The Lancet, an elite medical journal published by Elsevier, is responsible for a number of controversial publications, on which its Editor-in-Chief Richard Horton and his editorial office have not always acted to everyone’s satisfaction.

The Lancet and the magic of stem cells

The probably biggest Lancet scandal now is that of the trachea transplant surgeon Paolo Macchiarini, the sacked professor at the Swedish Karolinska Institutet (KI). His most prominent critic, Belgian thoracic surgeon Pierre Delaere has publicly called on my site for a retraction of all four of Macchiarini’s paper in The Lancet (Macchiarini et al. 2008, Jungebluth et al. 2011, Badylak et al 2012, Gonfiotti et al. 2014); also the Swedish Academy of Sciences asked the journal to act on Macchiarini’s papers. Elsewhere, Italian media provided evidence that the Gonfiotti et al. 2014 case report paper “The first tissue-engineered airway transplantation: 5-year follow-up results” misrepresented the true medical condition of Macchiarini’s first stem –cell regenerated trachea recipient. Corriere Fiorentino reported in February 2016:

“Patient 1, operated in 2008 in Barcelona. Doing well, according to [the paper’s authors] Macchiarini, Gonfiotti and Jaus. Minor complications, the patient ‘leads a regular life’. Yet, at Careggi [Florentine hospital, where Macchiarini used to operate, and where he is accused of committing extortion, -LS], between 2010 and 2012 he was re-operated eleven times, and the second report reveals that, between 2009 and 2011, he was rushed to surgery to seven times, with ‘no definitive resolution”.

To me, Seil Collins, media relations manager for The Lancet journals, stated in this regard:

“There are a number of enquiries related to the Macchiarini case, including the investigation into scientific misconduct which was re-opened and an external investigation into KI’s handling of the case. We will respond to the findings of the current investigations once they have reached a verdict”.

At the same time, the rather questionable Lancet editorial from 2015, issued after the now-retired KI leadership had dismissed the findings of Macchiarini’s misconduct, remains proudly standing. In it, the EiC Horton slammed Bengt Gerdin investigation as

“a flawed initial inquiry completed by a single individual with widely disseminated, damaging, and mistaken findings […]. Dragging the professional reputation of a scientist through the gutter of bad publicity before a final outcome of any investigation had been reached was indefensible”.

All that The Lancet was inclined do so far, was to issue an Expression of Concern for the Jungebluth et al. 2011 paper and remove first one, than another three authors, according to their expressed requests. In this regard it is not clear what the editorial rationale for authors’ removal was. The Lancet is member of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), which stipulates that all authors are “to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved”. There is no small-print clause like “until they decide otherwise”. Therefore, unless these four authorships were originally awarded undeservedly, such author removal might in fact contradict the rules of editorial ethics which The Lancet has subscribed to.

Update: The Lancet did retract a paper by Macchiarini about plastic trachea (Jungebluth et al. 2011), upon fraud findings and request from Karolinska. The journal however refused to act on Macchiarini’s cadaveric trachea papers Macchiarini et al. 2008 and Gonfiotti et al. 2014, on advice from COPE.

One of the ex-authors of the Jungebluth et al paper in The Lancet, the clinical immunologist Katarina Le Blanc, has now been, according to my information, accused of misconduct and data manipulation as well. The Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter reported:

“The actual research was about a health care method for critically ill patients. It was about a survey of treatments and therefore included patients from several hospitals in the world. The therapy worked very well in slightly more than half of the patients, for some it worked partially and for some not at all. Yet two of the Swedish patients in the study recovered and showed no signs of disease before receiving the treatment. Despite this, they were counted in the group that got well. That this was done intentionally is not in doubt. The suspected research fraud has not been flagged earlier because of fear of reprisals, but an anonymous report will be submitted to the President of Karolinska Institutet”.

I received confirmation that the scientist in question was indeed Le Blanc from a reader of my site quoting “an initiated source”. The paper in question is, according to available circumstantial evidence, also in The Lancet, namely Le Blanc et al, 2008. Update: Le Blanc turned out to be a whistleblower, who actually reported that same case misconduct case she was investigated for.

There are currently other papers The Lancet should be paying attention to, instead of passively waiting for the outcome of institutional investigations as Collins announced. Some of those publications deal with Macchiarini-style regenerative medicine.

A Lancet paper by former Macchiarini collaborators Martin Birchall, as well as Alexander Seifalian and Augustinus Bader was criticized by Delaere for suppressing certain crucial information in order to present their scientifically shaky role of stem cells in trachea regeneration as a success (Elliot et al,2012). The investigative committee at UCL apparently thought that the omission of the life-saving “stent and surrounding vascularised omentum tissue wrap” was only a minor aspect of the otherwise scientifically solid Lancet paper. Read more about this paper here.

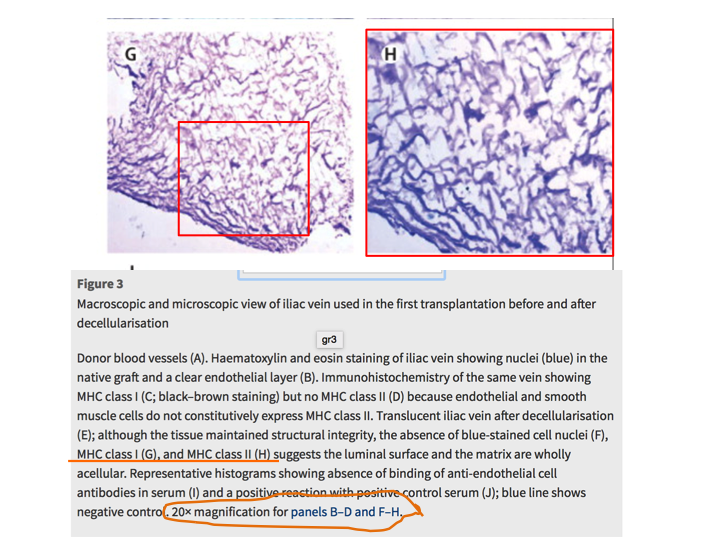

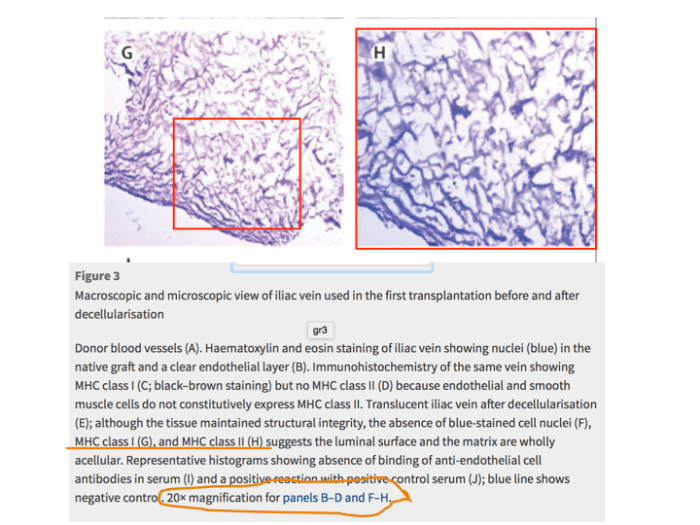

One recently discovered image duplication in a Lancet paper by a certain regenerative medicine specialist should have set off all the alarms: the author was Suchitra Sumitran-Holgersson. I have previously extensively reported on her misconduct and how it was officially covered-up by Swedish authorities, while her investigators were threatened. Afterwards, Sumitran-Holgersson was showered in state and charity funding for her regenerative medicine research on human patients (one of which involved a Macchiarini-style regenerated trachea, with apparently lethal outcome for an elderly patient).

Meanwhile, an internal investigative commission at University of Gothenburg is also looking into her research on vein regeneration from blood cells. These experiments on children patients were published also in The Lancet (Olausson et al, 2012). This is what PubPeer readers found in this paper:

Yet Collins chose to simply ignore my specific inquiry in regard to this Sumitran-Holgersson’s paper in The Lancet.

Update: Sumitran-Holgersson was found guilty of research misconduct and ethics breach.

The Lancet and data sharing

Another issue The Lancet should look into is the so-called PACE trial (which I previously reported on), published in 2011 (White et al). This clinical trial dealt with medical efficiency of different therapies for chronic fatigue syndrome/ myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME, well explained in this recent Guardian article). Just as the aforementioned Le Blanc’s Lancet paper, also the PACE trial apparently passed off patients, who were not sufficiently ill to begin with, as recovered to demonstrate the efficiency of exercise therapy. This, if true, is no minor thing, but puts the integrity and validity of the entire study in doubt.

According to an open letter to the EiC Horton by six critical scientists, PACE trial was based on:

“an analysis in which the outcome thresholds for being ‘within the normal range’ on the two primary measures of fatigue and physical function demonstrated worse health than the criteria for entry, which already indicated serious disability. In fact, 13 percent of the study participants were already “within the normal range” on one or both outcome measures at baseline, but the investigators did not disclose this salient fact in the Lancet paper. In an accompanying Lancet commentary, colleagues of the PACE team defined participants who met these expansive ‘normal ranges’ as having achieved a ‘strict criterion for recovery’”.

Since there were also a number of other heavy concerns about the PACE trial’s set-up, an independent re-analysis of data could surely bring light into the controversy. Yet the authors of this Lancet publication (and a follow-up paper in PLOS One) steadily refuse to share the anonymised patient data (with non-collaborators, that is), citing various reasons. The courts are about to decide on the matter of data release soon.

CFS/ME is not a kind of hysteria it was thought to be, but apparently a very complex and severe clinical phenotype covering a wide range of physiological and psychological disease origins. Yet it is quite clear where Dr. Horton stands: he staunchly defended the PACE trial paper in a radio interview in 2011, insisting that “it’s been through endless rounds of peer review and ethical review” and that “the criticisms about this study are a mirage”. The journalist David Tuller, who was investigating the PACE trial controversy from the beginning, commented to me:

“The Lancet has not explained how this piece of nonsense could possibly pass peer review. It has not even acknowledged that it published a paper with outcome thresholds lower than entry criteria, so that you could be simultaneously “within normal range”–one of the study’s measures for improvement–and disabled enough to qualify the study. That is not hidden or tucked away! It right there in the study. It should have been noticed by anyone who read the study carefully. For a paper to include this analysis is absurd. For a journal to publish it and then not acknowledge such a fundamental flaw after it has been pointed out repeatedly, including in correspondence in the journal itself, is also absurd”.

The Lancet and ‘dangers’ of vaccinations

And then of course there was the Andrew Wakefield scandal. In his 1998 Lancet paper, the former gastroenterologist Wakefield raised a claim that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine would cause autism and bowel disorder in children. This paper was soon utterly debunked, and turned out to contain massively manipulated data. Yet it took The Lancet whole 12 years to retract it. The tremendous damage to public health however was long since done; in fact Wakefield was and still is quite successful in retaining his credibility with celebrities and the growing anti-vaccination movement, portraying himself as a victim of conspiracy. Also due to The Lancet’s authority, our society currently faces the return of measles and other deadly epidemic diseases, simply because too many parents are afraid to vaccinate their children.

Wakefield’s autism-by-MMR-vaccine paper was eventually retracted in 2010, and Wakefield himself lost his license to practice medicine. It seems, The Lancet retracted the paper not entirely from their own accord, but “following the judgment of the UK General Medical Council’s Fitness to Practise Panel”. The journalist Brian Deer reported in The BMJ how Wakefield and his paper were incessantly supported by The Lancet’s EiC Horton. In his 2011 feature story, “The Lancet’s two days to bury bad news” Deer told about his meeting with The Lancet editors, Wakefield and his two collaborators Simon Murch and John Walker-Smith:

“Mostly I had stood, occasionally pulling documents, as Horton, with five editors, took notes. I told them that the paper’s first author, Wakefield, was retained by a lawyer and was funded to help sue vaccine manufacturers. Admissions criteria for the study had been manipulated and ethical safeguards flouted. A group of developmentally challenged children of parents who blamed MMR had been brought to the hospital to create a case against the vaccine. I said I thought that the study was ‘rigged’”.

What happened then? Straight after this meeting, Horton issued an editorial, where he defended Wakefield and Co outright, stating that “allegations of alleged research misconduct have been answered by clarifications provided by the senior authors of this work”. Horton’s editorial was followed by Murch’s, Walker-Smith’s and Wakefield’s statements, as well as a statement by the Royal Free Hospital which cleared Wakefield and Co from suspicions of misconduct in their internal investigation. Actually, the accused doctors had been investigating themselves. This Horton actually was perfectly well aware of, and did not at all mind, as Deer found out. The fact that the hepatologist Horton used to be a former colleague of Wakefield, Murch and Walker-Smith’s at this very London-based hospital, in fact “on the same corridor”, may or may not have influenced his decision to support them. In any case, neither Horton’s ill-informed editorial nor his former ex-colleagues’ statements have been retracted so far. Every anti-vaxxer can read those and use them as proof that Wakefield was right and the “truth” about dangers of vaccines is being suppressed. Therefore, one has to ask: does this actually bother Dr. Horton and The Lancet at all?

In 2003, Horton stated in his book: “I do not regret publishing the original Wakefield paper” because “progress in medicine depends on the free expression of new ideas”. He again defended this publication in a Guardian article in 2004: “There has been more nonsense written about Wakefield’s 1998 Lancet paper than almost any other study in my memory”. Wikipedia has another example for Horton’s unorthodox attitude to new ideas: in 1996 his expressed some support for the theories of AIDS denialist Peter Duesberg and insisted that AIDS cannot be exclusively caused by HIV.

Therefore, does the medical journal The Lancet actually care about patients?

Other Elsevier journals, especially Cell, also have a questionable tradition of ignoring suspicions of data manipulation. Is this therefore a specific Elsevier thing of only acting on a problematic paper when the outside pressure becomes too high? It seems, The Lancet has so far happily relied on institutional decisions, at Stockholm and London, regardless of the otherwise available evidence and of how corrupt or biased these investigations were. Whether the papers in question are medically or scientifically reliable, was for The Lancet so far seemingly beside the point, as Collins’ reply to me indicated.

In any case, one should not forget that manipulated data in The Lancet has much more disastrous and potentially deadly consequences than anything published in the basic life science journal Cell. In the latter, it is mostly about damage to science and waste of public resources (though, once clinicians like Macchiarini start to base their patient treatments of unreliable or fake basic research, people are likely to start dying as well). Yet with The Lancet, everything published there immediately becomes gold standard for human medicine. We saw the result with Wakefield, and we also see that the trachea regeneration method a la Macchiarini is about to be applied on patients once again. With millions of Euros in EU funding, simply because it was published in The Lancet.

The article was updated on 1.12.2019

Donate!

If you are interested to support my work, you can leave here a small tip of $5. Or several of small tips, just increase the amount as you like (2x=€10; 5x=€25). Your generous patronage of my journalism, however small it appears to you, will greatly help me with my legal costs.

€5.00

There is a small error regarding the PACE trial. The article states that patients enrolled in the trial were not sufficiently ill to begin with. I don’t think this is in question. There are some question on how representative the selected patients were but that is ultimately not that important because there are far bigger problems.

As you wrote, patients were passed off as recovered when they were still ill. On the six minute walking test, the best results were a mean distance of 379 metres in the GET group, an improvement of 67 metres in 52 weeks. This is worse than patients listed for lung transplantation and older patients with chronic heart failure. http://www.meassociation.org.uk/2013/07/pace-trial-letters-and-reply-journal-of-psychological-medicine-august-2013/

The PACE trial also had many design flaws that ensured the results would be misleading. Sense About Statistics published an article on this last month:

http://www.stats.org/pace-research-sparked-patient-rebellion-challenged-medicine/

LikeLiked by 1 person

“On the six minute walking test, the best results were a mean distance of 379 metres in the GET group, an improvement of 67 metres in 52 weeks.”

All arms in the PACE trial received standard Specialised Medical Care (SMC), with one arm receiving SMC only.

The four trial arms were: SMC only, APT + SMC, CBT + SMC, and GET + SMC.

So the 67 metres result for the GET arm (at 52 weeks) is the combined distance for GET + SMC.

Subtracting the SMC only result from the GET arm result leaves a net gain of just over 35 metres that could be attributed to GET itself. This result is statistically significant, but not clinically significant, a much more important and relevant standard

Patients were also coming off an extremely low baseline, so this minimal gain (after a full year of therapeutic intervention) is practically meaningless, and leaves patients – as you noted – still scoring down with some of the most disabling and serious diseases on the books.

Then the 2.5 year follow-up study published in late 2015 showed no difference between all four trial arms on the two primary outcome measures (both subjective self-report).

(It is worth noting that the 6-minute-walk-test was the only objective measure on which PACE scored a positive result, and it was only for the GET arm, and only at 52 weeks – no objective measure was used at 2.5 years.)

Even leaving aside the multiple serious methodological problems with PACE, by its own standards it has delivered a clear null result for CBT and GET.

LikeLike

Is it that the patients were too well to be ill, or too ill to be ‘recovered’? I’d think that there was more of a problem with the criteria for ‘recovery’ than entry, but either way, the Lancet shouldn’t have been claiming patients fulfilled a ‘strict criterion for recovery’ when they could have been reporting worse symptoms than when they started the trial.

LikeLike

If a paper is retracted, it is really important that the COPE rules are adhered to. COPE state in their retraction guidelines (http://publicationethics.org/files/retraction%20guidelines.pdf) that “retracted articles should not be removed from … electronic archives but their retracted status should be indicated as clearly as possible.” Myths about what an article said or didn’t say can be tricky to squash if the papers are difficult to access. Horton is in fact correct when he says “There has been more nonsense written about Wakefield’s 1998 Lancet paper than almost any other study in my memory”. I don’t think he said that to defend the paper’s authors. The Lancet took great pains to make sure that the article explicitly stated there was no link between MMR and autism.

The reason it is important that retracted papers remain in the research archive (albeit labelled as such), is that they are an crucial learning tool and enable future problematic articles to be spotted. When I was studying for my masters, we used the Wakefield paper to illustrate how not to do research.

LikeLike

Horton is a problem. He changed track to journalism very early in his medical career. Is there any sign of scientific training since then? His misplaced trust in “endless” rounds of PACE peer and ethics review sounds like a journalist speaking, rather than a scientist.

LikeLike

The Lancet, and BMJ have editorial policies that favour the CBT fanclub. It’s even been tested (by comparing % psych papers with other, similar high impact general medical journals) using statistics. You should all know this by now. both paper son the editorial policies (BMJ and Lancet are online (Axford’s Abode). No need to reinvent the wheel.

LikeLike

Great article. thank you. Just one note on the statement that CFS/ME is “a very complex and severe clinical phenotype covering a wide range of physiological and psychological disease origins.”

PACE used the Oxford definition which only requires 6 months of medically unexplained chronic fatigue, does not require patients to have hallmark criteria of the disease, and allows patients to have primary mental illness. Oxford is little more than unexplained chronic fatigue.

But the 2015 report by the prestigious U.S. Institute of Medicine emphasized that the disease is not a psychological disease, that there is significant evidence of neurological and immunological impairment and that the disease is characterized by a systemic intolerance to activity. A 2015 report by the U.S. National Institute of Health stated that the Oxford definition used in PACE was so broad as to include other conditions than just CFS/ME and therefore called for it to be retired because it could “cause harm.”

So while it is correct to say that CFS/ME as defined by PACE includes a wide range of causes for non-specific chronic fatigue, I dont believe it is true that the disease described by the IOM covers “a wide range of physiological and psychological disease origins.”

The problem is that disparate definitions have been conflated as representing the same patient population when they do not.

LikeLiked by 6 people

Thank you very much for covering the PACE trial in your fascinating piece. That 6-scientist letter to The Lancet is now a 42-scientist letter and still, no retraction of the bizarre analyses in question, with ongoing harm to patients.

http://www.virology.ws/2016/02/10/open-letter-lancet-again/

I genuinely cannot understand why Richard Horton does not act.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Because it’s part of his grand plan.

LikeLike

Which is? Do tell more!

LikeLike

And here’s another demolition of the PACE trial: http://www.sciforschenonline.org/journals/neurology/JNNB-2-124.php A review article entitled ‘The PACE Trial Invalidates the Use of Cognitive Behavioral and Graded Exercise Therapy in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Review’ published a few days ago by the Journal of Nerology and Neurobiology. Well worth a read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Look at ME Research online for the paper on the Lancet http://www.axfordsabode.org.uk/me/melist.htm

Then check out; http://freespace.virgin.net/david.axford/JCFS.pdf

Horton has very right wing tendencies (he’s also very anti-Israel). Yes, political views play a role here. Don’t know about Godlee but she shares the pro-psychiatric bias.

So you can see the wood for the trees and are not diverted to focus on tests that are not even appropriate for this patient population (why are people not listening to those who know like Drs Van Ness and Snell?), http://www.axfordsabode.org.uk/me/ME-PDF/PACE%20trial%20the%20flaws.pdf

It’s like no one in Europe had noticed the issues since 2004 when there were a lot of us who wrote endless papers on the deeply flawed RCTs on CBT and GET (starting with Sharpe et al BMJ 1996. check out the table showing baseline differences between the CBT arm and controls.) Any trial using the Chalder Fatigue Scale is difficult to interpret because it asks patients about their tiredness during the past two weeks, as though they were healthy three weeks ago. ME fluctuates so you need a questionnaire like the PFRS (UK) or De Paul questionnaire (USA).

Also example, the step test etc is fairly meaningless, if you do it once and don’t repeat the next day (to check for the cardinal symptom of post-exertional worsening). Once-off tests are simply rubbish for ME. Even minor differences say nothing. You have to repeat all these tests after 22 hours (when significant differences tend to show up). 24-48 hours is also fine (Paul et al, 1999). That’s the objective test for ME but shhhh, don’t tell the psychiatrists.

Beware of online journals where you have to pay to get things published. Might not be the best, says she who did that as no other journal would publish on progressive ME, even Fatigue. anyway, main message is that all this won’t touch the Lancet. Now, if you could show money changed hands….

LikeLiked by 2 people

Although we should be cautious of some open access journals, J Neurol Neurobiol does at least peer review the papers it receives (http://www.sciforschenonline.org/peer-review.php).

LikeLike

Well, this Dutch GP, who knows me, thought he needed to flag up my typo. Shall we go through his paper and flag up his less-than-perfect English here and there? Honestly.

LikeLike

Actually, he makes some important points but I also noticed a few factual errors. If you criticise others for being less than accurate, you have to check that what you write is accurate. For example, ref 35 is wrong. If you look at the report, you won’t see the authors listed. (Because they didn’t write it.) Makes me wonder what else is not quite right. But definitely thought provoking. (Given he quoted me, he needn’t have flagged up my typo, as being a quote means people know I was responsible and not him. So PWME writes the odd typo. Shoot me! I’ve emailed him.

LikeLike

Pingback: Does the Lancet care about patients? | WAMES (Working for ME in Wales)

For some editors admitting that they are wrong would be an act of self-mutilation.

On Tue, Apr 5, 2016 at 3:25 AM, For Better Science wrote:

> Leonid Schneider posted: “The Lancet, an elite medical journal published > by Elsevier, is responsible for a number of controversial publications, on > which its Editor-in-Chief Richard Horton and his editorial office have not > always acted to everyone’s satisfaction. The Lancet and th” >

LikeLike

Pingback: Frontiers’ bread madness – For Better Science

Pingback: Why the dispute about PACE trial data matters to everyone. – johnthejack

Pingback: The stem cell faith healers, or magic inside your bone marrow – For Better Science

Pingback: Macchiarini and the bonfire of greed – For Better Science

Pingback: My Walles trachea transplant reporting fails peer review – For Better Science

Pingback: Retraction, and another looming misconduct finding for Macchiarini and Jungebluth – For Better Science

Pingback: COPE, the publishers’ Trojan horse, calls to abolish retractions – For Better Science

Pingback: Sumitran-Holgersson and Olausson guilty of misconduct and unethical experiments on children – For Better Science

Pingback: The PubPeer Stars of Weizmann Institute – For Better Science

Pingback: The rise and fall of an antivax paper, by Smut Clyde – For Better Science