM. Nieto de Castro was celebrated for having been “elected a Fellow of the International Association for Advanced Materials (IAAM), in recognition of his contribution in the field of Thermophysics of fluids and materials with energy applications“. We were told that he also was “the second Portuguese researcher to obtain this distinction“. Nieto de Castro went to Tiwari’s “Advanced Materials World Congress” in October 2022 to receive his fake award.

As I reported in July 22023 Shorts, Nieto de Castro accidentally replied to me, meaning to write to his university colleagues only (translated):

“A surprise for me. I don’t know this journalist, and I don’t know what his intention is (fishing?).

I contacted the target, director of IAMM (Professor Ashutosh Tiwari, informing him of this email, and asking for his comments. As soon as I receive them, I will forward them for your information)

However, links to the organization’s page are:

https://www.iaamonline.org/fellow-of-iaam

The only other Portuguese who is an IAMM fellow, is on the previous page, and is Professor Rodrigo Martins, from Universidade Nova de Lisboa, and from CEMOP.

I am at your disposal to provide any clarification.

I would appreciate your maximum description [sic!], as it involves my name and that of FCUL, until the complete clarification of this matter.

Academic greetings

Carlos Nieto de Castro”

Here is the 2020 announcement of Professor Rodrigo Martins’s IAAM fellowship, which his university simply copy-pasted from an email by Tiwari. The IAAM letter was posted there, also.

Donate!

If you are interested to support my work, you can leave here a small tip of $5. Or several of small tips, just increase the amount as you like (2x=€10; 5x=€25). Your generous patronage of my journalism will be most appreciated!

€5.00

João Conde, quite a promising genius. In a country where most researchers and professors remain on precarious contracts for their entire careers, he managed to become a full professor in his 30s or 40s. He should probably advise the rest of us on how he pulled it off. Maybe he could lecture on how to build strong and productive partnerships with papermills. With the relentless push to publish in Portugal, where researchers are largely evaluated by h-index and citation counts, and the absolute lack of oversight, with no independent authority to oversee and punish misconduct, this becomes the most efficient path forward. Embrace international scientific fraud.

He has also been very active in the press, publishing opinion pieces on several topics related to science in Portugal, mostly calling for more funding—after all, someone has to pay for the paper-mill products and hire more temporary labor to keep the system running.

https://www.publico.pt/2025/06/21/ciencia/opiniao/bolsas-promessas-reforma-falta-ciencia-portugal-2136865

https://expresso.pt/opiniao/2025-07-29-cativacoes-recorde-e-dividas-malparadas-como-a-fct-se-tornou-o-travao-invisivel-da-investigacao-8b2b576c

https://www.publico.pt/2025/08/21/ciencia/opiniao/paradoxo-extincao-fct-reforma-estado-menos-ciencia-2143832

and a more recent peace on AI, must be really usefull to write all the fake papers

https://expresso.pt/opiniao/2025-12-08-o-cientista-na-era-do-assistente-incansavel-quando-a-ia-forca-a-redesenhar-a-carreira-cientifica-ea20762d

LikeLiked by 3 people

Here some of Joao Conde’s coauthors.

Hossein Danafar:

https://pubpeer.com/search?q=%22+Hossein+Danafar%22+

Hamed Nosrati

https://pubpeer.com/search?q=%22Hamed+Nosrati%22+

And this women-hating fraudster Rohit Srivastava

https://pubpeer.com/search?q=%22Rohit+Srivastava%22+

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lisbon retraction

Lisbon retraction.Frontiers | Retraction: miR-335 targets LRRK2 and mitigates inflammation in Parkinson’s disease https://share.google/xa39m6FVDTo9T5jqt

LikeLike

Lisbon retraction.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-025-06663-5

LikeLike