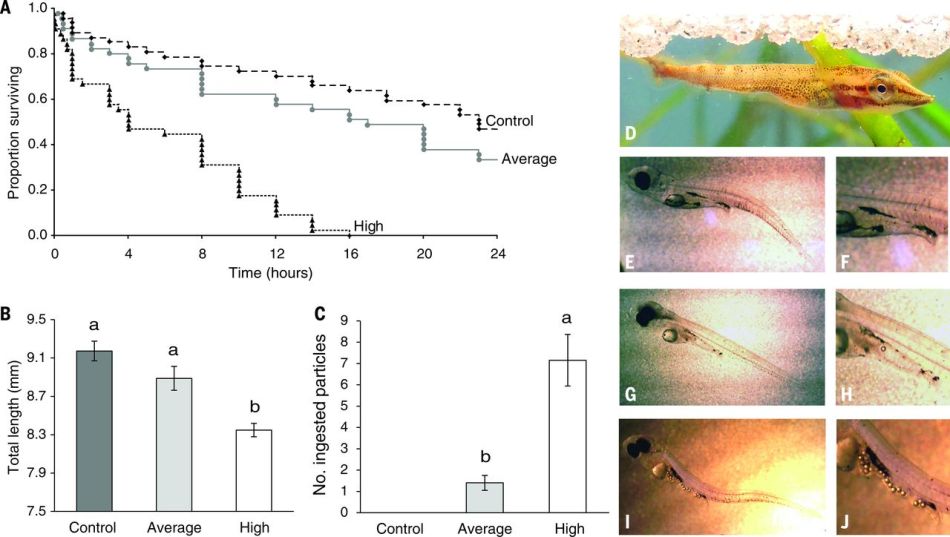

Sweden and the international research community recently faced yet another research misconduct scandal. It was about a Science paper by Oona Lönnstedt and Peter Eklöv, which in 2016 made worldwide headlines with its findings that young fish larvae (or fry), namely Eurasian perch, would eat up plastic pollution like teenagers eat fast food. It soon turned out the research was apparently never performed as described, the original data was missing (allegedly stored only on a laptop, which was then stolen from a car), the results likely made up. The Lönnstedt & Eklöv 2016 paper received an editorial expression of concern in December 2016 and was eventually retracted on May 26th 2017 following misconduct findings by the Swedish Central Ethics Review Board (CEPN), while the two Swedish whistleblowers Josefin Sundin and Fredrik Jutfelt, initially themselves stiffly criticised by the University of Uppsala, were finally exonerated (see panel verdict here and here, further documents here and here). I also make available here the original report by the whistleblowers to the University of Uppsala and CEPN, detailing their “Key points highlighting scientific misconduct by Lönnstedt and Eklöv”. For further reference, read Martin Enserink’s reporting for Science here, here and here.

However, there was more to that Science paper than fraudulent science. Even if the results were not made up, their objective scientific value would still be very questionable, because it had very little connection to the reality of the plastic pollution in the oceans and the fish feeding behavior. The uniformly small, freshly industrially synthesized plastic balls which were fed to the fishes were not really representative of the actual plastic particles polluting our seas. But even those arbitrary chosen particles were not likely to have been eaten by the fishes voluntarily. If the fishes ever did swallow those, it was probably because they were simply made to, being at the point of death by starvation, something which rarely ever happens to actual plankton-feeding fishes in the sea. Of course one cannot expect peer reviewers to spot misconduct and data manipulation, but objectively assessing scientific methodology, result and conclusions of a manuscript is actually what the peer review is all about. One does wonder why the “highly qualified, dedicated” reviewers at Science failed to notice all these obvious scientific shortcomings, and instead decided that Lönnstedt & Eklöv work belonged indeed to “the very best in scientific research”. Was it because the socially and ecologically relevant conclusions sounded so important and welcome, that one simply had to blindly ignore the poor science behind them?

One also wonders even more why the former Editor-in-Chief of Science (and now NAS president), Marcia McNutt, utterly dismissed the concerns of Ted Held, AAAS member, retired plastic industrial chemist of nearly 20 years and aquarium enthusiast of 60 years. Two other critics were invited to submit their brief eLetters, where concerns similar to those by Held were raised. Yet the authors of the two published eLetters, Alastair Grant, professor of ecology at University of East Anglia, UK, and James Armitage, research associate at University of Toronto Scarborough, Canada, were academics, thus proper peers. Which the citizen scientist Mr Held is not. Does it automatically invalidate everything he has to say? Does citizen science count for nothing in academia? Are amateur scientists expected only to unquestioningly applaud and assist their academic role models, while keeping their scientific criticisms to themselves?

Regular readers of my site might recall this is not the first scandal of a citizen scientist being dismissed by the academics, in that other case she was abused and insulted in the vilest of manners by a professor. Ted Held was obviously much luckier in this regard. It is also not the first case of data fabrication at the University of Uppsala, where senior researchers Irene and Kenneth Söderhäll were absolved of all responsibility for the fraud which happened in their lab (see this guest post). And it is not the first questionable decision of the former Science EiC McNutt, who previously decided against the university’s recommendation to retract a blatantly manipulated paper by the notorious plant scientist Olivier Voinnet, in a weird strategically move to issue an Erratum. The new Science editor, Jeremy Berg, indicated to me that the communication between Held and McNutt, presented below, is “historically” accurate.

Following is the guest post by Ted Held, slightly edited for brevity by myself.

Oona Lönnstedt’s bad science and the failure of Science Magazine, by Ted Held

To some of us who have been attentive to the article by Oona Lönnstedt and Peter Eklöv entitled “Environmentally relevant concentrations of microplastic particles influence larval fish ecology” published in the 3 June, 2016 issue of Science magazine, the recent revelations have only increased our doubts about the vetting process for papers appearing in that magazine.

What may be even more curious is how the latest review of the event in Science (published in the 3-24-17 issue) seems to skip questions of scientific importance, concentrating instead, almost exclusively, on malfeasance of the authors and the academic world surrounding Uppsala University. As far as the 3-24-17 piece goes, the revelations are fascinating. But what will be discussed here are the read-between-the-lines issues in the 3-24-17 piece and earlier questions raised by me that seemingly passed by the review process at Science.

Part I – A brief review of “Fishy Business”

Martin Enserink wrote in Science on March 3rd 2017:

“A group of five aquatic ecologists and physiologists elsewhere in the world has helped Sundin and Jutfelt [the accusers] sort through a mounting pile of evidence and make their case that the work was fraudulent. But Lönnstedt and Eklöv have denied any wrongdoing.

Last August, a panel charged by UU [Uppsala University, -TH] to conduct a preliminary inquiry dismissed the charges [of wrongdoing, -TH] and suggested that Sundin, Jutfelt, and their colleagues had unfairly maligned Lönnstedt and Eklöv”.

A most curious conclusion, given the other evidence in this article. This itself deserves investigation of vetting at UU.

“The term [microplastics] refers to plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters, which include the “microbeads” in skin scrubs and plastic detritus broken down by mechanical forces, sunlight, and weather”.

However, as the article quite explicitly outlines, the sizes actually investigated were those tiny enough to be ingested by the fry, while the “less than 5 millimeter” measure was used in order to make the threat appear significantly higher since the range of particles tabulated, according to their own sources, did not break out sizes in the range ingestible by the fishes. Had that been quantified, the amounts would be significantly lower than the ones quoted in the article. There is a big physical difference between 5 millimeters and 0.09 millimeters. Further, the particles they said they used were obviously nice and uniform (see the pictures in original article), certainly freshly manufactured, and not naturally-occurring, weathered bits. The critical reader suspects that they were fresh “skin scrub” beads, but that would mean they were not weathered as they would be in nature. Also, the pieces were not broken bits from larger plastic objects.

“In their Science paper, Lönnstedt and Eklöv claimed that European perch larvae – which are more vulnerable to pollution than adult fish – prefer to eat 0.09-millimeter polystyrene beads over a standard food, tiny Artemia brine shrimp”.

This is improbable, likely very improbable, since fishes are quite discriminatory in their food preferences and quite able to reject unpalatable particles unless, perhaps, they were literally on the point of starvation. How the fish were maintained and fed was not discussed by Lönnstedt. Maybe they were on the point of starvation. Chelsea Rochman (University of Toronto, and the Science reviewer who wrote the introductory commentary “praising the work’s policy relevance”) was impressed. This is probably a case of political bias since any serious scientist should have sniffed out the bad science in the Lönnstedt piece. We (scientists included) tend to like what we agree with, even if it is fraudulent. This is a fundamental point for fraudsters. “Tell ‘em what they wish to hear and you’re half way there.”

“Five months after the study was published, Lönnstedt received a $330,000 grant for “future research leaders” from Formas, a Swedish funding agency, for her work on microplastics.

Makes one wonder about vetting at Formas. And it might be noted that the apparent fraud was a success. Some scientists think the whole purpose of science is getting the grant money. Now, Sundin’s suspicions were raised because of the apparent lack of research facilities and other physical problems, not the science.

“Whistleblowing is risky, it can affect your future employability,” he [Timothy Clark, University of Tasmania in Hobart, one of whistleblowers’ supporters, -LS] says – a special risk for Sundin, who doesn’t yet have a permanent job”.

I know from personal experience that pointing out scientific problems risks employment consequences. But legitimate whistleblowing should be praised by scientists and potential bad effects on one’s finances should not enter into the deliberation of when to express concern. Groupthink raises its head. The whistleblowers here are also concerned about microplastics, which may have contributed to their hesitations:

“The group also worried that attacking the study might suggest they aren’t concerned about microplastics. They are, very much”.

See how opinion flavors outlooks? Ideological bias and preconceptions are there, even when there is scepticism. And the possibility of frowns from people worried about microplastics gave them pause, even though they had concerns. This is Groupthink all the way.

“On June 16, 2016, the researchers sent the authors 20 questions about the Science paper. Four days later, they also asked the university to launch a preliminary investigation. The timeline was a central issue …“

The article later says that Lönnstedt answered the group’s 20 questions. But, again, there is no hint at what these questions or answers might have been except for the rather trivial ones of the number of aquaria (beakers, not aquaria) or where Lönnstedt obtained the larvae. As an aside, another question of scientific design concerns using those beakers. Anyone with experience with keeping and raising fish in aquaria would have been highly skeptical of those 1-liter beakers (or whatever their sizes) offering any scientific integrity to the study of the life span or habits of newly-hatched fishes. How was the uniformity and freshness of the water maintained? How was the temperature controlled so as to mimic what the fry might experience in the wild? How did the apparent absence of any natural flora and fauna (plankton) affect their eating habits or their overall health? What was the feeding routine (that is, were the fishes offered actual food to eat or just microplastics)? How densely were the subject fishes kept in those “aquaria”? Were the beakers exposed to natural sunlight? Was the water given any motion (such as with an air stone) in order to simulate natural water currents? There are many other questions about those containers that cast doubt on the science.

“Roche [Dominique Roche, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, another supporter of the whistleblowers, -LS] says journals should also serve as a safeguard. The suspect paper might not have been published if Science had first checked whether Lönnstedt and Eklöv had posted their data, he says. […] He [Science Deputy Editor Andrew Sugden] acknowledges that the data omission slipped through. But Science, which follows misconduct guidelines set by the Committee on Publication Ethics, has no choice but to rely on institutional investigations, he says; “We’re simply not geared up to do that. We’re not investigators.”

Does Science not have a review process before a paper is published? That’s where the scientific questions come in. One cannot condemn any Science reader/reviewer for failing to know about all the actions described in the 3-24-17 article because they almost certainly would have been unaware of all the problems cited there. But they should have questioned several obvious scientific shortcomings.

Part II – Questions to Lönnstedt & Eklöv, and to Science magazine

As mentioned previously, any reviewer at Science magazine would not have had access to any of the evidently fraudulent practices cited in the “Fishy Business” article from 3-24-17. Neither would the typical reader of Science. In simply reading a research paper published by a reputable source, one assumes that, first, it was not written for purposes of fraud, and second, that it has been reviewed by competent reviewers before publication. The most important point is the second. We readers rely on the publishers to weed out fraud. This paper by Lönnstedt and Eklöv apparently sneaked through the vetting process, that process consisting of at least two layers of scrutiny.

As I read the original Lönnstedt article, several questions occurred to me. This is not unusual as I am a sort of skeptical person, and this particular article overlapped some areas of my own expertise. I e-mailed Dr. Lönnstedt with five questions, these being the most obvious to me at the time. The e-mail was sent on 6-20-16. Here are my five questions.

- Your reports of the concentrations of plastic particle pollution have an odd designation of particle per cubic meter. My understanding of plastics is that most are lighter than fresh water or sea water. Therefore, stating the concentration as a function of volume seems wrong. How would your particle counts differ if the counts were taken between 1 and 2 meters below the surface rather than the top meter? I have attached here [and attached to this missive e-mail as well] an article from the American Society of Plastics Engineers (SPE) which includes numbers stated in surface terms (particles per square meter) which seems much more appropriate. I know that certain plastics contain “fillers” that make them denser. But if they are denser than, for example, a specific gravity greater than 1.035 they will tend to settle to the bottom rather than be suspended in the water column. Perhaps you could be more precise in your description of the extent of pollution and how it is distributed. My estimate is that plastics tend to form a floating layer.

- Your article fails to give a particle size distribution for the particles that are currently present in nature. You say that what is relevant as pollutants are particles smaller than a 5mm dimension. But then your experiment uses the artificial (and arbitrary) size of 90 microns. What fraction of the overall pollution is represented by 90 micron particles? This obviously bears on whether or not your experiment is “environmentally relevant.” In the case of the Pacific Ocean data outlined in the SPE paper the fraction of Pacific particles from 1.0mm to 4.749 mm is 55% by count and 72% by weight.

- How did you obtain your set of 90 micron particles? Looking at the picture of the fish with particles trapped in their gut suggests that these particles are spherical, smooth, rather uniform in size, and (probably) manufactured and kept before use in an artificial setting. If my inferences are correct, your experiment deals with essentially “fresh” particles and not broken fragments as might be found naturally. These may not be appropriate if, for example, there are residual monomers or other leachable chemicals present. Natural plastic pollutants would probably be “weathered” to a large degree, meaning that more volatile and/or soluble components would have been lost to the sea and diluted or evaporated into the sky. It was not stated whether or not you tested for chemicals leached into your test containers. Perhaps your results reflect these sorts of pollutants and not plastics per se. Why not just capture some ocean particles and test those? That would seem to bear more directly on any adverse effects of plastic pollutants.

- It is certainly curious that you selected a 90 micron particle size. Because of this, the fish seem to have been easily able to ingest them. Had you used particles of a different size (say 1 mm) ingestion could not have occurred. As a consequence, bad effects from ingestion are likely due to the particle size and probably distort any natural effects in the sea.

- Another factor regarding your particles that probably distorts the results is that the experimental pieces seem to be both spherical and smooth. Since fish generally have screening powers in their mouths and tend to reject (spit out) things that do not seem edible before swallowing, having smooth, round, small particles will tend to increase ingestion causing or contributing to bad effects resulting from that. If, for example, you had hard-fractured 1 mm particles my bet would be that there would be fewer ingested pieces. An analogy would be human children playing with toy pieces the size of grapes. That could result in a choking hazard. If that same child were playing with a soccer ball, the choking hazard would not exist.

My end comment to her in the 6-20-16 e-mail was “I’ll end this here since I think I’ve made my points. My summary is that your experiments, even assuming that your data-taking is accurate, probably do not have much (or, maybe even any) association with being “environmentally relevant” to the subject of plastics pollution.” I waited for Dr Lönnstedt’s response. I never received one.

I did send another e-mail a couple of minutes later to the then-editor of Science magazine [Marcia McNutt, -LS], who had been cc’d on the original e-mail to Dr. Lönnstedt. I quickly got back a short note from her:

“I am certain that Dr. Lönnstedt will have no problem responding to your queries. These issues are all well addressed in the environmental literature”.

Are they really? Let’s see. . . That the plastic particle distribution in the ocean might be influenced by the various densities of plastic refuse has been discussed in the “environmental literature”? How about a reference? That the article I attached [Eriksen et al, Plastics Engineering 2013, -LS] used the more credible figure of particles per square meter might have been a hint that the Lönnstedt article may have been incorrect. Of course, the Society of Plastics Engineers (SPE) is an industry grouping, not a publisher of “environmental literature.” Nevertheless, it seems as though they (the SPE) had enough sense to realize that most of the problem is plastics that float and that those pieces and particles are concentrated in the upper layers of the water. Next, we have the issue of those 90 micron bits that Dr. Lönnstedt uses as a surrogate for plastic pollution being “environmentally relevant.” Without any reference as to the proportion of existing plastic pollution in the 90 micron range, the issue of “environmental relevance” is moot. Maybe a reference from The Science editor? None. But we may suppose that the issue is “well addressed” somewhere or another. Or maybe our next item: Where did Dr. Lönnstedt get the nice, smooth, and very uniformly-sized 90 micron particles? Maybe this issue has been “well addressed in the environmental literature.” But my guess is that it has not been addressed, there or anywhere else. Finally, there is the curiosity of using only particles small enough to be ingested by the target fish fry. It is doubtful that this issue has been “well addressed” in any literature, environmental or otherwise.

So, what of the response from the editor? Was she completely fooled by Dr. Lönnstedt? Or was she simply being dismissive of honest questions being posed by an AAAS member? Was she actually familiar with the discussions in the “environmental literature” or was she just bluffing?

One imagines that an editor of a magazine like Science would be part of a mechanism to field questions from readers. Rather than sending off a chippy little response to reader queries, one would think that the editor would have passed the note on to a person or panel of persons whose duty it was to think about and perhaps act on skeptical comments about any article. If the comments are wrong or kooky, then that person or panels of persons would respond appropriately. On the other hand, if serious issues are raised, it would be incumbent on them to take appropriate action, up to and including recommending a formal review. Evidently, either this kind of review mechanism does not exist at Science magazine or the then-editor did not bother to use the appropriate pathway.

As I mentioned previously, no one cannot be faulted for not knowing of the alleged problems cited in the 3-24-17 “Fishy Business” article. How can one know these things without intimate scrutiny of every author? There is no hint of that sort of malfeasance in the article’s text. But Science can be faulted for not having proper vetting of the article in question before publication.

Jeremy Berg, Science‘s new editor-in-chief, allowed me to quote him with this email he sent Held on June 12th 2017:

“Dear Dr. Held: Thanks for your note. Let me address some of the issues that you raise.

As is the case for all of our papers, this submission was reviewed by members of our Board of Reviewing Editors and then by outside reviewers with more focused expertise in the area. The reviewers were quite supportive of the paper although they did raise concerns, many of which were addressed during the revision of the submission. Such peer review processes are certainly not perfect, but are made in good faith with the goal of finding reviewers with appropriate expertise who are capable of finding flaws in the submitted materials and in appreciating the potential importance of any findings. There is no reason to assume that there are any other motivations that led to the publication of this paper.

We do take responsibility for the processes that led to the acceptance of this or any other paper. One concrete issue is the lack of available data. We are working on refining our processes to endure that data that are supposed to be available are, in fact, in place and available”.

Donate!

If you are interested to support my work, you can leave here a small tip of $5. Or several of small tips, just increase the amount as you like (2x=€10; 5x=€25). Your generous patronage of my journalism will be most appreciated!

€5.00

Top journals publish a lot of nonsense which is not really fresh news and reviewing simply does not work for many big names. I heard of stories told by postdocs from famous group that their prof calls to editors before submitting papers to make sure it goes to right reviewers. Looking at some Science papers there is certain feeling that nobody including editors even tries to read them before acceptance. Unfortunately it is not problem of Science but rather general trend for many high profile journals. The main criteria for acceptance of paper is expected number of citations. These are commercial organizations which generate profit and compete with each other. Well, one additional reason for publication of nonsense was spotted by Leonid in his previous article: very often the top journals get reviews not from professors but from their grads or postdocs. These guys may simply overview a lot of nonsense due to lack of experience or too strong trusts to reputations of famous names.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on CraigM350.

LikeLike

Scientific production must be reformulated from the scratch. Don’t know how. But this nonsense of mofos getting grants by publishing non reproducible result b.s. on high impact factor b.s. journals has to stop!

LikeLike

Unfortunately the paradigm of the last 30 years has been unfortunately the equation: unreproducible data:high impact journals:grants

However with the appearance of journals with no impact factor, open access to original data and pub peer as well as leonid ‘s site this paradigm may soon change….

LikeLike

Cf.

http://Web.Archive.org/web/20121212173007/http://www.habitoflies.co.uk:80/pg_apx2.htm#NN

(correspondence with “Science”) of “A Habit of Lies: How Scientists Cheat” by Dr. John Alexander Hewitt.

Regards,

Colin Paul de Gloucester

LikeLike

Pingback: Science misconduct – For Better Science