In the Chinese paper mill universe, gender equality reached impressive heights. Women get prostate cancer, while men get breast cancer with same frequency as women, and uterus cancer on top. And why shouldn’t this happen, nobody reads those “research studies” anyway, they are published predominantly in certain pay-to-defecate Italian and Graeco-Serbian latrines unconvincingly parading as a peer-reviewed scholarly journals, which nevertheless remain PubMed-listed exactly because NOBODY cares.

Well, Smut Clyde cares, he is probably the only actual reader whom that European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences (ERMPS) or Journal of Balkan Union of Oncology (J BUON) ever had, at least the only one who bothered to read beyond the titles of these “clinical studies”, and who am I to try and stop him. Anyway, I just found out that the ERMPS publisher Verduci Editore also publish the Harvard professor David Sinclair, and he is a genius, according to all proper science journalists.

So yes, dear reader, this is another Chinese paper mill story, brought to you by Smut Clyde in collaboration with Elisabeth Bik and Tiger BB8. As customary for Chinese paper mills, it will be about fake science of non-coding RNA, which is a due punishment to western scientists for overhyping this research field beyond recognition. This time it’s not just some fake cell culture experiments or fake rodents, but hundreds of utterly fake cancer patients evolving fake cancers and dropping dead on command to prove some fake claims about some randomly picked miRNA or lncRNA or circRNA. The cheap paper mill products never bothered to fake their clinical data properly in those cases, hence the women with prostate cancer. It’s not like anyone minded, so far anyway. There will also be fictional babies and toddlers of stretchable age signing informed consent, and actual sea lions!

Here is Smut Clyde’s Google Sheets document, with 100 utterly made-up clinical studies traced to the same paper mill; and a pdf copy to download for the Chinese readers from behind the Great Chinese Firewall:

Haemophilia is, like enlargement of the prostate, an exclusively male disorder. But not in this work

By Smut Clyde

How did the Chinese epidemic of prostate cancer in women go unremarked for so long? Only now has Elisabeth Bik noticed a series of papers in which sex was not a risk factor for the condition. Notably, Pan, Song & Gao (2019) [16].

In two of these cases, the situation is complicated by similarities to other papers about bladder cancer, raising the possibility that the problem is one of systematic misdiagnosis. Wu et al (2018) [4] and Wang et al (2018) [5]…

Zhai et al (2019) [11] and Feng et al (2020) [24].

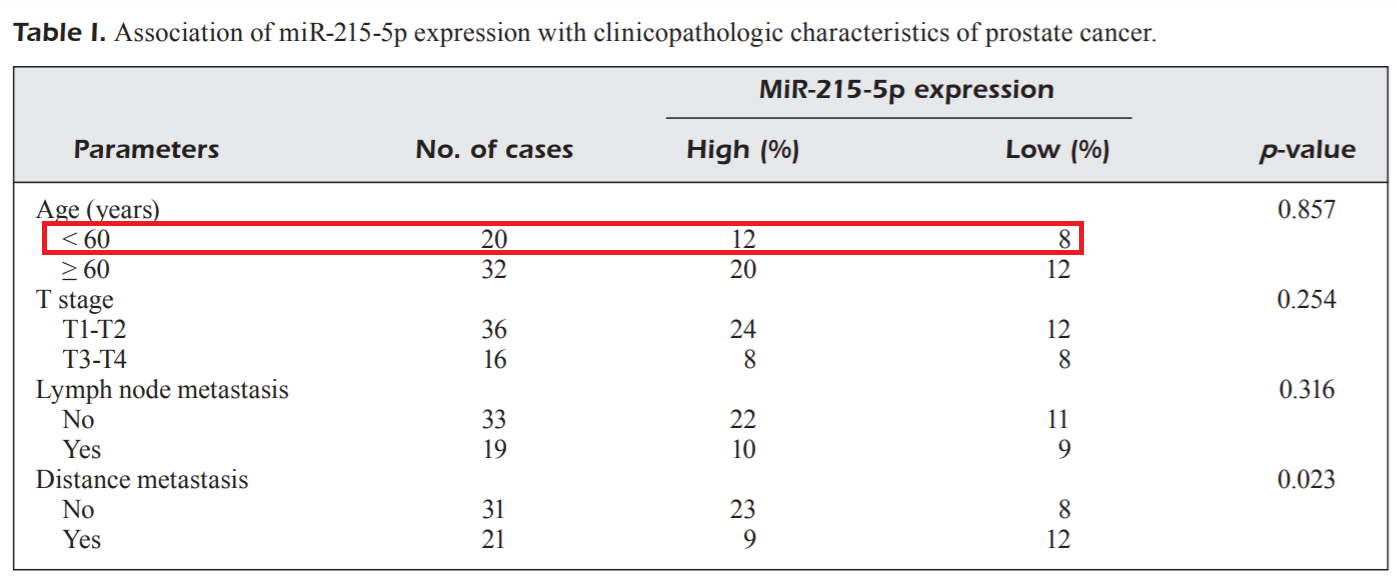

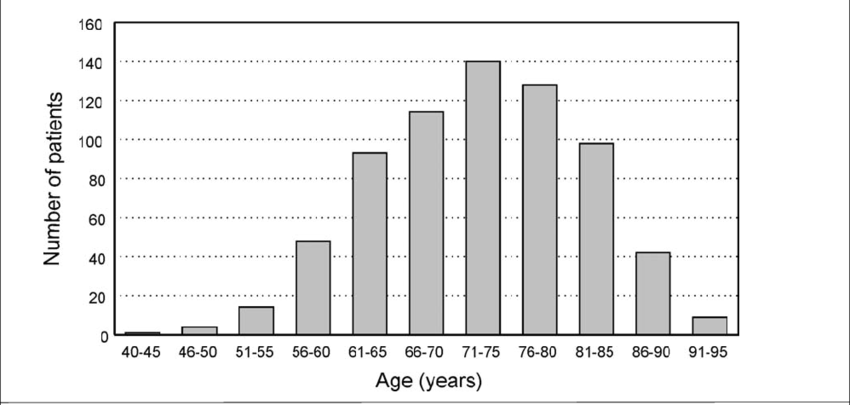

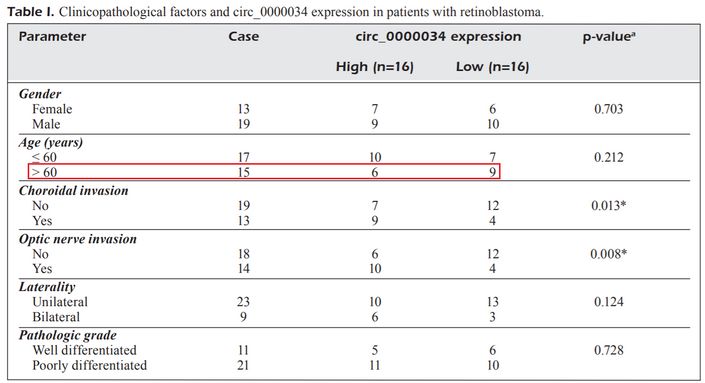

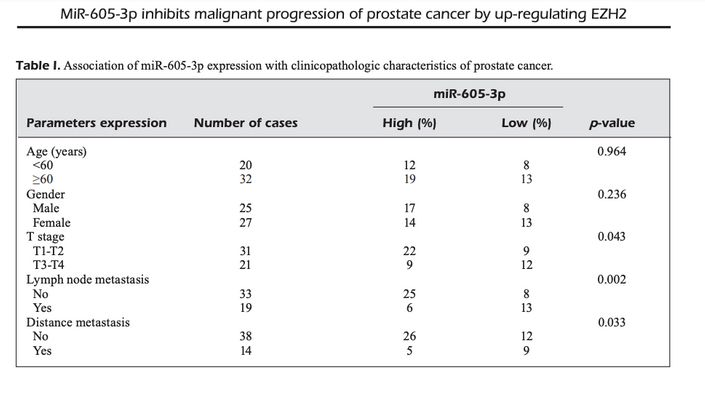

Maintaining our male-centric focus on the prostate, closer attention reveals that the median age at diagnosis was somewhere near 60, contra the usual finding in mainstream Western oncology that the age distribution for prostate cancer skews towards the elderly. As well as the examples above, here’s Table 1 from Chen et al (2020) [19]:

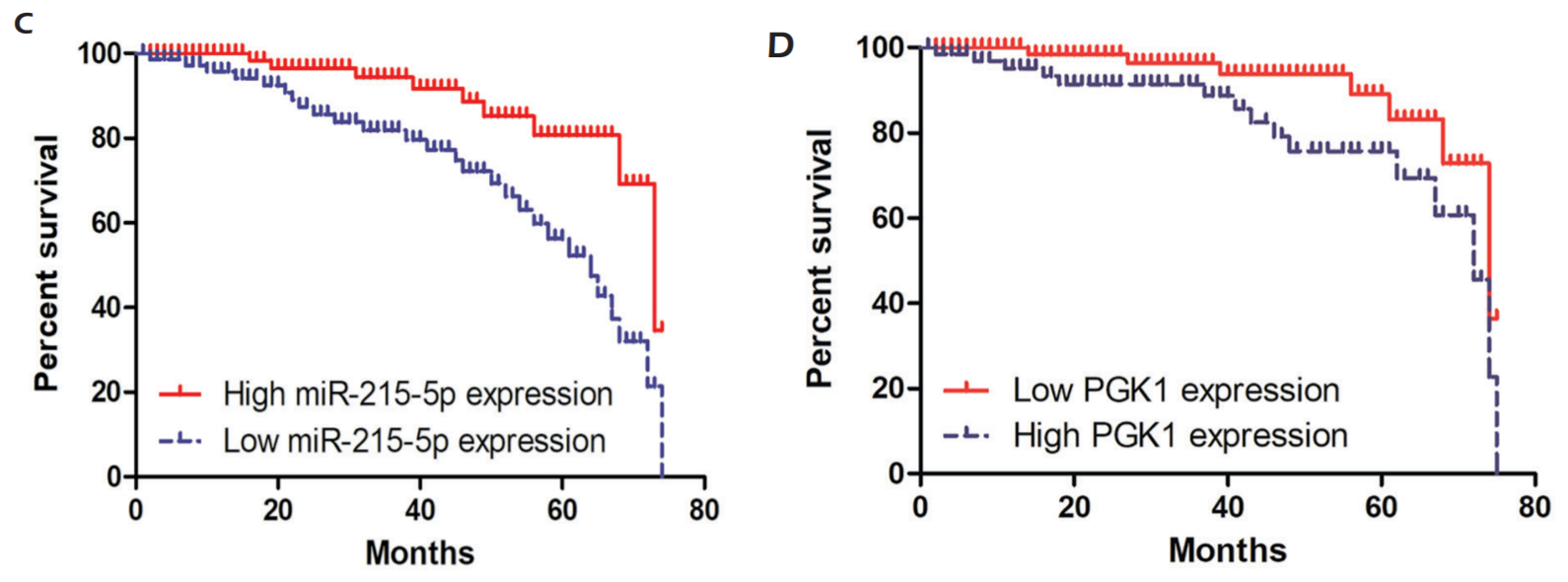

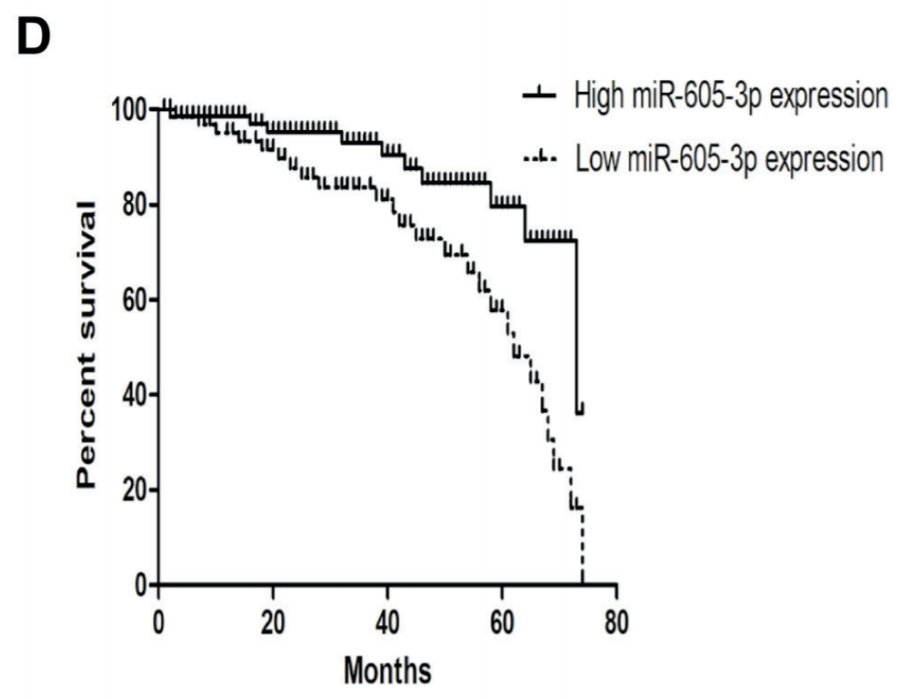

The survival rate was uniformly dreadful, with a precipitous nose-drive at 75 months post-diagnosis. The usual prognosis is more optimistic… PCa is often so indolent that observation is prefered to treatment. None of this redounds to the credit of Chinese oncologists.

[16] again, and Fan et al (2019) [15]:

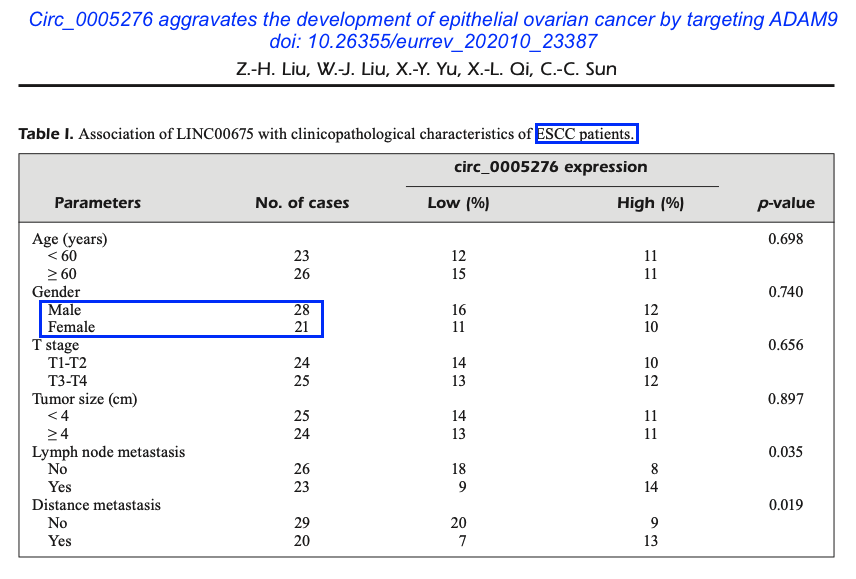

Their competence is further called into question by a paper in which equal numbers of men and women were diagnosed with a type of ovarian cancer (Liu et al (2020) [26]). Unless it was esophagal squamous cell carcinoma. Though who knows for sure in this crazy mixed-up world?

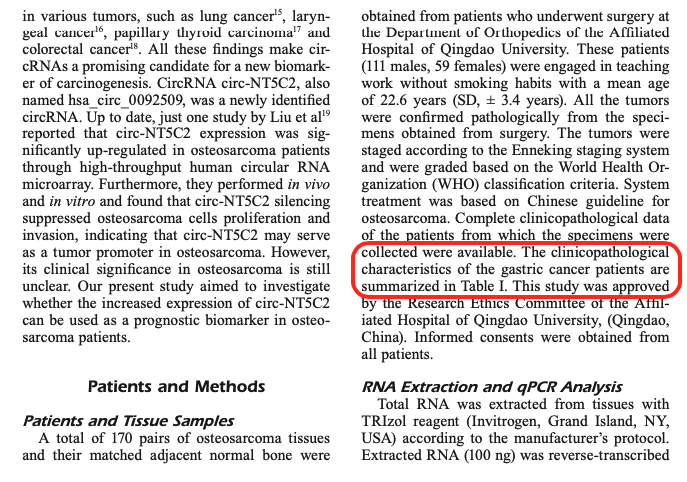

The possibility of misdiagnosis appears again in Nie et al (2018) [6] in which the cancer of interest manifested as osteosarcoma in the title, but switching in the text between brain, liver, stomach and cervix, migrating around the body faster than a wayward uterus. If nothing else, the indeterminacy provided other authors with more opportunities to cite the paper.

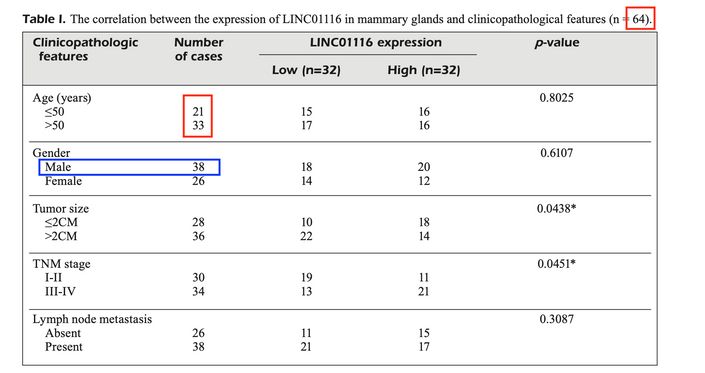

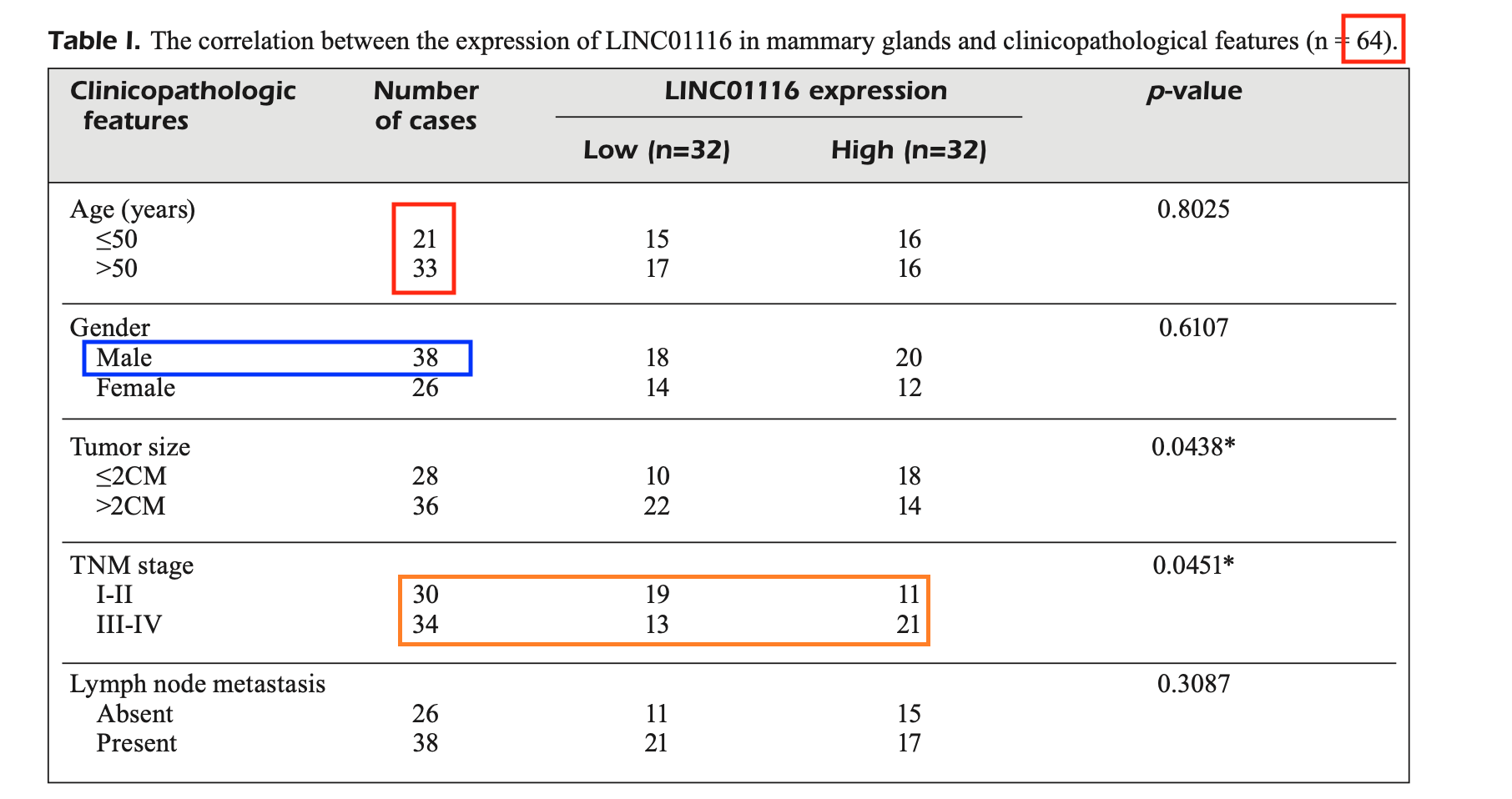

Meanwhile, in a series of (at least) 11 papers, other contributors to the same journal hinted at an epidemic (again in China) of male breast cancer. If nothing else, this will redress the balance. We might as well begin with Hu et al (2019) [2] and their 64 cases…

In this paper, LINC01116 expression was analyzed in 64 breast cancer tissues and 30 normal breast tissues.

However, there is nothing in the paper about when and where these samples were collected. Where did the normal breast tissues came from? From volunteers? Of even more concern, there is no data on IRB approval or patient consent.

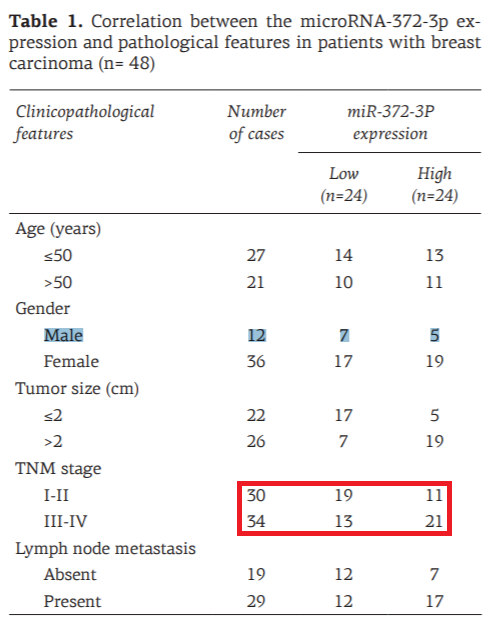

Table 1 appears to contain some data on the 64 patients, but the numbers do not always add up to 64 (Age row).

And according to Table 1, 38 of the breast cancer patients were male. Now, men can get breast cancer but that is rare, and one certainly would not expect that more than half of all breast cancer patients enrolled in a study would be male.

There appear to be lots of other data missing. E.g. how was the data obtained shown in Figure 1A? There is nothing shared about e.g. RNAseq or microarray data analysis, and it seems that many more than 64 patient data were analyzed here.

Awkwardly, some but not all of the values from [2]’s Table 1 reappeared in Fan et al (2018) [8], with 48 cases, give or take. Whoever really churned out these manuscripts was working at speed, undistracted by concern for internal consistency.

Others in the list are Luo et al (2018) [7] and Liu et al (2019) [10], with almost the same 72 cases each…

…though the demographics of the patients are not all that link [7] and [10].

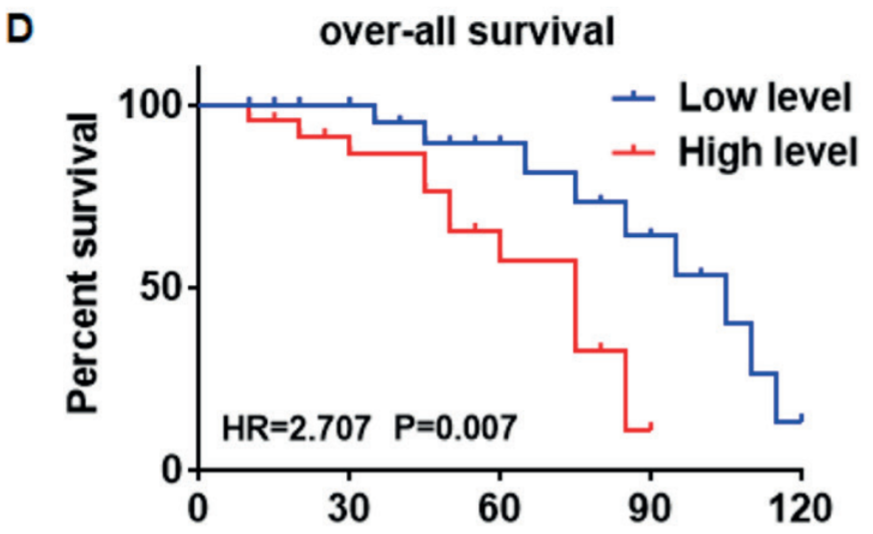

Mustn’t forget Hu et al (2019) [12], with n=48; Zeng, Yang & Wu (2019) [13], with n=66; Niu, Zhang & Ma (2019) [14], with n=52; Wang et al (2019) [17], with n=44; Li et al (2019) [18], with n=65; Zheng, Li & Li (2020) [20], with n=40; and Zhang, Liu & Wang (2020) [23] with n=48. Together these accumulate to a large sample size but I cannot recommend a meta-analysis of the papers. Are there more Kaplan-Meier survival plots that resemble combs (in the minds of some observers) or walls built of Lego blocks (according to others), nose-diving at 75 months? Are there correlation scatterplots sharing more data-points than one might expect? These are rhetorical questions.

Perhaps all this is related somehow to the time travel technology available to Chinese medical researchers. This has received little attention in the media, but it must exist, for how else could oncologists recruit patients “from April 2016 to December 2018“, and follow them across a decade to the date range April 2026 to December 2028, in order to publish the results in 2020 including plots of their 10-year survival trends? (Chen et al, 2020) [22]

The vehicle for most of this malarkey is ERMPS, the European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Science. It should already be familiar to readers, as the conduit of choice for multiple papermills reported here and by Dr Bik at her Science Integrity Digest. Word has gone out across the fake-paper industry that it’s hospitable toward their products, with relaxed or negotiable standards of peer review (I imagine the papermill studios scratching the Interweb equivalent of hobo signs to signal one another). It is a write-only journal — a category also occupied by J.BUOn, Oncology Research, J BrouHaHa, and every e-Century spigot — and unsuitable for scientists who actually want their result to be read. Motivated by profit as well as altruism, the business model is to help Chinese clinicians meet their requirement of ‘publications in an international journal’. But is ERMPS worth dunking on a 7′ hoop blogging about?

Mirabile dictu, these papers do turn up in literature searches (because PubMed listings), and they are indeed cited in systematic reviews and syntheses, elevating them from the peripheral, parasitical domain of fantasy research into the real-world literature of experiment-based science. Then they are copy-pasted from one lazy author’s References section to another, amassing double-digit or even triple-digit citation credibility. A shout-out here to Jin et al (2017) [1], cited 106 times, says the imperfect count of G**gle Scholar. Despite the glories of Figure 2D/E.

So pointing and laughing at these low-effort algorithmic permutations (and on the nimrods who cite them) is not just a guilty pleasure; it’s also the right thing to do. This lets me feel less guilty about tabulating them all in a Google spreadsheet.

So far it contains ~200 entries, mostly from ERMPS, but not exclusively. JBUOn contributed 11 papers. Two each from Medical Science Monitor and Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. A couple of Spandidos journals. The spreadsheet subsumes the five papers from Dr Bik’s “Mini papermill“. There will be other infestations in journals where we haven’t looked yet, so the surface is so far barely scratched.

This is still enough to draw a few broad generalisations. The ERMPS papermill is at the bargain-basement end of the spectrum of quality. The papermiller is careful to vary the phrasing from one iteration to the next, but he or she does not put much effort into customising or individualising the numbers. The similarly-themed {non-coding-RNA}-{cell-signalling-pathway}-{cancer} compositions that fill the space in other, higher-end journals come from papermills that spend a little more time to randomise each scatterplot and distribution from scratch, and to ensure that the demographics of each imaginary patient match the title… I surmise that they charge a little more.

“Retinoblastoma (RB), a normal intraocular tumor occurring in the retina, is diagnosed in infants and children”.

A good beginning, though “normal” is an odd choice of words.

“Written informed consent was provided by all participants.”

Infants and children were providing written informed consent?

Half the infants and children in this study were older than 60.

Most authors resisted the emailed invitations to join the PubPeer discussions of their work, to no-one’s surprise, as the contact addresses are generally single-use burner accounts at 163.com or aliyun.com or qq.com or sina.com. With exceptions [19].

After checking and considering, I informed the magazine to withdraw the manuscript by e-mail that day. We will do the experiment again according to the design of the subject, and statistical analysis of the data. I apologize for my lack of rigorous scientific attitude and misleading readers. At the same time, thank you very much for your work and reminder.

Mind you, what appear to be cromulent institutional e-addresses do appear in the spreadsheet. In particular, Guanlin Wu, corresponding author of [24], uses the same e-address — affiliated to the Charité university hospital in central Berlin — on what look like legitimate papers. Again, Weihua Tong, corresponding author for Tong et al (2020) [25]. Hailiang Hu – Associate Professor of Pathology at Duke University Medical Center — is listed as a non-corresponding author for [19] but has been invited to the conversation anyway. In these cases, the authors’ lack of response to the PubPeer blandishments is harder to understand. It is also regrettable, as they could have first-hand accounts of what it’s like to contact and negotiate with the papermill.

I’m not sure what’s going on with e-addresses like sandra.gruber@students.clatsopcc.edu or brandon.martin5@pcc.edu. Are the corresponding authors of Fang et al (2020) [27] and Qiao et al (2021) [28] really students at Community Colleges in Oregon? Is there a trade in email accounts based there? Are they just taking the piss?

The basic template includes a declaration that approval for the fictitious research was granted by an Ethics Review committee at the author’s hospital. Then, when a group of authors from different hospitals scrape together the cash to have their names affixed to the published version, our papermiller feels no urgency about amending the manuscript to specify which hospital provided the patients or housed the Ethics Committee. Sometimes he or she forgets the ethics declaration completely, leaving no indication that the supposed patients willingly donated their tissues and spare body parts to the researchers. The ERMPS editors do not demur or raise ethics concerns: they know perfectly well that the ‘patients’ only exist as entries in a spreadsheet of randomised numbers.

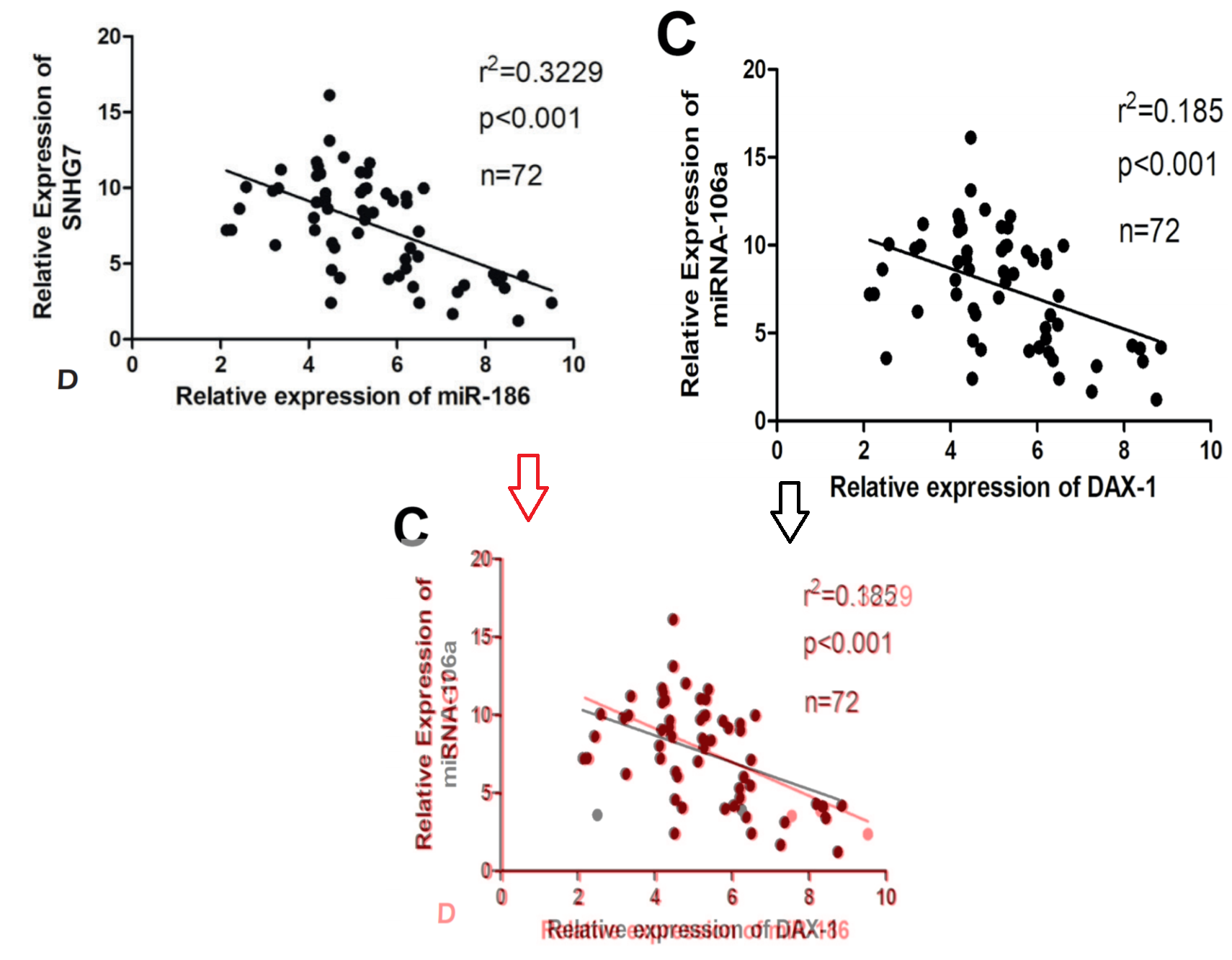

Another of the recurring elements in the constellation that characterise this papermill are scatterplots of biomarker expression levels, purportedly showing a correlation between non-coding-RNA X and signalling molecule Y. The papermiller does not waste time customising these either: why bother populating an entire random-value table for each opuscule?

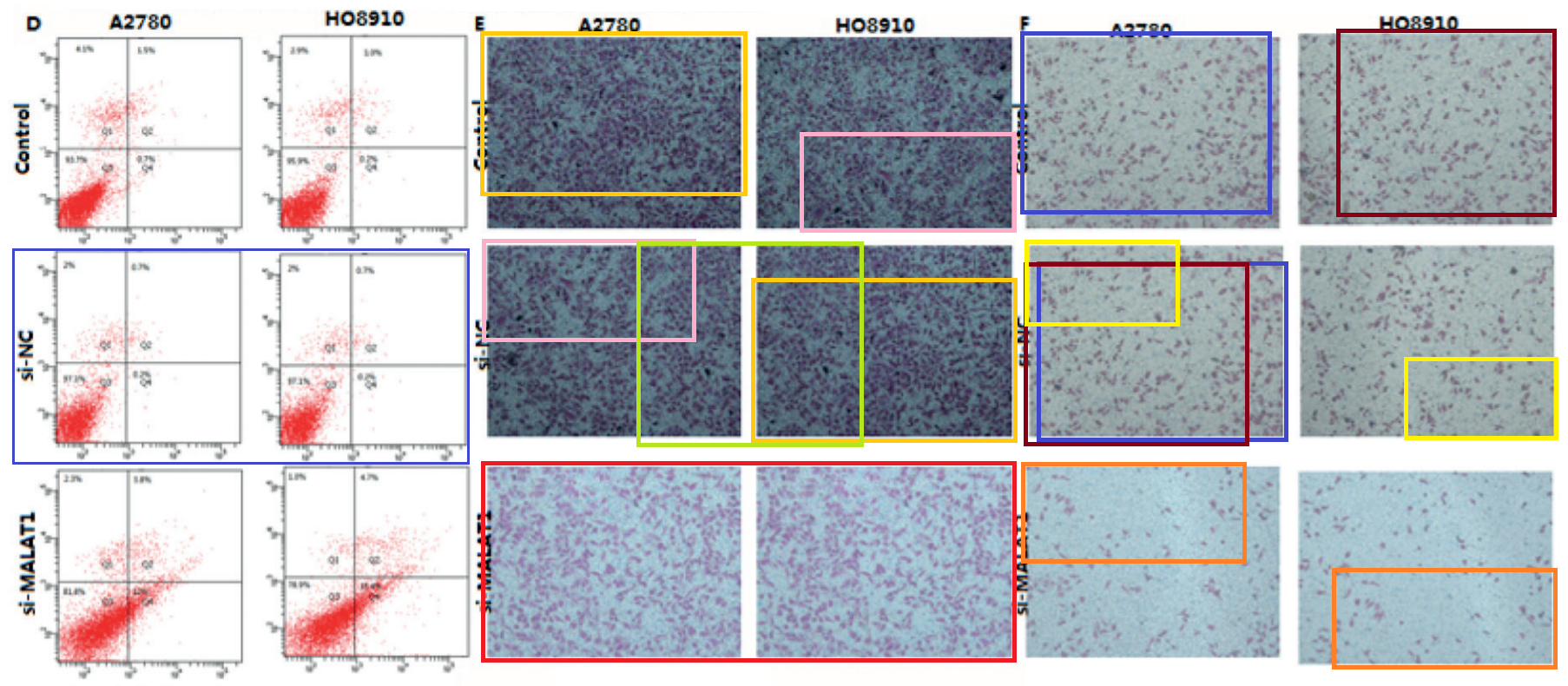

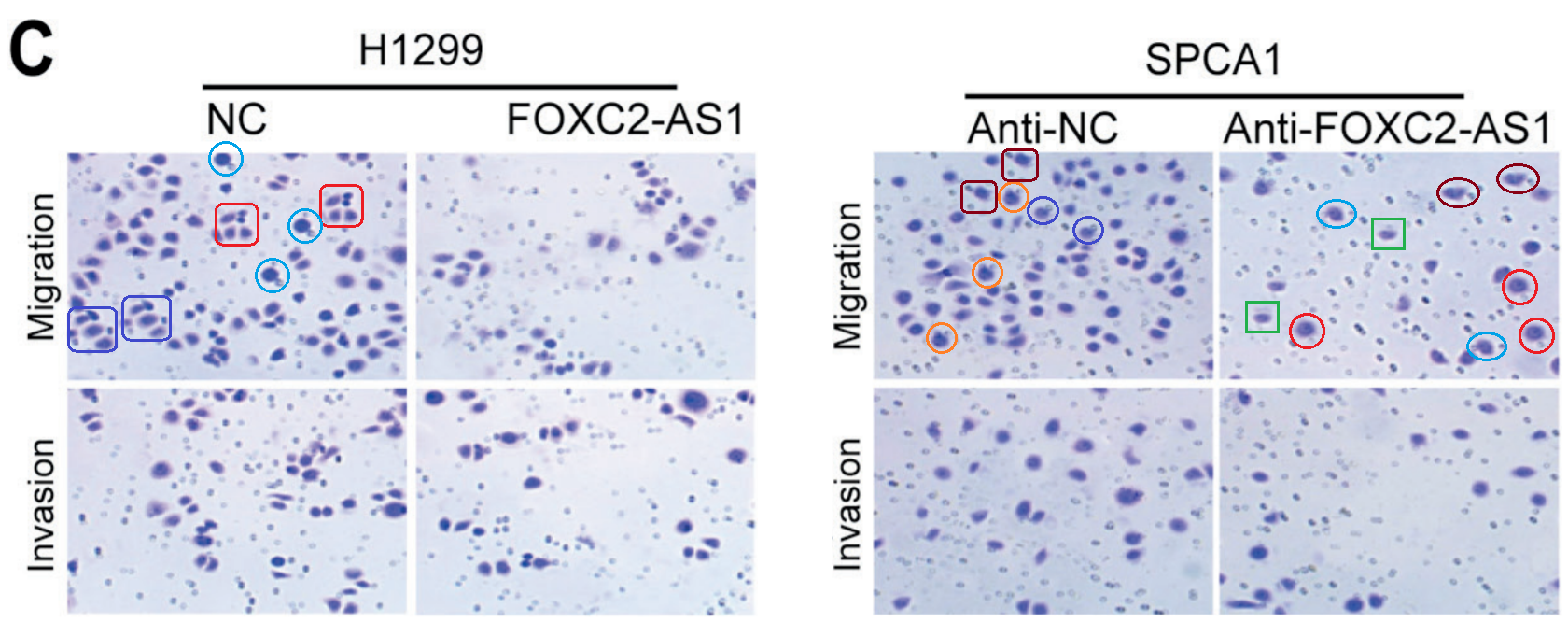

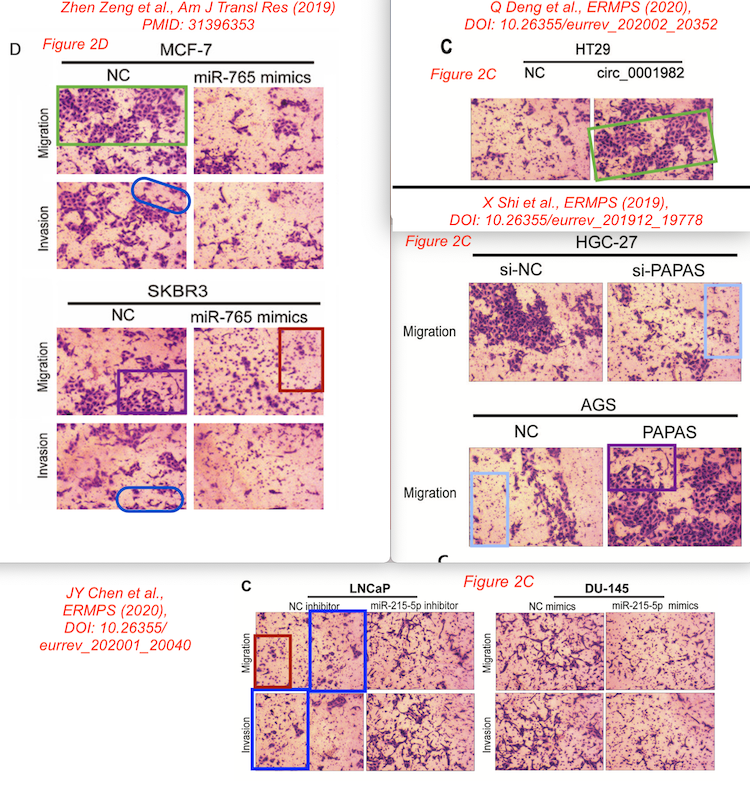

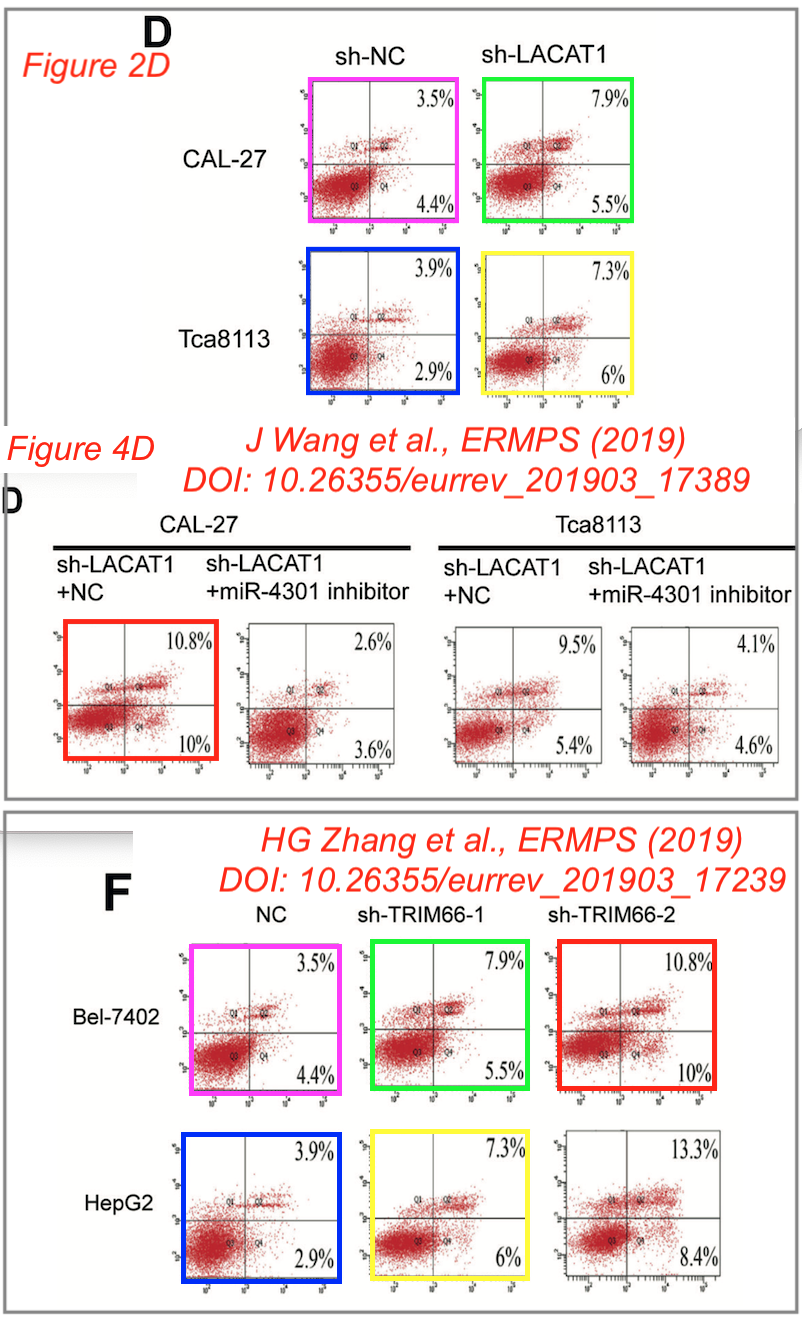

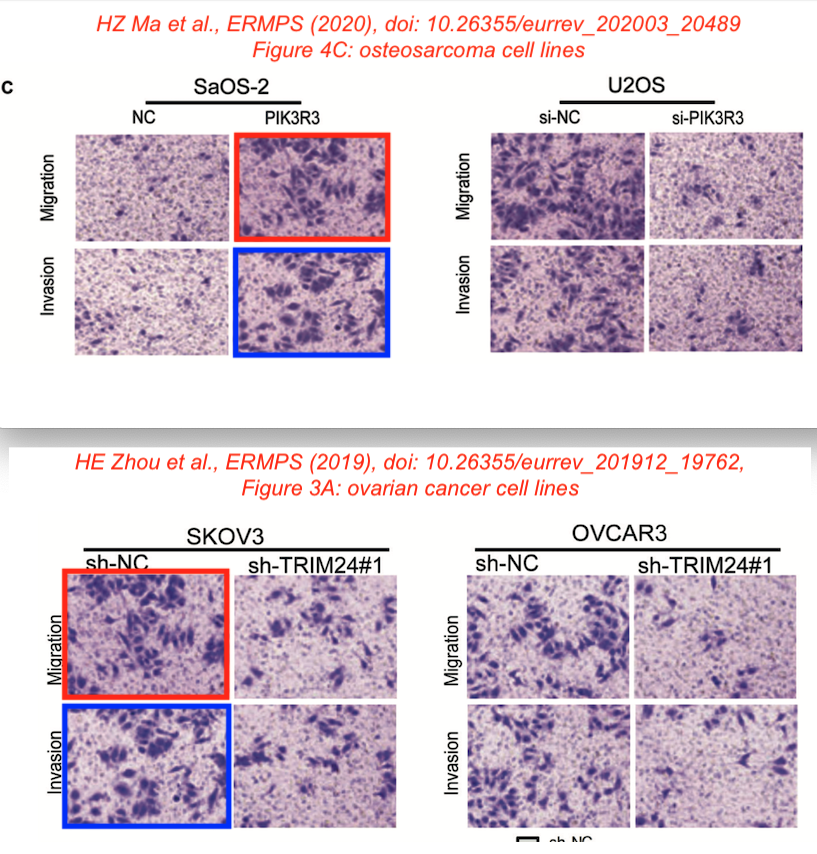

Western Blots, transwell-assay invasion microphotographs, scratch-healing-assay migration microphotographs, flow cytometry scatterplots… these are optional extras, festooned like Christmas lights around the rigid armature of the paper-generating algorithm. I suspect that the papermiller simply steals them from the archives of other write-only journals. It is a sad reflection on those journals and their contributors that any images copy-pasted from them could easily be a photoshop creation. Wu et al (2019) [9]:

Sometimes the purloined images overlap or are re-used across papers.

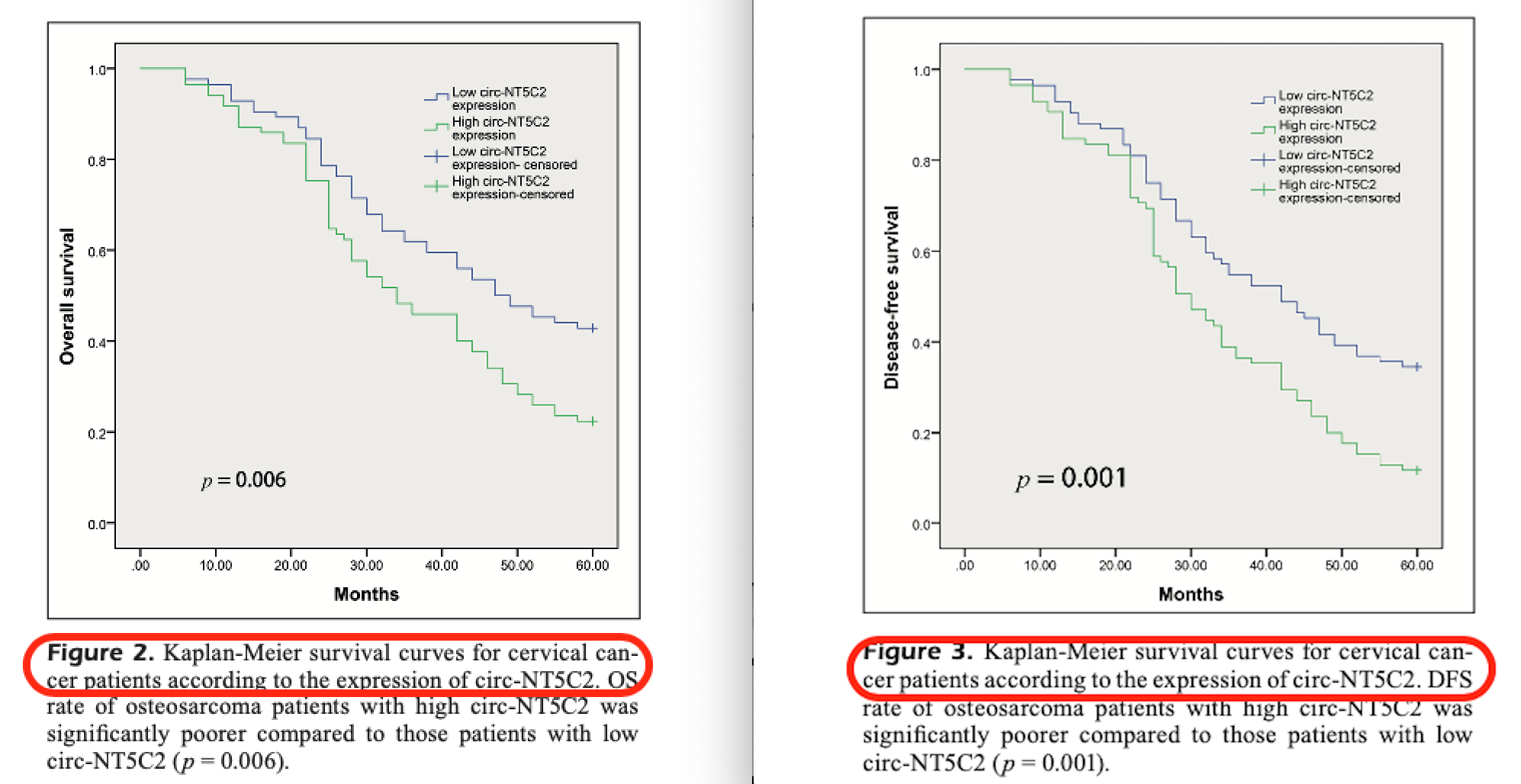

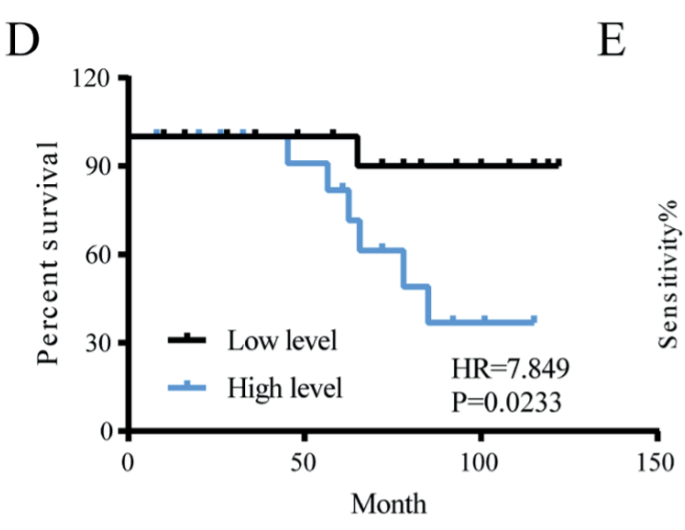

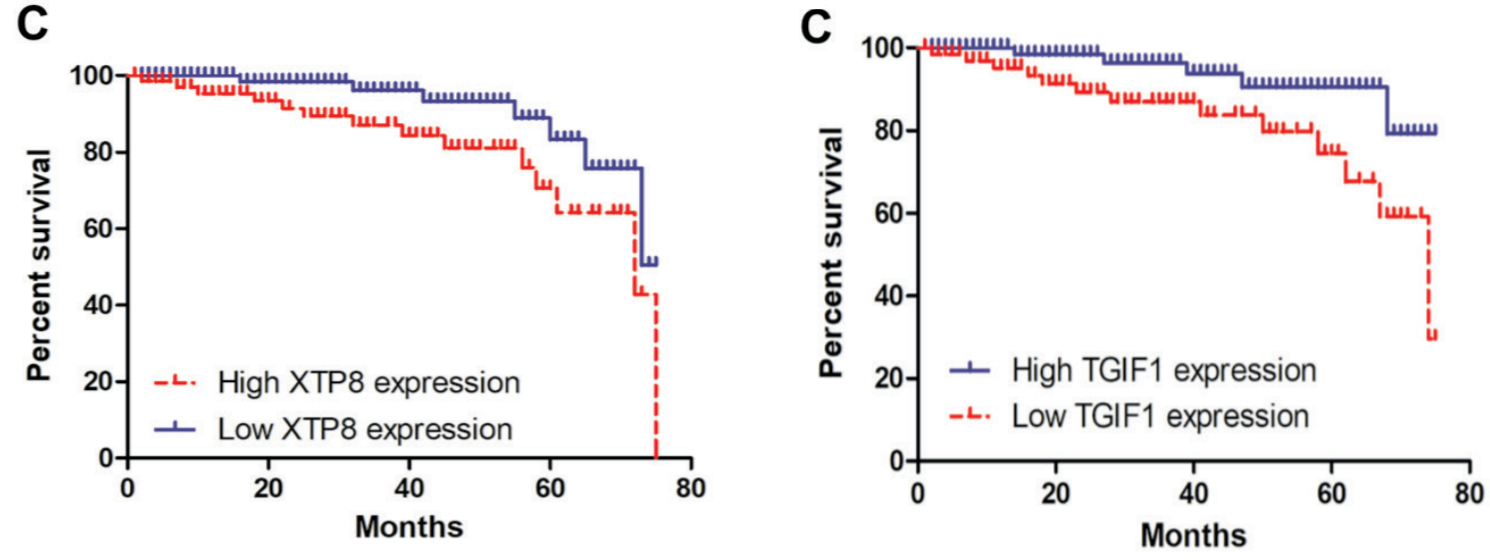

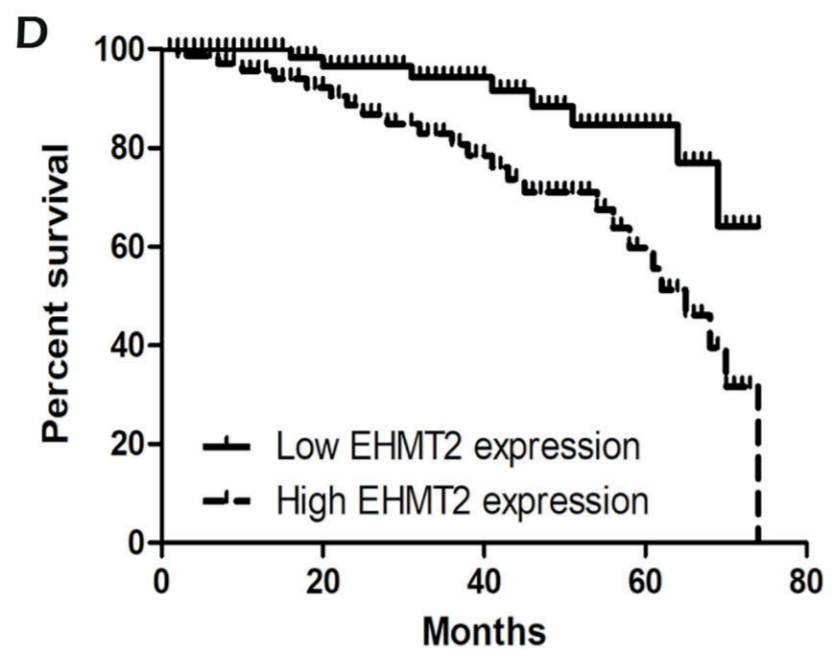

If I learned one thing from delving into this oeuvre, it is that any set of post-treatment survival-time data for any cancer can be dichotomised into half-groups with higher or lower values of any given biomarker, and one half or both will all be dead after 75 months. The drop-off in the final months is alarming, and I worry that a policy of euthanasia is widespread in provincial Chinese hospitals.

More curious still, many of these papers dichotomise their data twice with different biomarkers as the criteria, to show their different implications for that cancer’s recalcitance to treatment, and the pairs of survival times are never compatible. If you find yourself diagnosed with gastric cancer, insist that your sample of patients is grouped according to levels of TGIF1 expression rather than by XTP8, as the overall prognosis is much better that way: Jia et al (2020) [21]

In standard Kaplan-Meier plots, the occasional vertical ticks along the curves show dates when subjects fell off the researchers’ radar and their subsequent health status became unknown, “right-censored”. In the ERMPS versions the ticks are as regular and close-spaced as those of Sticklebricks. The papermiller seems to be unaware of their original purpose but knows that ticks are part of a proper K-M plot, so they are used as ornamental crenellation, or to discourage pigeons from nesting.

In standard Kaplan-Meier plots, the occasional vertical ticks along the curves show dates when subjects fell off the researchers’ radar and their subsequent health status became unknown, “right-censored”. In the ERMPS versions the ticks are as regular and close-spaced as those of Sticklebricks. The papermiller seems to be unaware of their original purpose but knows that ticks are part of a proper K-M plot, so they are used as ornamental crenellation, or to discourage pigeons from nesting.

Much as “(%)” appears in the column headings of almost every Table 1 as a decorative dado, not because the numbers of fabulated patients in each subgroup are expressed anywhere as percentages ([4], [5], [6], [7], [10], [11], [16], [24], [26], …).

I also learned that in China at least, smoking is not a risk factor for lung cancer after all, with non-small-cell lung cancer developing in smokers and non-smokers alike: Dong, Meng & Li (2018) [3]. This is less sensational than the counter-intuitive discoveries about breast cancer and prostate cancer, or the time-travelling in the same paper, but I still feel that it deserves wider dissemination.

Bonus Breast-cancer paper: Bi et al (2018). One of these citations is not like the others. EndNote was having a bad day.

References

- ‘LncRNA MALAT1 promotes proliferation and metastasis in epithelial ovarian cancer via the PI3K-AKT pathway‘. Y Jin, S-J Feng, S Qiu, N Shao, J-H Zheng (2017). [PubPeer].

- ‘LncRNA LINC01116 competes with miR-145 for the regulation of ESR1 expression in breast cancer‘. H-B Hu, Q Chen, S-Q Ding [PubPeer].

- ‘Long non-coding RNA SNHG15 indicates poor prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer and promotes cell proliferation and invasion‘. Y-Z Dong, X-M Meng, G-S Li (2018). [PubPeer].

- ‘Long non-coding RNA LINP1 promotes the malignant progression of prostate cancer by regulating p53‘. H.-F. Wu, L.-G. Ren, J.-Q. Xiao, Y. Zhang, X.-W. Mao, L.-F. Zhou (2018). [PubPeer].

- ‘UPK1B promotes the invasion and metastasis of bladder cancer via regulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway‘. F.-H. Wang, X.-J. Ma, D. Xu, J. Luo (2018). [PubPeer].

- ‘Circular RNA circ-NT5C2 acts as a potential novel biomarker for prognosis of osteosarcoma‘. W-B Nie, L-M Zhao, R Guo, M-X Wang , F-G Ye (2018). [PubPeer].

- ‘LncRNA SNHG7 promotes development of breast cancer by regulating microRNA-186‘. X. Luo , Y. Song, L. Tang, D.-H. Sun, D.-G. Ji [PubPeer].

- ‘MicroRNA-372-3p promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast carcinoma by activating the Wnt pathway‘. Xiaodong Fan, Xuandong Huang, Zhi Li, Xinyan Ma (2018). J BUOn [PubPeer].

- ‘Mechanism of LncRNA FOXC2-AC1 promoting lung cancer metastasis by regulating miR-107‘. X-F Wu, J-T Lu, W Chen, N Wang, J-C Meng, Y-H Zhou (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘MiRNA-106a promotes breast cancer progression by regulating DAX-1‘. C. Liu, Y.-H. Song, Y. Mao, H.-B. Wang, G. Nie (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘Mechanism of LncRNA ROR promoting prostate cancer by regulating Akt‘. X-Q Zhai, F-M Meng, S-F Hu, P Sun, W Xu (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘LncRNA RUSC1-AS1 promotes the proliferation of breast cancer cells by epigenetic silence of KLF2 and CDKN1A‘. C-C Hu, Y-W Liang, J-L Hu, L-F Liu, J-W Liang, R Wang (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘MicroRNA-765 alleviates the malignant progression of breast cancer via interacting with EZH1‘. Zhen Zeng, Yichen Yang, Hengyu Wu (2019). Am J Transl Res [PubPeer].

- ‘MiRNA-221-5p promotes breast cancer progression by regulating E-cadherin expression‘. X.-Y. Niu, Z.-Q. Zhang, P.-L. Ma (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘EHMT2 promotes the development of prostate cancer by inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway‘. H.-T. Fan, Y.-Y. Shi, Y. Lin, X.-P. Yang (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘MiR-605-3p inhibits malignant progression of prostate cancer by up-regulating EZH2‘. M.-Z. Pan, Y.-L. Song, F. Gao (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘DCLK1 promotes malignant progression of breast cancer by regulating Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway‘. Y-L Wang, Y Li, Y-G Ma, W-Y Wu (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘FOXK1 promotes malignant progression of breast cancer by activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway‘. Z.-Q. Li, M. Qu, H.-X. Wan, H. Wang, Q. Deng, Y. Zhang (2019). [PubPeer].

- ‘MiRNA-215-5p alleviates the metastasis of prostate cancer by targeting PGK1‘. J-Y Chen, L-F Xu, H-L Hu, Y-Q Wen, D Chen, W-H Liu (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘LncRNA AK024094 aggravates the progression of breast cancer through regulating miRNA-181a‘. T-Z Zheng, Y-T Li, W-J Li (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘XTP8 stimulates migration and invasion of gastric carcinoma through interacting with TGIF1. K. Jia, Q.-H. Wen, X. Zhao, J.-M. Cheng, L. Cheng, M. Xi (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘IL-6 stimulates lncRNA ZEB2-AS1 to aggravate the progression of non-small cell lung cancer through activating STAT1‘. T. Chen, J. Li, M.-H. Zhou, L.-J. Xu, T.-C. Pan (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘SAPCD2 promotes invasiveness and migration ability of breast cancer cells via YAP/TAZ‘. Y. Zhang, J.-L. Liu, J. Wang (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘Circ_0061140 promotes metastasis of bladder cancer through adsorbing microRNA-1236‘. F Feng, A-P Chen, X-L Wang, G-L Wu (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘LINC00346 accelerates the malignant progression of colorectal cancer via competitively binding to miRNA-101-5p/MMP9‘. W-H Tong, J-F Mu, S-P Zhang (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘Circ_0005276 aggravates the development of epithelial ovarian cancer by targeting ADAM9‘. Z.-H. Liu, W.-J. Liu, X.-Y. Yu, X.-L. Qi, C.-C. Sun (2020) [PubPeer],

- ‘MicroRNA-198 inhibits metastasis of thyroid cancer by targeting H3F3A‘. J Fang, J-M Zhu, H-L Dai, L-M He, L Kong (2020). [PubPeer].

- ‘LINC00483 is regulated by IGF2BP1 and participates in the progression of breast cancer‘. Y.-S. Qiao, J.-H. Zhou, B.-H. Jin, Y.-Q. Wu, B. Zhao (2021). [PubPeer].

- ‘Circular RNA circ_0000034 upregulates STX17 level to promote human retinoblastoma development via inhibiting miR-361-3p‘. H. Liu , H.-F. Yuan, D. Xu, K.-J. Chen, N. Tan, Q.-J. Zheng (2020). [PubPeer].

Looks to me the miRNA and lncRNA field is pretty much dead as an active field of inquiry in the west because its been tainted by this crap from China. As the technology for faking data only improves, more fields will succumb. I think science is not quite dead yet, but will be say 30 years from now, as there will be nothing published that you can really trust, because the good stuff will be mixed in from the crap and you will not be able to tell the difference. Then governments will smartly remove funding, and we will go back to a system of independently wealthy people doing science. Think Bill Gates and his backyard lab, pulling schenaigans of the sort like William Wollaston (the somewhat dubious discoverer of palladium).

LikeLike

These hacks cannot kill science, as long as its practitioners have functioning bullshit detectors. It is quite easy to integrate an origin screen into such a device, as I have done with mine. The tricky part is determining why good journals publish bad science – if we could fix that we could leave our friends here to their own happy corner of the scientific hog wallow.

LikeLike

Pingback: Pari opportunità (oncologiche) - Ocasapiens - Blog - Repubblica.it

Pingback: A MAGIcal Special ERMPS Issue – Science Integrity Digest