By announcing a radical and controversial Plan S, the European Union has created facts on the ground with Open Access (OA), which is to become Gold standard (pun intended) by the year 2020. I am honoured to present you, exclusively on my site, an Appeal by several European scientists protesting against Plan S, which they fear will deprive them of quality journal venues and of international collaborative opportunities, while disadvantaging scientists whose research budgets preclude paying and playing in this OA league. The appeal authors around the Sweden-based scientist Lynn Kamerlin offer instead their own suggestions how to implement Open Science.

On 11 July 2018, Robert-Jan Smits, the Open Access Envoy of the European Commission was holding a panel discussion at a major science conference in Toulouse, France. Another notable participant was Kamila Markram, CEO of the Switzerland-based Open Access (OA) publisher Frontiers, who also advertised for her business there. Founded by Kamila and Henry Markram in 2007 on the premise to give every, even the most outlandish, paper a fair chance to get published (starting with their own autism research), the publisher is now largely owned by the German giant Holtzbrinck. Frontiers presently advises EU Commission on the future of scholarly publishing as member of a relevant Horizon 2020 expert group and the EU-funded otherwise academic project OpenUP.

At that Toulouse meeting, while sitting next to Frontiers CEO, Smits announced a mysterious “Plan S”, which would “decisively advance towards the Open Access of scholarly publishing by 2020”. On 4 September 2018, the full Plan S was revealed by the Science Europe funder lobby group representative Marc Schilz, published exclusively in a perspective article in Frontiers (but also in the non-profit PLOS). Behind the plan stands a cOAlition S, a network of European research funders, who now decreed that

“By 2020 scientific publications that result from research funded by public grants provided by participating national and European research councils and funding bodies, must be published in compliant Open Access Journals or on compliant Open Access Platforms.”

Plan S is supported next to EU Commission and ERC by several key national research funding agencies. Even those who haven’t signed yet, like the German DFG, are generally positive towards Plan S, though concerned about the costs (Germany is currently in a stand-off with Elsevier about an OA agreement, having cancelled all subscriptions).

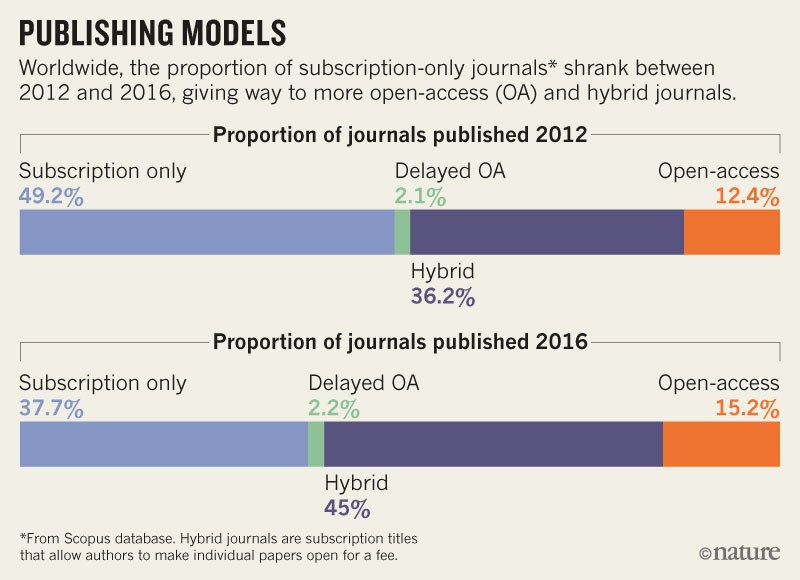

This is what Plan S is about: the orientation of academic evaluations on the journal impact factor is to become a thing of the past; the OA article processing charges (APC) are to be capped, and paid by funders and universities instead of scientists from their research budgets. A peculiar aspect of Plan S is that researchers funded by cOAlition S signatories will be, from 2021 on, forbidden to publish in subscription journals, including in hybrid ones, where OA option is available at an extra cost. Sanctions for non-compliance, like funding withdrawal, are being discussed (though personally, I suggest to enforce retractions of illegally published papers as a much more entertaining approach. #Sarcasm). Post-publication archiving does not qualify as OA publishing, unless it happens immediately which contradicts all subscription publisher embargoes. This condition basically excludes 85% of journals for European scientists, including those most established and respected ones published by academic societies. Some society publishers, like EMBO, demand that APC are not capped too low, to allow their journals to continue selecting for quality and not quantity. US National Society journal PNAS now announced to retire its print edition and become online-only, which might also be a preparation to a flip to Gold OA.

Gold OA publisher Frontiers of course is ecstatic. Yet not all academics are happy with this destination for their research: they imagined Open Science movement to be something different.

Those interested can read my Frontiers reporting here, and my two cents on Open Science here, here and here. But now, the Open Letter by Kamerlin et al (all authors listed at the end).

A Response to Plan-S from Academic Researchers: Unethical, Too Risky!

Summary

Open access (OA) publishing in general has many advantages over traditional subscription, or toll access (TA), publishing: it not only makes science accessible to a larger public, but also expands the reach of individual researchers and the potential impact of their research. Plan S is a noble effort to move OA forward. However, Plan S targets one audience – TA publishers – without fully considering another – researchers themselves. Providing OA to publications is already possible and becoming common practice among researchers. Existing high-quality hybrid (OA + TA) professional (society) journals provide ample opportunities for OA publishing, while providing excellent quality-control systems based on best practice and long-term experience. Institutional repositories (sponsored by universities or professional societies) support Green OA, which provides researchers the opportunity to make even their exclusively TA publications OA. Yet, in the eyes of certain policy makers and funding bodies, the current system is apparently ‘wrong’ for several unclear reasons. Politicians, research councils, and funding bodies in 11 European countries (cOAlition S) have embraced a policy that favors a particular version of Gold OA and recently decided to accelerate the OA transition by signing on to Plan S. Within 2-3 years, researchers supported by the research councils and funding bodies signing on to Plan S will be required to publish in either in purely Gold OA journals – hybrid OA journal publication will be prohibited – or vaguely defined “compliant” OA platforms. Is this really a good idea?

Forbidding researchers to publish in existing subscription journals has many unwanted side effects, putting knowledge production & society at severe risk. Forced gold OA publishing could lead to higher costs of many high quality journals and an overload of papers of low quality or limited novelty in lower quality journals. Furthermore, in the likely event that the rest of the world will not join in, Plan S will severely hamper internationalization of PhD students and postdocs, and discourage collaborations between the cOAlition S countries and the rest of the world. Finally, insofar as it mandates a limited set of publication venues, Plan S violates researchers’ academic freedom.

So is Plan S objectively an advancement? We think not. Please read our standpoint detailed below, and see if you come to the same conclusion. We also provide alternatives that are less radical, and likely less costly, than Plan S.

The problems with Plan S

On the 4th of September 2018, a coalition of European and national research funders announced “Plan S” and “cOAlition S”, a combined bold step towards making all European research Open Access (OA) by 2020 [1]. Under the framework of this plan, researchers funded by these research councils and funding bodies would be obliged to make all their research immediately OA in pure Gold OA journals or “compliant” OA platforms, with hybrid (subscription based, or Toll Access – TA – plus Gold OA) publication only allowed as part of a transition period. The goals of this plan are ambitious and noble: it is impossible to argue with the premise that publicly funded research should be freely accessible to the public.

Clearly, greater openness, access, and transparency will greatly benefit both knowledge production and society as a whole.

However, while this plan has been welcomed by many, it has also been met with concern. Some of this concern has (unsurprisingly) come from publishers [2]. For instance, Springer Nature argues that this policy “potentially undermines the whole research publishing system” [3], and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the publisher of Science, argues that “implementing such a plan, in our view, would disrupt scholarly communications, be a disservice to researchers and impinge academic freedom” [4]. Both researchers and funding agencies have raised other concerns [5].

As academic researchers, with most of us based in Europe, we are extremely worried that Plan S will put the science, culture and economies of the cOAlition S countries at severe risk. In fact, Plan S may very well create a complete dichotomy of the global scientific society, separating 11 European countries and the EU from the rest of the world. Below, we provide a detailed account of the associated problems and issues we find associated with Plan S.

The problem of affordability

Our first concern is the fact that Plan S pushes researchers toward pure Gold OA as the desired model for publishing. This is problematic on several levels. While there are severe problems with the TA, subscription, model of publishing, all researchers have (in principle) the freedom to disseminate their research in any venue they choose, and it is the quality of their research, and not the size of their wallet, that determines whether they can publish in a given venue. While the TA model creates some inequality of access for readers (the so-called ‘paywall’), it creates a baseline equality of opportunity for researchers: if they have performed sufficiently good research, they will have the possibility to disseminate it in venues with high esteem and high visibility within the community of researchers. This concern is particularly critical for early career researchers, for retired researchers, for citizen scientists, for researchers from Inclusiveness Target Countries, and, in fact, for any researcher who for any reason is on a limited research budget, since forced-but-unfunded pure Gold OA effectively prevents them from disseminating their research in many reputable venues.

While subscription TA journals work with a reading paywall, pure Gold OA journals create a paywall for the researchers. We are aware that the current Plan S suggests putting a cap on article processing costs (APCs). However, it is unclear what this cap would be and whether policy makers will succeed in reducing APCs at all.

As researchers, we have witnessed APCs constantly increasing. Even ignoring the ever-growing number of predatory journals that seek to exploit OA mandates in publishing, selective OA journals such as eLife, PLoS Biology and Nature Communications charge APCs of $2500 [6], $3000 [7], and $5200 [8], respectively. These sums are astronomical for the majority of researchers. As written, Plan S could create a “pay-to-play” system, where only the best-funded researchers and institutions will be able to publish in the mandated journals, thus creating automatic inequality in publishing opportunities based on one’s geographic location and the size of one’s research budget.

Alarmingly, these astronomical numbers are not static, and are constantly increasing [9]. It has been argued that the true cost of a single paper in a selective journal such as eLife is $14,000 [10] (although eLife themselves suggest a substantially lower cost of £3,147 [11]), and, were Nature to flip to a fully open access model, the cost of papers in Nature would be expected to be substantially higher. It should be very simple to see that most researchers, institutions, and even funding bodies, could not afford a large volume of research published in a pure OA framework.

At some point it will be the cost of publishing rather than the quality of research or dissemination venue that will decide where research gets published, opening up a huge market for predatory publishers to exploit.

The problem of quality and sustainability

The obvious counter-argument to this cost-of-publishing problem is that one does not necessarily have to publish in selective OA journals such eLife, PLoS Biology and Nature Communications (to name three journals selected due to their visibility), and that there are other venues out there that do not charge quite so much to publish. However, Plan S, as written, will prevent researchers from publishing in 85% of currently existing journals, and there are simply not enough quality OA journals to fill the void [12].

Here, it is important to stress what we mean by quality: To many, a “high quality journal” immediately conjures up an image of a “high impact” journal. While quality journals may also have high impact factors, a high impact factor does not necessarily denote quality, nor does a low impact factor (for example in specialist fields with much smaller circulation), denote lack of quality.

A high quality journal, to us, is one with rigorous peer review and editorial oversight, where the publications provide a comprehensive study (as opposed to salami slicing), that makes a significant contribution to our knowledge of the field and checks for true novelty.

Despite its many problems, in a world where the number of scientific publications published per year is over 2.5 million (extrapolating from a 2015 report [13]) and the total global scientific output doubles every 9 years or so [14], peer review remains the most effective guard we have against bad science [15]. Insofar as it preserves some space for expertise and prevents both absolute relativism and a sort of scholarly oligarchy, peer review is also an important means for navigating the relationship between research and society [16].

Tying in with this, there is a serious quality control problem with moving from a subscription-based to an author-pays (Gold) OA model. In a subscription-based model, the onus is on the journal to publish material that will acquire subscribers willing to pay for access to that material, creating at least a minimal push for quality. A fully Gold OA framework can operate in two ways. One is to generate revenue for the journal by publishing as many papers as possible. The consequences of this can be drastic. For example, [“all 10 senior editors”, or “twenty out of the 96 board members”, the previous statement was corrected following a demand by MDPI CEO Franck Vazquez, -LS] of the journal Nutrients (published by MDPI), has recently resigned after allegedly being pushed to publish mediocre papers [17], presumably to hit journal publishing – and, in an author-pays arrangement, financial – targets. A similar problem occurred when Frontiers sacked 31 editors of the journals Frontiers in Medicine and Frontiers in Cardiovascular medicine, due to the editors raising concerns about publishing practices, which were described as being “designed to maximize the company’s profits, not the quality of the papers, and that this could harm patients” [18].

The other approach is to be selective, and create a desirable venue that the researchers strive to publish their best research in. At this point, the publisher can effectively set the price to publish there, which can either be the much higher costs associated with selective publishing in general, or even higher costs as a “quality premium” for being able to publish in a selective journal. This then creates the cost trap that severely restricts publishing options to researchers, based on the size of their research budget or the size of their institution or funders’ publishing budget.

OA publishers can be just as predatory and problematic as TA publishers, and simply moving to Gold OA and investing substantial public money into APCs will not resolve this problem.

Since only the rich can afford to publish under such an arrangement, Plan S risks creating a scholarly oligarchy. One would expect, at a minimum, that any publishing mandates based on the use of public funds for publishing costs would also discourage and disincentivize commercial platforms in favour of not-for-profit and academic society publishers, which invest the resources back into the academic community [19].

Following from this, it is a basic requirement of research having value that journals should provide sustainability, such that research is preserved for the next 10, 20, 50, or 100 years, and beyond. The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society was published for the first time on the 6th of March 1665, and can currently still be accessed for free online [20]. There are several established publishers, both from academic societies and commercial enterprises, that have demonstrated this scale of sustainability. However, in an exploding landscape of publishing, it is not clear that all the dissemination venues can maintain the same high sustainability standards (for an example of a journal suddenly ‘imploding’, see e.g. here [21]), and to cut researchers off from well-established and respected publishing venues without a clear and viable alternative that can support the tremendous amount of research being published today is clearly problematic.

The problem of exclusion

There is also the issue of the fact that research operates in a global environment, and we are a global community of researchers. Collaboration is key to progress, and researchers need to be able to exchange ideas and move between countries freely, and to share resources, samples, and equipment [22]. Collaborators need to be able to publish jointly, and not only within Europe or only among non-European countries. This will become very difficult once we start working with two separate publication systems, forcing certain countries to publish only Gold OA while the rest of the world remains using subscription journals.

Forcing scientists into full Gold OA publishing may sound sympathetic in the ears of certain policy makers, science funders or taxpayers, but in the very likely case that the rest of the world is reluctant to join, these plans will actually create many more problems than they solve.

Plan S/coAlition S puts forward a brave new plan for an open European research environment. However, what will happen if the rest of the world does not join us?

North America and Asia, for example, continue to be substantial producers of high quality research. This will severely complicate any EU-non-EU collaboration, and also lead to problems with the internationalisation of the EU. The cOAlition S countries will become utterly unattractive for PhD students and postdocs from abroad with academic ambitions, because they won’t be able to publish in existing journals of high standing. This is not only disastrous for their careers, but also devastating for the international position of the cOAlition S countries. The plans may also cause reluctance among scientists on both sides to perform service activities for ‘the other system’ on the basis of reciprocity. Quite obviously, in a system in which the research world is divided into exclusive coalitions, the international standing, rankings and respect for scientists living in the cOAlition S countries will fall.

There is tremendous danger in preventing researchers from publishing in 85% of journals (including the best journals for many fields), without having provided viable alternatives. In addition, should these journals continue to maintain the status quo, accepting submissions from North America and Asia and other parts of the world rather than flipping their business models, the cost to Europe could be tremendous. Either we would have to anyhow double pay, both to publish in fully open access venues and to read subscription journals, at tremendous financial cost, or we would cancel our subscriptions to those journals, and then be cut off from the global research community. Going this alone without a concerted global push is incredibly risky, and could put European researchers out in the cold.

The problem of violating academic freedom

Finally, while one could argue that funding agencies have the right to dictate how their funds are spent, Plan S clearly violates one of the basic tenets of academic freedom – the freedom to publish research results in venues of the researcher’s choosing. Plan S does not just mandate open access, but also mandates the form of open access, strongly favouring Gold as the desired model, and banning hybrid publications (even in society journals!).

Although Plan S does allow that cOAlition-S-funded research may be published “on compliant Open Access Platforms,” there are no clear criteria of what that category includes and excludes. Instead, Plan S merely promises that,

“The [cOAlition-S] Funders will ensure jointly the establishment of robust criteria and requirements for the services that compliant high quality Open Access journals and Open Access platforms must provide.”

Further, Plan S suggests that all research must be published under an open license, with a preference for the CC-BY license, and that, “In all cases, the license applied should fulfil the requirements defined by the Berlin Declaration.” This requirement severely limits the scope of what Peter Suber has called libre OA [23], which is a broad swath of open options. Neither the CC-BY license nor the Berlin Declaration allow researchers to restrict access to non-commercial uses, for instance. Several authors of this article, for moral reasons, are strong proponents of CC-BY-NC rather than CC-BY licenses on their work, in order to restrict for-profit commercial exploitation of publicly funded research. Mandated open access, with heavy restrictions on the form this open access can take, combined with mandates on the form of licensing, severely impinge on researchers’ freedom to disseminate their research and to limit how their research will be used and by whom [24, 25].

In his preamble to Plan S, Marc Schiltz, President of Science Europe, seems to ignore the fact that today’s OA ecosystem provides researchers many options to disseminate publications and data in ways that respect our academic freedom. He writes:

“We recognise that researchers need to be given a maximum of freedom to choose the proper venue for publishing their results and that in some jurisdictions this freedom may be covered by a legal or constitutional protection. However, our collective duty of care is for the science system as a whole, and researchers must realise that they are doing a gross disservice to the institution of science if they continue to report their outcomes in publications that will be locked behind paywalls. [26]”

Here, Schiltz ignores the important difference between gratis and libre OA [27]. Recognizing this distinction, where gratis OA removes the paywall and libre OA removes some (but not necessarily all) restrictions on re-use, is vital to respecting academic freedom. The choice Schiltz gives researchers – publish without paywalls or violate your “collective duty of care” to the institution of “science as a whole” – is a false dilemma, especially as instantiated by Plan S. For instance, under the existing ecosystem, a researcher could publish an article in a TA journal, yet deposit a version of the article in an institutional repository without a paywall (Green OA). This would effectively remove the paywall, yet would violate the terms of Plan S. Alternatively, under the existing ecosystem, a researcher could publish in a professional society journal that publishes articles OA, without imposing any APCs on the author (Platinum or Diamond OA).

This, too, would violate the terms of Plan S. Alternatively, a researcher could make use of an institutional repository to provide gratis OA to a publication, yet apply a variety of libre OA licenses [28]. Unless the license the researcher chooses is CC-BY, it is unclear how this would be permitted under the terms of Plan S.

Finally, as researchers, we feel several obligations that include, but are not limited to, the duty to care for the institution of science as a whole. We feel obligations to various researchers, both individuals and groups, which are mere parts of science-as-a-whole. We feel obligations to society, including not only society as a whole, but also to various groups and individual that make up society as a whole. We also feel obligations to our students, both as individuals and as a group. Many of us also feel obligations to ourselves, to our families, and to our professors to publish the best work we can in the highest quality venues we can manage. Making our research freely available (gratis OA) is compatible with all of these obligations, but violates Plan S. We are also open to removing some restrictions to the re-use of our data and research (libre OA). But Plan S both restricts the venues in which we may publish and mandates the restrictions we may place on the re-use of our research. Plan S thus clearly – and needlessly – violates our academic freedom.

Ideas for solutions

(1) One possible solution would be to convince all subscription (TA) journals to make all papers fully OA after an embargo period of 6-12 months, without APCs. In this environment, libraries would still buy subscriptions to allow scientists to catch up with the most recent developments, and the broader public would have access to all research without a paywall (but with a slight delay). While this plan does not provide immediate access to everyone, it is a safe and easy solution that would be beneficial for most stakeholders. Under this model, most publications would be ready by scientists in the first 6-12 months after publication, and after the embargo period is over, no further costs should be accrued to access a scientific paper.

In a modification of Plan S, rather than an indiscriminate blanket ban on all non-pure Gold OA journals, it would then be possible to exclude any (non-society) journals that won’t accept this policy from the list of ‘allowed’ journals. This will likely still result in some journals being excluded as possible publication venues, but is a smaller infringement on academic freedom, and could become an acceptable situation for most researchers and a model to which any journal can easily adapt without compromising on quality.

We note that according to Robert-Jan Smits, the European Commission’s Open Access Envoy, even an embargo period of 6-12 months is ‘unacceptable’ [29], but he does not explain why exactly that should be the case.

Very recently, Belgium accepted a new law following this exact 6-12 month embargo model. This embargo period is intended to ‘give authors the chance to publish their papers in renowned journals, and prevents that publishers are damaged by a loss in income from subscriptions’, as is the opinion of Peeters’ cabinet.” [30]

(2) Another model, which can be implemented in conjunction with point (1), is a mandate on depositing preprints in appropriate online repositories (Green OA), similar to the Open Access requirements of the US National Institutes of Health [31]. This is the model frequently employed by scientists to meet funders’ Open Access requirements. These are then easily searchable using a range of search tools, including (but not limited to), most easily, Google Scholar. This is a solution with great benefits to the reader and limited risks to the author, as it allows for rapid early-stage dissemination of research, the provision of real time feedback to the authors, while opening up research to the scientific community and general public much faster than waiting for the very long publication time scales inherent to some journals.

The one thing that does need to be taken into account with preprint servers is that they do redirect citations from the final published versions of articles [32]. While we would prefer that bibliometrics not be used as a tool for assessing individual researchers and research-active entities, in any system that does use bibliometrics, this redirection of citations should be taken into account and both citations to the preprint and to the actual paper considered. Overall, this, once again, seems to be a solution the Belgian government is in favour of [33]. One could even consider working with a legal international repository from which all available scientific papers could be downloaded after a certain embargo period.

(3) We note here also that more and more reputable publishers are now adding high quality open access publications to their repertoire of journals. In particular, we encourage fully open access journals published by scientific societies. A brief (but by no means exclusive) list of examples of such journals include ACS Central Science [34], ACS Omega [35], Chemical Science [36], RSC Advances [37], the Royal Society journals Open Biology [38] and Open Science [39], IUCrJ [40] and eLife [41], among others. A move to a fully open access landscape is clearly going to become much easier when there are more journals that can guarantee the same level of quality control and sustainability as current reputable subscription journals, as venues to disseminate one’s work. It may be a slower transition, but making this transition in an ecosystem that supports it does not infringe on academic freedom as Plan S does.

Clearly, the overall march towards Open Knowledge Practices seems inevitable, as well as desirable, as researcher consciousness about the means of research dissemination, the possibilities, and the important ethical issues surrounding closed science increases. We must be careful to encourage this march in a way that does not replace one problem with another.

(4) Finally, the debate about Open Access, and APC, ignores the Diamond (also known as Platinum) model of OA publication. Diamond publication is a fully sponsored mode of publication, in which neither author nor publisher pays, but rather, the journals are funded by a third party sponsor. An example of Diamond OA is provided by the Beilstein Journals, all publications for which are covered by the non-profit Beilstein Institute in Germany [42]. Similarly, there is no fee for publication in ACS Central Science, and all publication costs are covered by the American Chemical Society [43]. It is important to ensure the moral and ethical integrity of that sponsor. But, when performed in an ethically uncompromised framework, this would be an ideal model for publications by scientific societies, whose journals could then either be sponsored by funders and other donors. In such a framework, rather than simply transferring costs from readers to authors, while allowing questionable journals to flourish and exploit APC, quality control can be ensured by financially supporting high quality not-for-profit publications. Would this not be a much braver step for European and National funders to mandate, than a push for pure Gold OA?

Conclusions

In summary, all authors of this piece are strong proponents of Open Knowledge Practices and would like to see a push towards an open research ecosystem. However, moving toward an OA knowledge ecosystem should be balanced with challenging questions of academic freedom and academic equity in terms of access to resources and ability to publish, acknowledging also that not all Open Access publishers are equal in terms of rigour and publishing morality. Banning hybrid publications (even in society journals), the short shrift given to Green OA, the risk of creating a complete dichotomy of the global scientific society and the lack of respect for researchers’ academic freedom in Europe constitute the most disturbing aspects of Plan S. Had the plan been a strong, yet fair, push towards an open ecosystem in a way that is economically sustainable and provides author choice in how the research is made openly accessible, we would have quickly joined the chorus of applause and supported this plan fully. However, the plan, as currently written, is simply a mechanism by which to shift the cost of publication from one pot of money to another, while significantly restricting author choice in publications in Europe and with many unwanted side effects that put the European academic research landscape at severe risk. It should therefore be clear why we (and countless colleagues with whom we have discussed this topic) are, to put it mildly, severely alarmed at the consequences this could have for the European research landscape, and Europe’s future competitiveness as a global research and innovation heavyweight.

Authors

Lynn Kamerlin is a Professor of Biochemistry at Uppsala University, a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry. She is also the former Chair of the Young Academy of Europe, and a former ERC grantee. She is an open science advocate, and has been involved in many activities to promote Open Science, including serving on working groups and expert groups at the European Commission, both as an invited speaker and as a participant of the group. She currently serves as a member of the EU Expert Group on Indicators for Researchers’ Engagement with Open Science and its Impacts. She is also a co-author of the Bratislava Declaration for Young Researchers. Finally, she currently serves on the Editorial Board of the journal Electronic Structure, on the Editorial Advisory Boards of the journals ACS Catalysis, the Journal of Physical Chemistry, and ACS Omega, and is a member of the advisory board of F1000Research

Pernilla Wittung-Stafshede is a Professor and Chair of Chemical Biology division at the Biology and Biological Engineering Department at Chalmers University of Technology. Her research centres around protein biophysics, with current focus on mechanisms of copper transport proteins and cross-reactivity in amyloid formation. She spent 10 years as faculty at universities in USA before being recruited back to Sweden ten years ago. She is Wallenberg Scholar and a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of the Sciences. She is a member of the Biophysical Society Council and serves as an editor of Quaternary Reviews of Biophysics Discovery (QRB-D). At Chalmers,

Pernilla Wittung-Stafshede is a Professor and Chair of Chemical Biology division at the Biology and Biological Engineering Department at Chalmers University of Technology. Her research centres around protein biophysics, with current focus on mechanisms of copper transport proteins and cross-reactivity in amyloid formation. She spent 10 years as faculty at universities in USA before being recruited back to Sweden ten years ago. She is Wallenberg Scholar and a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of the Sciences. She is a member of the Biophysical Society Council and serves as an editor of Quaternary Reviews of Biophysics Discovery (QRB-D). At Chalmers,

Abhishek Dey, PhD

Abhishek Dey, PhD

Associate Professor, Chemistry. Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) Research Website

Associate Editor, ACS Catalysis, EAB Chemical Communications, Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry, EAB Inorganic Chemistry (2013-2016)

Stephen A. Wells is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bath with multidisciplinary interests in computational chemistry, mineral physics and protein structural biology. After studying Natural Sciences, followed by a PhD in Earth Sciences, at the University of Cambridge, he has worked at the Royal Institution, at Arizona State University, at Warwick University, and at Bath in the departments of Physics, Chemistry, and (currently) Chemical Engineering.

Stephen A. Wells is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bath with multidisciplinary interests in computational chemistry, mineral physics and protein structural biology. After studying Natural Sciences, followed by a PhD in Earth Sciences, at the University of Cambridge, he has worked at the Royal Institution, at Arizona State University, at Warwick University, and at Bath in the departments of Physics, Chemistry, and (currently) Chemical Engineering.

Maja Gruden is associate professor in Inorganic chemistry at the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her main research interest is accurate computing of ground and excited state properties of transition metal complexes by DFT and development and extension of multireference DFT techniques. She was Coordinator for International Collaboration at Faculty of Chemistry University of Belgrade, 2011-2013, and Vice dean for science and international cooperation at Faculty of Chemistry University of Belgrade, 2013-2015. She is a supporter of OA publishing.

Maja Gruden is associate professor in Inorganic chemistry at the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her main research interest is accurate computing of ground and excited state properties of transition metal complexes by DFT and development and extension of multireference DFT techniques. She was Coordinator for International Collaboration at Faculty of Chemistry University of Belgrade, 2011-2013, and Vice dean for science and international cooperation at Faculty of Chemistry University of Belgrade, 2013-2015. She is a supporter of OA publishing.

Marc W. van der Kamp (ORCID) is a BBSRC David Phillips Research Fellow at the University of Bristol (School of Biochemistry). He is a supporter of open access publishing and open source code. He has over 40 publications in the area of biomolecular simulation and regularly reviews for high-impact journals. He has recently established an independent group (2 Post-docs, 2 full & two co-supervised PhD students) and currently holds 3 research grants as PI (£1.5M; aside from PhD studentships). He is a member of the CCPBioSim (Collaborative Computational Project for Biomolecular Simulation) and HECBioSim management groups, and is an advocate for equality, diversity and inclusion (member of the EDI departmental committee; contributed to University and departmental Athena SWAN Award applications).

Bas de Bruin is professor in organometallic chemistry & homogeneous catalysis at the Van ‘t Hoff Institute for Molecular Sciences (HIMS) at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). His research interests are in organometallic chemistry & catalysis, with a current emphasis on development of new catalytic reactions through metalloradical catalysis. He is a laureate of ERC & NWO VIDI, VICI & TOP grants. He publishes in, and reviews for several (society) journals, such as the ACS and Wiley. He was on the editorial board of EurJIC, the editorial advisory board of Organometallics and is currently on the editorial advisory board of ACS Catalysis. He is a supporter of OA publishing, and regularly tried to convince the chemistry society journals to adapt a suitable OA publication model.

Bas de Bruin is professor in organometallic chemistry & homogeneous catalysis at the Van ‘t Hoff Institute for Molecular Sciences (HIMS) at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). His research interests are in organometallic chemistry & catalysis, with a current emphasis on development of new catalytic reactions through metalloradical catalysis. He is a laureate of ERC & NWO VIDI, VICI & TOP grants. He publishes in, and reviews for several (society) journals, such as the ACS and Wiley. He was on the editorial board of EurJIC, the editorial advisory board of Organometallics and is currently on the editorial advisory board of ACS Catalysis. He is a supporter of OA publishing, and regularly tried to convince the chemistry society journals to adapt a suitable OA publication model.

Britt Holbrook (ORCID), Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities, New Jersey Institute of Technology, USA, earned his PhD in philosophy from Emory University in 2004. His postdoctoral research at the University of North Texas explored the use of broader societal impacts criteria in the peer review of grant proposals at both US and European funding agencies, philosophical and policy issues surrounding open access, and the development of quantitative metrics of broader impacts. Holbrook is currently serving as a member of the European Commission Expert Group on Indicators for Researchers’ Engagement with Open Science and its Impacts. In addition to his work on science and technology policy, Holbrook conducts research on the ethics of science, engineering, and technology. He was Editor in Chief of Ethics, Science, Technology, and Engineering: A Global Resource(Macmillan Reference). As a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Committee on Scientific Freedom and Responsibility (2012 – 2018), Holbrook was one of the co-authors of the AAAS Statement on Scientific Freedom and Responsibility.

Britt Holbrook (ORCID), Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities, New Jersey Institute of Technology, USA, earned his PhD in philosophy from Emory University in 2004. His postdoctoral research at the University of North Texas explored the use of broader societal impacts criteria in the peer review of grant proposals at both US and European funding agencies, philosophical and policy issues surrounding open access, and the development of quantitative metrics of broader impacts. Holbrook is currently serving as a member of the European Commission Expert Group on Indicators for Researchers’ Engagement with Open Science and its Impacts. In addition to his work on science and technology policy, Holbrook conducts research on the ethics of science, engineering, and technology. He was Editor in Chief of Ethics, Science, Technology, and Engineering: A Global Resource(Macmillan Reference). As a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Committee on Scientific Freedom and Responsibility (2012 – 2018), Holbrook was one of the co-authors of the AAAS Statement on Scientific Freedom and Responsibility.

Sam Hay (ORCID) is a Senior Lecturer in the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology and School of Chemistry at the University of Manchester (UK). His research interests are in biophysical chemistry, with a focus on enzyme catalysis and quantum biology. He is a former BBSRC David Phillips Research Fellow and a member of a number of societies including the RSC, ACS and Biochemical Society. He has active collaborations across Europe, North America, Asia and Australasia and regularly publishes in, and reviews for a number of society and non-society journals. He is an advocate of data sharing, open source software and pragmatic OA publishing.

Sam Hay (ORCID) is a Senior Lecturer in the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology and School of Chemistry at the University of Manchester (UK). His research interests are in biophysical chemistry, with a focus on enzyme catalysis and quantum biology. He is a former BBSRC David Phillips Research Fellow and a member of a number of societies including the RSC, ACS and Biochemical Society. He has active collaborations across Europe, North America, Asia and Australasia and regularly publishes in, and reviews for a number of society and non-society journals. He is an advocate of data sharing, open source software and pragmatic OA publishing.

References

- Full text of Plan S and related documents can be found here: https://www.scienceeurope.org/coalition-s/. See also ‘Plan S’ and ‘cOAlition S’ – Accelerating the transition to full and immediate Open Access to scientific publications. European Commission Statement, 4th September 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/moedas/announcements/plan-s-and-coalition-s-accelerating-transition-full-and-immediate-open-access-scientific_en

- Open Future. An explosion of openness is about to hit scientific publishing. The Economist, 7th September 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/09/07/an-explosion-of-openness-is-about-to-hit-scientific-publishing

- Holly Else. Radical open-access plan could spell end to journal subscriptions. Nature, 4th September 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-06178-7?amp;utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+nature%2Frss%2Fcurrent+%28Nature+-+Issue%29

- Martin Enserink. European funders seek to end reign of paywalled journals. Science, 7th September 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/361/6406/957

- Éanna Kelly. Hope – and a welter of concerns – greets Europe’s radical open access plan. Science | Business, 6th September 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://sciencebusiness.net/news/hope-and-welter-concerns-greets-europes-radical-open-access-plan

- Mark Patterson. Setting a free for publication. eLife, 29th September 2016. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://elifesciences.org/inside-elife/b6365b76/setting-a-fee-for-publication

- PLoS Publication Fees. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.plos.org/publication-fees

- Article Processing Charges. Nature Communications. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.nature.com/ncomms/about/article-processing-charges

- Björn Brembs. How Gold Open Access may make things worse. Björn Brembs Blog, 7th April 2016 (with updates). Retrieved 8th September 2018. http://bjoern.brembs.net/2016/04/how-gold-open-access-may-make-things-worse/

- Kent. Anderson. How much does it cost eLife to publish an article? The Scholarly Kitchen, 18th August 2014. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/08/18/how-much-does-it-cost-elife-to-publish-an-article/

- Mark Patterson. What it costs to publish. eLife, 11th August 2016. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://elifesciences.org/inside-elife/a058ec77/what-it-costs-to-publish

- Michael Jubb (Chair). Andrew Plume, Stephanie Oeben and Lydia Brammer (Elsevier). Rob Johnson and Cihan Bütün (Research Consulting). Stephen Pinfield (University of Sheffield). Monitoring the transition to Open Access. Universities UK, December 2017. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2017/monitoring-transition-open-access-2017.pdf

- Mark Ware and Michael Mabe. The STM report: An overview of scientific and scholarly publishing. International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers, 2015. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.stm-assoc.org/2015_02_20_STM_Report_2015.pdf

- Richard van Noorden. Global scientific output doubles every nine years. Nature news blog, 7th May 2014. Retrieved 8th September 2018. http://blogs.nature.com/news/2014/05/global-scientific-output-doubles-every-nine-years.html

- The Conversation. The peer review system has flaws. But it’s still a barrier to bad science. 20th September 2017. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://theconversation.com/the-peer-review-system-has-flaws-but-its-still-a-barrier-to-bad-science-84223

- Holbrook, J. Britt. “Peer review, interdisciplinarity, and serendipity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, 2nd edition. Robert Frodeman, Julie Thompson Klein, Roberto C. S. Pacheco, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 485-97.

- Jop de Vrieze. Open-access journal editors resign after alleged pressure to publish mediocre papers. Science, 4th September 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/09/open-access-editors-resign-after-alleged-pressure-publish-mediocre-papers

- Martin Enserink. Open-access publisher sacks 31 editors amid fierce row over independence. Science, 20th May 2015. Retrieved 8th September 2018. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/05/open-access-publisher-sacks-31-editors-amid-fierce-row-over-independence

- Plan S does also allow for publication in “compliant” OA platforms in addition to Gold OA journals, but this presents its own problems, which we discuss, below.

- Harry Oldenburg. Epistle dedicatory. Philosophical Transactions 1 (1665), DOI: 10.1098/rstl.1665.0001.

- Colleen Flaherty. A journal implodes. Inside Higher Ed., 15th June 2018. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/06/15/promising-open-access-anthropology-journal-moves-modified-subscription-service-amid

- Sugimoto, Cassidy R., Nicolas Robinson-Garcia, and Rodrigo Costas. “Towards a global scientific brain: Indicators of researcher mobility using co-affiliation data.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.06499 (2016). https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1609/1609.06499.pdf

- Peter Suber. Gratis and libre open access. SPARC Open Access Newsletter, issue #124 August 2, 2008. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/4322580/suber_oagratis.html?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, accessed 9 September 2018.

- Rick Andersson. Open access and academic freedom. Inside Higher Ed, 15th December 2015. Retrieved 8th September 2018.

- https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2015/12/15/mandatory-open-access-publishing-can-impair-academic-freedom-essay. As Andersson also points out, mandating that authors retain copyrights to their work, but then also mandating that the work be disseminated under a CC-BY license, which removes all control the author has over how the work will be used, are inconsistent.

- David Crotty. Licensing controversy – Balancing author rights with societal good. The Scholarly Kitchen, 12th February 2013. Retrieved 8th September 2018. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/02/12/licensing-controversy-balancing-author-rights-with-societal-good/

- Marc Schiltz. Science Without Publication Paywalls a Preamble to: cOAlition S for the Realisation of Full and Immediate Open Access, 4 September 2018. https://www.scienceeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/cOAlitionS_Preamble.pdf

- Suber 2008, op. cit.

- For an example of an institutional repository that allows researchers many options for the license applied to each individual deposit, see Humanities Commons, which is supported by the Modern Language Association (MLA): https://hcommons.org/.

- Frans van Heest in Science Guide. Robert-Jan Smits bespeurt veel hypocrisie bij open access. 23th July 2018. Retrieved 9th September 2018. https://www.scienceguide.nl/2018/07/robert-jan-smits-bespeurt-veel-hypocrisie-bij-open-access/

- Lotte Alsteens in dS De Standaard. Ook nieuwe Belgische wet forceert ‘open’ wetenschap. 5th September 2018. Retrieved 9th September 2018. http://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20180905_03703636

- NIH public access policy details. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://publicaccess.nih.gov/policy.htm

- Phil David. Journals lose citations to preprint servers. 21st May 2018. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/05/21/journals-lose-citations-preprint-servers-repositories/

- Belgisch Staatsblad/Moniteur Belge, N. 209, 188e Jaargang. Art. 29, page 686691. 9th September 2018. Retrieved 10th September 2018. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi/article.pl?urlimage=%2Fmopdf%2F2018%2F09%2F05_1.pdf%23Page81&caller=summary&language=fr&pub_date=2018-09-05&numac=2018031589

- ACS Central Science. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://pubs.acs.org/journal/acscii

- ACS Omega. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://pubs.acs.org/journal/acsodf

- Chemical Science. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/journals/journalissues/sc#!recentarticles&adv

- RSC Advances. Retrieved 10th September 2018. http://www.rsc.org/journals-books-databases/about-journals/rsc-advances/

- Open Biology. Retrieved 10th September 2018. http://rsob.royalsocietypublishing.org

- Royal Society Open Science. Retrieved 10th September 2018. http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org

- IUCrJ. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://journals.iucr.org/m/

- eLife. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://elifesciences.org/

- Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry. Platinum Open Access. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://www.beilstein-journals.org/bjoc/openAccess

- ACS Publications Open Access. Retrieved 10th September 2018. https://pubs.acs.org/page/4authors/openaccess/index.html#acscii

The way to go is very easy no need for any plan S, B, D or C

It is enough high impact journals start playing clean and that open peer review with access to original becomes a requirement in any journal

LikeLike

Also note that I distinguish between high quality and high impact. Some great journals have high IF, some less great journals have high IF, some great journals (especially in specialist and nice areas) have low IF. It’s sometimes an indicator but not always.

LikeLike

I’d love to have your feedback on the ideas on how to cut the Gordian knot that is open access put forward in this new preprint https://zenodo.org/record/1410000#.W5dXV1rRahD

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this link! I am currently at a conference and need to pay attention to the (excellent) speakers, but will read your link carefully as soon as I come home!

LikeLike

I read it now. This is very good, and we share a common love of preprints!!

LikeLike

I had a short exchange with Dr Kamerlin on Twitter a week or so ago. We arrived at opposite conclusions: hers was that Plan S would inadvertently restrict publishing in certain journals. My conclusion was that restricting publication in certain journals was the whole point of Plan S, and might not necessarily be a bad thing.

While I agree with the fundamental aims of Plan S, I see a few issues 1) the actual implementation of Plan S, 2) whether Plan S can address the fundamental issues with scientific publishing, and 3) the continuing myth of the “quality” journal.

And while I agree most of the points forwarded by Dr Kamerlin and colleagues, I have issues with their arguments too; but it is vital for science and the business of publishing that these opinions are heard, weighed, and distributed widely – even if people don’t agree with the message.

1) The actual implementation of Plan S

Understanding the proposed implementation of Plan S as I do now, both Dr Kamerlin and my own conclusions as to the effects of Plan S are possible outcomes; and there lies the issue – I don’t think anyone really knows what will happen when Plan S is implemented, and that is NOT a good thing. As I understand it, Plan S is a response to the lacklustre uptake of Open Access, making it in essence a band-aid on top of a band-aid on top of a festering wound. Right now, we have no idea whether Plan S goes too far, or whether it doesn’t go far enough (see Dr Kamerlin et al’s comments to diamond OA).

Publishers’ possible responses to Plan S

While Plan S seems, on the surface, a transformational idea; it is naive to assume that scientific publishing happens in a vacuum. Publishers will quickly capitalise on any opportunity to make more money, and more power to them: if I were a RELX shareholder I would expect them to make decisions and strategic plans to increase profitability and my dividend payout. Scientific publishers aren’t blind (well, perhaps only blind if it helps their bottom line), nor are they stupid: most, if not all of them will already have contingency plans for Plan S-like scenarios. When Plan S is set in motion, publishers will quickly move to counter negative effects to their bottom lines. This is where I strongly agree with Dr Kamerlin et al’s idea of “…shift[ing] the cost of publication from one pot of money to another…”

So looking at Plan S, I fully expect journals will use this as a carte blanche to increase article APCs, citing reasons like ‘offsetting operational expenses’ and ‘ecosystem sustainability’ and other econobabble. Plan S has a proposed cap on APCs, but doesn’t specify this cap (yet). I will bet you my slippers and a half-eaten biscuit that publishers will raise all APCs up to exactly this cap as soon as it is known. I am as baffled as the authors of the Open Letter are in the relative ignoring of Green OA in Plan S – an accidental omission or an echo of the slithering tongues of Frontiers and Elsevier’s well-documented lobbying activities in the European Commission?

This helps nobody except the publishers, and is probably the worst outcome for researchers as it makes publishing in the “”right”” journals prohibitively expensive for those without funds to publish – and one might argue that these are the voices already marginalised in scientific discourse; such as ECRs or researchers from LMICs. Those with the biggest pots of money will get to publish the most, which will get them more grants, etc. Weren’t we meant to break a cycle instead of reinforcing it?

2) Can Plan S address the fundamental issues with scientific publishing?

A journal is only as good as its editorial and reviewer team. While I tend to agree with Dr Kamerlin et al’s analysis that Plan S can, in principle, restricts academic freedom, I’ve been wondering since my first Twitter exchange with Dr Kamerlin whether this is a good, bad or neutral thing.

Restricting access and academic freedom

Depending, again, on the implementation of Plan S and publishers’ reactions to this, we might end up restricting publishing in certain journals that aren’t willing to move forward on research transparency and Open Access. This is where Dr Kamerlin and I bump heads: there is a case to be made that this is a ‘restriction of academic freedom’; but there is also a case to be made that this is unavoidable, possibly even beneficial collateral damage. Is restricting freedom always a bad thing? In the case of firearms, drugs and Jason Donovan albums there is a definite case to be made in favour of restriction and in my opinion the same goes for journals that choose to insist on outdated publication practices. For my part, I think that upholding a status quo is a far bigger limitation on academic freedom, which includes the freedom to publish non-novel ideas such as replications. Using grand ideas as academic freedom to argue against Plan S can only stand if we consider how the current situation is limiting our academic freedom: we have the freedom to publish sexy findings in untransparent, glamorous paywalled journals with high impact factors, or we can forget about our careers. Oh, and we can’t even share our own papers. How is that academic freedom?

3) The myth of the “quality journal”

The Open Letter refers to ‘quality venues’ – the authors rightfully disown the Impact factor, yet fail the address heterogeneity within journal quality. Thinking of a journal ‘brand’ as an indicator of quality is thus a dangerous oversimplification: but publishers are fully geared towards marketing their ‘journal brand’ as an indicator of quality; with the accompanying impact factor as “proof”.

A journal is not one thing – it is many things, and at the heart of “quality control” are editors and peer reviewers, many of whom are emphatically NOT part of that journal per se, as they are often unpaid volunteers. A journal is, quality wise, only as good as its editorial team and reviewers. A paper isn’t a quality paper because it’s in Nature or the Lancet, it’s a quality paper because it was expertly reviewed by our colleagues and edited by one of our excellent colleagues. That team might work for the Liechtensteinian Journal of Applied Mathematics and Animal Husbandry too – and perform admirably in that journal as well.

Famous journals sometimes publish junk (remember Wakefield in the Lancet?), while “lower” journals sometimes publish excellent and ground-breaking studies. Without open peer reviews, more transparency on rejections and actual rather than theoretical adherence to guidelines, neither Dr Kamerlin et al’s proposed solutions nor Plan S will improve the quality of scientific publishing. We need to seriously think about our relationship to journals if we are to improve scientific publishing, since publishers will mercilessly exploit our idea of what constitutes a “quality” journal, and will do anything to protect their brands.

Exaggerating the point somewhat, it seems like Dr Kamerlin et al are invoking academic freedom as an argument to retain their right to publish in what they consider “quality journals” – a rather heavy-handed approach, and in my opinion most, if not all, of Dr Kamerlin et al’s proposed solutions will maintain the current status quo as they hinge on an arbitrary – and much exploited and abused – definition of the “quality journal”.

As a side note, the letter also refers to ‘limited novelty’ – being a psychologist, my own field is in the midst of a reproducibility crisis; and my opinion is that the concept of ‘limited novelty’ should be buried as soon as possible. This absurd drive for tabloid-style exciting findings is what got us into the reproducibility crisis in the first place, and it fuels the hype cycle that in turn causes us to have gross misconceptions of what ‘good’ or ‘impactful’ journals are.

Moreover, Dr Kamerlin et al see no issues with 6-12 month embargoes. The implicit reasoning is, I think, that scientific papers are read by scientists, which may very well be the case in Dr Kamerlin’s field. However, I’ve spoken to countless clinicians whose professional societies expect them to stay up to date, as evidence-based medicine demands. There is a steady stream of reviews and meta-analyses which inform clinical practice whether a particular approach is beneficial and should be adopted, or whether is turns out to be useless or even harmful. That is information that is needed now, and not after a leisurely 6-12 months. Having to tell patients that they’ll be treated according to the newest insights in 6-12 months instead of tomorrow feels vaguely unethical to me. Solution 1) as proposed is, as such, unacceptable in my opinion.

Finally, I think my issues with both Plan S and Dr Kamerlin et al’s open letter are the same: neither address fundamental issues in academic publishing: perverse incentives to publish as many “novel” papers as possible in “quality” journals, the published paper as academic currency for promotions and status, and shameless profiteering by publishers whose token efforts to transition to Open Science and transparency are perfunctory at best and misleading at worst.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good points.

LikeLike

Well, I agree with much of this comment.

In our defense, the post was not trying to tackle all the fundamental issues in scholarly publishing, but only to serve as a reaction to Plan S.

I don’t think the argument against our argument on academic freedom is well-formed. We can agree that restricting freedom is not always bad (as in the case of guns); but that is largely irrelevant to the claim that Plan S infringes on academic freedom. It doesn’t follow from the fact that some freedoms should be limited that academic freedom should be limited in the way Plan S implies.

Not all freedoms are created equal, and academic freedom should be limited as little as possible. The idea that individual academics ought to sacrifice their freedom for the good of science — which is an idea that the Preamble states clearly — is unethical, in my opinion. First of all, it ignores the fact that not all those affected by Plan S are scientists; or, worse, it supposes that treating all the non-scientists as part of science and forcing them to sacrifice their academic freedom for the good of science is unproblematic. Second, it presupposes an idea that I would call ‘the unity of knowledge’. This idea suggests that individual researchers are not all that important, because what’s of primary importance is attaining as much knowledge as possible. Because knowledge is unified, it’s the collective effort that matters, rather than individual efforts. But that’s a very scientistic understanding of knowledge. Can you imagine anyone suggesting that individual poets aren’t important, because it’s all about poetry as a whole?

I don’t at all want to alienate my scientist friends here. Probably many scientists don’t buy into the unity of knowledge or believe that their individual contributions to science are irrelevant. But Plan S is just part of what feels like — from the perspective of a non-scientist — a concerted effort to suggest that all scholarship needs to be scientific and conform to scientific norms. Maybe lots of scientists have no problem with CC-BY licenses. But lots of folks from the arts and humanities do have problems with CC-BY. Maybe lots of scientists want to make sure that every study undertaken is replicable. But that’s really just not a thing in the humanities, where simply replicating something someone else did would be more likely to fall under plagiarism than be laudable. Everyone doing science policy — as if ‘science’ were a unified thing with no field-specific differences, and then forgetting altogether about the arts and humanities and large chunks of the social sciences — needs to take a step back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t get the argument that diamond/platinum OA is not compliant with Plan S – as long as the journal is fully OA, how does it matter whether they charge a fee or not?

LikeLike

There can be issues with licensing (CC-BY demanded) so diamond/platinum is not automatically compliant with Plan S. In general I think it would have been braver to say that we will now support high quality publishing platforms (Beilstein/ACS Central Science model) rather than still talking about APCs and paid-Gold.

LikeLike

Well sure if they have a license mismatch, but the article is not at all clear on this. Most diamond journals that I know use the CC-BY license already.

LikeLike

I actually agree with Toma Susi that we should have been clearer on this point about Diamond OA (and I take responsibility for not being clearer myself). Rather than saying that Diamond OA is not Plan S compliant, we should have said that Diamond OA that uses anything other than CC-BY or its equivalent appears not to be Plan S compliant. But if that’s correct, I still contend that Plan S violates academic freedom.

LikeLike

Lots of discussion on Twitter for this blog post: https://twitter.com/kamerlinlab/status/1039385135857258496

LikeLike

Research institutions should be responsible for publishing scientific journals, where quality and scientific value are the main goal, not profit only, as it is for both subscription based and OA publishers. Just take a closer look at all the junk published in so called serious OA journals via e.g. Science Direct/Elsevier. They are supposed to be serious due to their membership in DOAJ, but they are sailing under false flag. Research institutions and funding agencies should be much more strict regarding where their researchers can publish, but to open up only for OA journals will only make it worse. And it is a wild west already!

LikeLike

I wholeheartedly agree that forcing us to publish only open access is not the way to go. Let us be the judge on how and where to publish our work!

LikeLike

Pingback: Presunti stacanovisti - Ocasapiens - Blog - Repubblica.it

I am writing this on behalf of Prof. Arieh Warshel from the University of Southern California, who supports our letters and asked me to sign it on his behalf.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These concerns are pretty valid, I hope there’s going to be iterations of Plan S addressing at least some of your concerns. The for profit vs not for-profit discussion is also quite interesting, we need to keep in mind that competition drives innovation and not for profits struggled to do just that (think about plos and the Aperta fiasco).

Also: this would have been a much better read without Leonid’s usual personal crusade against a certain publisher. It devalues the rest of the post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: What we read this week (14 September 2018) – BMJ Digital

Pingback: Plan S – J. Britt Holbrook

Reblogged this on jbrittholbrook and commented:

Happy to have contributed to this. If you have comments, please post below the original at For Better Science!

LikeLike

Pingback: Plan S: Antwort auf die Kritik | wisspub.net

Pingback: Plan S – response to alternatives proposed by Kamerlin et al. | Innovations in Scholarly Communication

There are a several fundamental problems with the basis for Plan S and the choice of discussants in advocating the policy. Scientific publishing can always be improved upon, but I would argue it is explicitly not the appropriate role of scientific funders to try to drive disruptions in the scientific publishing model via clauses in funding agreements. Secondly, I would argue that the appropriate means of scholarly dissemination should be decided by the scholarly communities involved (with appropriate considerations for public interest). Having formal roles in this policy discussion for archivists is putting the cart before the horse, and I would argue similarly regarding publishers on both sides of the argument (besides questions of feasibility and how would publishers and archivists respond economically to certain changes–these are of course important data points). Finally, it seems unwise to intentionally disrupt one of the fundamental bases for scientific communication without a well-functioning alternate in place that is accepted by the scientific community. Developing such an alternate as a pilot project might be reasonable, and if the scientific community organically shifts to embrace it, then wonderful. One sees such a shift in the increasing use of preprint servers (and the increasing acceptance of preprint servers even by traditional journals).

LikeLike

Pingback: What’s ‘unethical’ about Plan S? | jbrittholbrook

Pingback: Luci e ombre di Plan S, la via europea all’accesso aperto | ROARS

It’s interesting, isn’t it, that it is the funder who’s the bad guy here for (quite understandably) wanting the research they fund to be made available under the most open licence so that it can be as widely disseminated and re-used as possible. Is it not the publisher who is restricting academic freedom by refusing to permit such an open license? It takes two to tango. A quite bizarre case of Stockholm Syndrome.

LikeLike

Pingback: What we read this week (21 September 2018) – BMJ Digital